Thanks to a visionary botanist, a man-made forest sits in the middle of the Nebraska prairie.

Every lonesome motel in the Nebraska Sandhills is booked solid. It’s mid-November, unseasonably warm, and every outdoorsman in the state with a deer license and a few vacation days is in a field, eager to bag a trophy buck. Out here—the Sandhills are always out here or out there, always out, out—in one of the largest intact grassland ecosystems in North America, the fescue snaps beneath their feet. The grama. The bluestem. The needle and thread grass. The fuel that once marshaled great wildfires across the dunes, across what author Jim Harrison called “without a doubt the most mysterious landscape in the United States,” wiping the slate clean, consuming everything but the sand.

“You begin to doubt your sensibilities,” Harrison wrote. “My feeling for the Sand Hills competes with the magnificent Pacific Ocean. The vastness and waving of the hilly grasslands in the wind make you smell salt.”

Because every lonesome motel in the Nebraska Sandhills is booked solid, the contract crew down from Wisconsin—14 workers, most of them Mexican immigrants—will stay in Broken Bow, the “Gateway to the Sandhills,” instead. They are here to help the Charles E. Bessey Tree Nursery, the nation’s oldest federal tree nursery, lift and pack nearly 800,000 container trees, seedlings raised in individual receptacles rather than in the ground. The nursery’s backdrop is the 20,000-acre Bessey Ranger District, the largest hand-planted forest in the western hemisphere.

At the turn of the 20th century, none of this existed. The Bessey Ranger District was indistinguishable from the miles of so-called “wasteland” surrounding it. But in time, thanks to a revolutionary botanist and his singular devotion to the idea of a forested Sandhills, it has become so established and so engrained in the landscape of central Nebraska its own residents—myself once included—hardly bat an eye at the incongruous trees.

It’s easy, once you’ve crossed the lazy Middle Loup River and entered the nursery gates, to lose perspective out here; to walk through the forested hills behind the nursery, the floor littered with cones and needles, and forget the almost 20,000 square miles of dry, treeless rangeland surrounding you. One quick glance across Highway 2 and you’ll understand the magnitude of the achievement here. Behind, a forest of pine and shadows, green on green. Ahead, brown as far as the eye can see, waves in a sea of prairie grass.

But to drive through the semi-arid Sandhills on Highway 2 and find the Bessey Nursery and Nebraska National Forest is, in some ways, to stumble upon Area 51, a complex tucked deep in the wilderness, a testing ground hidden in the desert, out of sight, out of mind, out of context. It is a man-made anomaly, the final result of what botanist and University of Nebraska professor Charles E. Bessey humbly called a “somewhat prolonged study of the Nebraska Sandhills.”

Over the din of pneumatic staplers and Spanish asides, nursery manager Richard Gilbert calls out to the foreman. “Make sure he gets those tucked in really well, Monty, otherwise it’ll kill the trees.” Once a landscaper and part-time corrections officer, Gilbert now oversees the entire nursery operation: the greenhouses, the 46 acres of irrigated seedbeds, the seed bank, the extraction, the planting, packing, shipping, and more. He’s standing vigil at the far end of a multi-level conveyor belt flanked by workers on both sides, stacks of white Styrofoam seedling containers above and beside them. Bunched together, the seedlings’ bushy, green needles look like rows of fresh sod. One by one, they lift the pines like carrots and send them down the line. Dirt piles up at their feet. Sunlight creeps in through the loading docks. The lights buzz and the vents hum and a pallet slaps the concrete floor. At the end of the line, two men pack the loose trees in clear plastic bags, then into boxes, and then into a freezer, where they’ll lie dormant until they’re ready to ship out in the spring.

“We just let mother nature take care of this,” Gilbert says. “They get them planted. They come out of dormancy. They start growing. It works out really, really slick.”

The Bessey Nursery provides container trees for the entire U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region (South Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado and Nebraska), in addition to the Bureau of Land Management and some Native American tribes. Most are used in reforestation after fires or disease. Today alone they’ll pack 150,000 Ponderosa pines bound for the Black Hills National Forest in South Dakota. In August 2000, what eventually became known as the Jasper Fire ravaged more than 83,000 acres of the forest; a fire so hungry it consumed the equivalent of seven football fields per minute; a fire “so hot,” Gilbert says, “it scorched the earth and nothing came back.” With the help of the Bessey Nursery out here in the Great American Desert, the Black Hills National Forest has been replanting ever since.

Gilbert hesitates to credit global warming—“I’m not an expert on that,” he tells me—but he repeatedly emphasizes the spike in demand for container seedlings over the last decade. The fires are more frequent, the infestation of insects like the bark beetle more severe. The Bessey Nursery sells roughly 1.5 million bare-root trees and shrubs every year to natural resource and conservation districts across the Plains, with the capacity to grow at least 4.5 million at peak production. But it’s the container trees—smaller, easier to plant—that keep it from closing like so many other federal nurseries have since the 1990s due to budget cuts.

“They really looked hard at closing Bessey, and they were going to. If we wouldn’t have put up greenhouses, they would have closed us—guaranteed,” he says. “The oldest federal tree nursery in the U.S. would have been closed, and it would have been a shame.”

By the time Charles Bessey arrived at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 1884, not yet 40 years old, he’d already established himself as a lion in American botany. He was a short, stocky man with broad shoulders and a beard one student described as “long and dichotomous.” Three years earlier, he’d published the seminal textbook, Botany for High Schools and Colleges, pushing the instruction of botany well beyond collection and simple identification, exercises so general he considered it little more than “cheap sentimentalism.” Adopting what his European cohorts had already been practicing for years, Bessey added cells and tissues into the curriculum and stressed evolutionary form and function over static classification. Simply put, he ushered botany into the lab.

“In the history of American botany, Professor Bessey stands for the introduction of a new epoch,” wrote John Coulter for Science in 1915. “If Professor Bessey had made no other contribution to American botany than the publication of this book at the psychological moment, he would have made for himself an enduring place in the history of American Botany.”

The university loved him. They loved his fatherly demeanor, the way he called his students “boys and girls,” the way he gently knocked before entering, the way he warmly said, “come in” when reviewing studies in his cramped and cluttered office. He advocated the microscopic study of plants, what they called “the new botany,” but never belabored scientific minutia; instead, like the bearded sage he was, he often found ways to elevate botany beyond purely scientific concerns.

A generally accepted theory exploded by a single fact!

“Do you realize, my children, that the man whose mind is made up can no longer advance scientifically?” he once told his botanical seminar. “His permanent tissue cannot change. His mind is no longer in a meristem state…Let me admonish you, my children, to be young in spirit. Keep your minds meristematic. Avoid early permanent tissue.” True to his word, Bessey never let pride stand in the way of truth. When a university regent rebutted Bessey’s claim that clover couldn’t be grown in Nebraska with photos of his own healthy 10-acre stand, Bessey perked up. “A generally accepted theory exploded by a single fact!”

Born in a log cabin on his parents’ farm in Milton, Ohio, in 1845, Bessey was home schooled until the outbreak of the Civil War. He attempted to enlist, but they turned him away, too young to fight at just 16. Several years later, he moved to Michigan, where he worked as a surveyor and what they called a “timber cruiser,” taking measurements to estimate the amount of standing wood in a forest. He registered for classes at Michigan State Agricultural College, graduating with a botany degree in 1869. He accepted his first teaching position two years later at Iowa State College, where he introduced his students to the principals of the new botany movement, the first botanical class in North America to utilize a laboratory.

It was during his tenure at Iowa State, at a meeting for the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1872, that Bessey first met celebrated Harvard botanist Asa Gray, considered today the most important botanist of the 19th century. Subsequently, Bessey spent two separate winters studying with Gray in between his teaching responsibilities back on the plains. Hardly a fickle man, he stuck with Iowa until 1884, when Nebraska offered him the first deanship of the College of Agriculture. It would be his second and last professional move, though he was offered many more.

In 1887, Bessey was named to a joint committee between the State Horticultural Society and the State Board of Agriculture, a committee whose goal was to petition the legislature to designate tracts of land in the Sandhills specifically for tree planting. The campaign failed, but once rooted, Bessey couldn’t let go of the idea of a forested Sandhills. “The question naturally comes to us whether it is possible to reforest this area,” he wrote. “That it would be desirable to do so needs no argument.” Cattlemen and homesteaders out west desperately needed the trees, needed the wood for fencing and other chores on the ranch, and should the demand for timber drastically increase nationwide—as many projected it would—the supply would too soon dry up. His early study of the region proved that, despite its reputation as a desert wasteland, the soil was moist below the surface, its sands fixed in place by a cover of mixed prairie grass. Combined with his experience in the pine forests of Michigan, which thrived in similarly sandy soil, Bessey was sure the Sandhills could be made to host a forest again. When Dr. Bernard Fernow, director of the federal Division of Forestry, performed a series of lectures at the university several years later, Bessey pressed him on the matter.

It would prove to be a serendipitous encounter. A German immigrant, Fernow brought the forestry practices of his homeland with him. In 1868, a group of German foresters and soil scientists assembled in Vienna to brainstorm plans for a comprehensive forest research program. The result was a government-run network of forest research stations, a union so effective at culling valuable forestry data it ultimately spawned an international union in the same vain. Appointed head of the Division of Forestry in 1886, Fernow suddenly found himself in a position to incorporate similar experiment stations in the United States. When an enthusiastic Bessey approached him during his presentation at UNL in January 1891, a future collaboration seemed inevitable. Returning to Washington, Fernow wrote Bessey to pledge the Division’s support.

“I should like to start an experiment there in planting Pinus ponderosa. I have a small amount of money that I could devote to such a purpose. I now would like to have your cooperation and suggestions.”

But the Division, still fledgling after a decade of service, could fund little more than the seed. For the experiment to move forward, Bessey would need to source the land and free labor to plant it. Surprisingly, after a frantic search about campus, he found it in his colleague Lawrence Bruner, a professor of entomology. Bruner owned a small acreage on the eastern edge of the Sandhill territory. In the spring of 1891, the seeds were shipped. In addition to the Ponderosa, the Division planted other various conifers—Jack pine, red pine, Scotch pine, Austrian pine, Ponderosa pine, Douglas fir and more—gathered from multiple forests across the country. In total, more than 13,000 trees were planted, and by October 1892, Fernow reported to the secretary of agriculture “that in the Sand-hill region of Nebraska coniferous growth, especially of pines planted closely together, is the proper method and material.” Unfortunately, lacking funds to pursue the experiment any further, the project was abandoned and soon almost completely forgotten.

Ten years later, however, what was now the Bureau of Forestry accidentally re-discovered the area. The pine trees that survived were roughly 18-feet tall, “healthy and thrifty as if grown in their native forest,” said W.L. Hall, the Bureau’s superintendent of tree planting. They sent word to the president of the plantation’s unexpected success, and Gifford Pinchot, now director of the Bureau, threw his weight in earnest behind the reforestation of western Nebraska.

On April 16, 1902, by presidential proclamation, Teddy Roosevelt established the Dismal River and Niobrara forest reserves, more than 200,000 acres in the middle of the Nebraska Sandhills. In 1906, he added another, the North Platte Reserve, and in 1907, all three were combined to create the Nebraska National Forest. It would be the first and only time the government established a forest reserve without a forest.

“Nebraska was originally a well-nigh treeless state. The great bulk of the trees here have been planted by its own people,” Roosevelt proclaimed during a speech in Grand Island, Nebraska, in 1903. “I am glad to say that through the wisdom of your senators and representatives in helping to establish forest reserves in the Sandhills, now the national government will be able to cooperate with your own spirit of private enterprise. What Nebraska has done in tree planting has extended beyond its own limits.”

Not that I knew any of this growing up. I was born and raised in Broken Bow, outdoorsy enough to join the Boy Scouts, social enough to join the 4-H Club. Both of these groups took occasional field trips to Nebraska National Forest. The Scouts camped in tents, the 4-H kids in cabins. About either of these adventures I remember only splashes: the bunk beds, the dance in the mess hall, the poison ivy, and, of course, the Zipline, as much a novelty in central Nebraska as the trees themselves. I remember the still-heat of summer. I remember the scent of cedar and pine.

I’m sure we toured the nursery, but in truth, I don’t remember that; neither do I remember if we were taught about Bessey. Only as an adult have I grown interested in the Nebraska National Forest, a byproduct of my fascination with the Sandhills in general. I’ve since traveled the country from east coast to west, and can say with confidence there’s no place like it.

My fiancé and I recently sold most of our belongings and renovated an old travel trailer in preparation for a yearlong tour of the lower 48. We didn’t have any plans to return to Nebraska—not anytime soon, at least—and so before we left, we returned to the forest, specifically the Bessey Ranger District. I felt I owed it something. We left from our apartment in Lincoln, drove three hours west to Broken Bow, then cut north on Highway 2, shadowing the railroad until we passed the town of Halsey—the motel, the empty two-pump gas station, the tiny red-roof hunting cabin—and pulled into the forest. We arrived on a Friday evening in late October, the grounds quiet, the entrance unmanned. The Middle Loup River moseyed slowly eastward, the sunset rippling in its flow, the first stars coming to life. Long, perfect rows of bare-root trees and shrubs unfurled on both sides of the river: sand cherry, chokeberry, multiples species of oak and pine and spruce. Several large greenhouses flanked the service road beyond the fence, white tarps stretched tight across the ribs, container seedlings raised several feet off the ground.

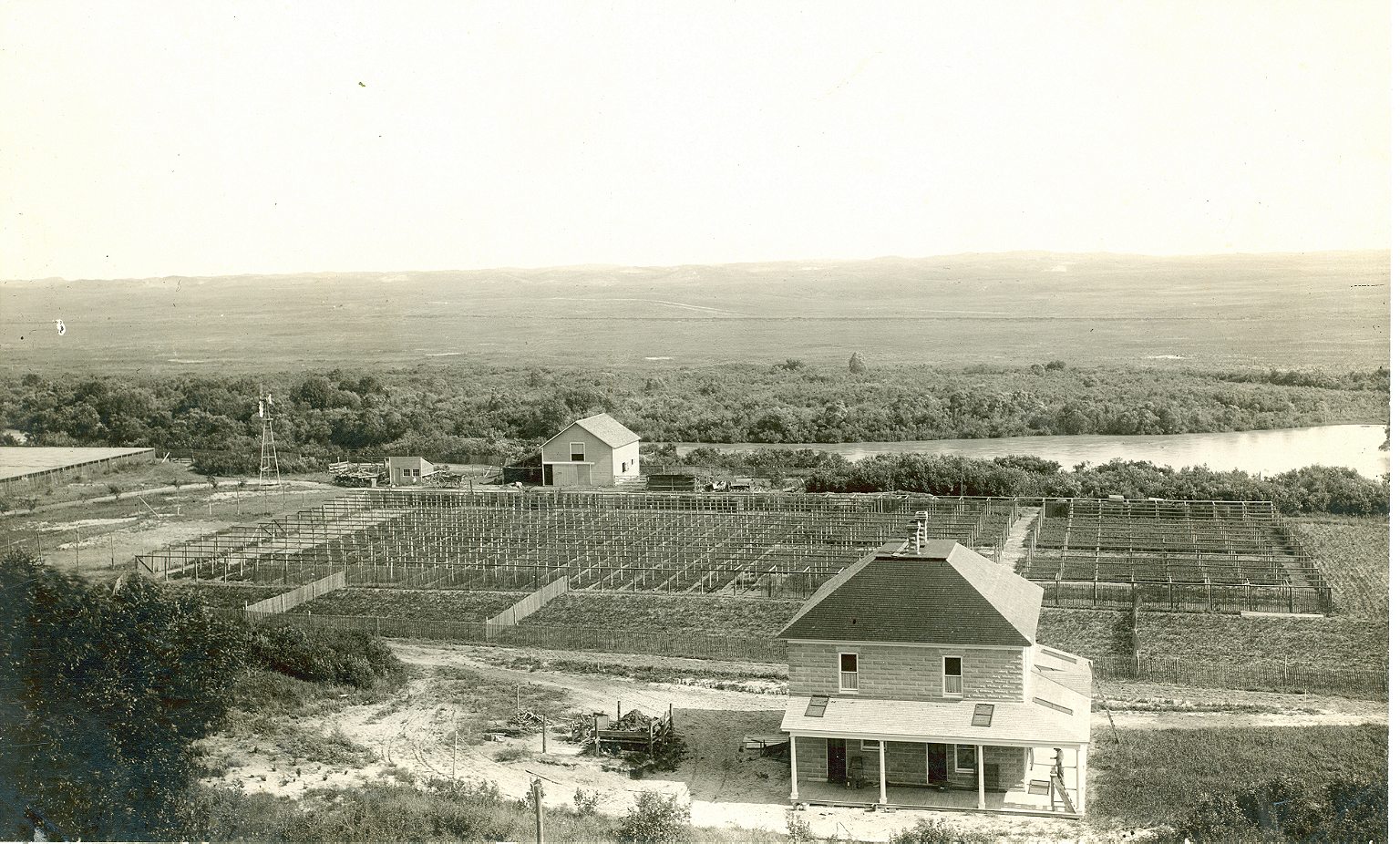

The Bureau of Forestry established the nursery in the summer of 1902—just months after Roosevelt’s proclamation—to grow trees for its great Sandhills reforestation experiment. The nursery gathered yellow pine seed from Pine Ridge and the Black Hills, and blue spruce from northern New Mexico, too. They sowed the first beds in November, completed the nursery headquarters in December, and in the spring of 1903, planted the first 100 acres of what eventually became a 20,000-acre forest. Today, under the management of Richard Gilbert, the nursery provides roughly three million seedlings for reforestation efforts in the Rocky Mountain Region every year. Only a decade later, Bessey had already declared the entire operation “a magnificent success.”

We parked our trailer in the campground abutting the forest, spent the weekend exploring the Sandhills. We took the backroads. We stared at miles of prairie grass, the river slow and brown and slithering through broken sandy banks. We hiked in the ranger district, through hand-planted pines and the kill zones of fires past, stumps littering the hills like soldiers on a battlefield. I thought about Bessey, how real his vision has now become, so fixed in the world of central Nebraska its own residents now take it for granted.

Bessey died of heart failure on the evening of February 25, 1915. His passing made the front page of the Omaha World Herald. Scientists, former students, forestry officials: they wrote in from across the country, all of them praising Bessey in near spiritual tones.

“To have been intimately associated with him and to have walked with him into the fields and gardens and to have received from him an insight into the great realm of which he was master,” wrote his university colleague Raymond J. Pool, “was to have been led very close to the Great Omnipotent who causes the snow flakes to fall.”

We climbed the Scott Lookout Tower, 50 feet tall, built in the 1940s to scan for smoke on the horizon. From the top, we could see forever. Spread out before us was a carpet of pine, the boundaries of the forest clean against the void beyond it, all grass and sky. Bessey complained that writers—“always on the lookout for a field to exploit their imaginations, asking only for a minimum of fact upon which to base their fiction”—often slandered this region, focusing only on the extremes, the heat, the cold, the absence of “mental food.” That Bessey, who arguably more than anyone remade the region based on his own imaginings, should be the one to argue this is ironic. But perhaps he could no more help himself than the writers he criticized; this place does, after all, lend itself to stories.