The Wolgadeutsche, German-speaking people from Russia’s Volga River region, live on in pockets of the U.S. where you can still get a decent meat hand pie any day of the week.

The first time I remember my mother making bierock, she pulled store-bought dough from the freezer, and after a long, unceremonious thaw on the counter, rolled it out into a wide rectangle. She spooned on a savory-sweet blend of hamburger cooked with shredded cabbage and minced onion, folded the dough over like a strudel, and pinched the ends closed. Tucking the seams underneath, she eased the soft doughbaby into the oven. Soon, our apartment filled with the heady aroma of baking bread intertwined with browned beef, underpinned by a cruciferous funk.

When it came out of the oven, the outer crust was toasty and golden and the interior was soft like a steamed dumpling. There wasn’t really anything special about it; it was just the type of meat/starch/veg that she always tried to cobble together, but it somehow superseded any other iterations of the quintessential balanced meal. It was uncanny; it was as though my enjoyment of that one dinner was etched into my very genetic code.

And perhaps it was. I’m descended from the Germans who followed Catherine the Great to Russia’s Volga River Valley in the 1760s to settle the rugged steppe and civilize it with wheat. These Volga Germans—the Wolgadeutsche, or Povolzhskie nyemtsy to the Russians—formed tightly knit, somewhat xenophobic enclaves. Even a century and a half later, they still primarily spoke a Low German dialect, the vernacular of which had remained relatively unchanged for hundreds of years. When they arrived in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, the Wolgadeutsche sounded like they were speaking the equivalent of Shakespearean English to other German immigrants.

It was easier for the small community that ended up in Portland, Oregon to learn English and assimilate than to hope of remaining German, but they held on to their identity in other ways. These German families largely stayed with others from the same Russian villages; my family from Norka (close to modern-day Saratov) settled in a neighborhood in North Portland with other Volga German immigrants, resulting in the Albina area being dubbed “Little Russia.” Families lived in such close proximity to their old neighbors that some people remarked that it was as almost as if Norka had picked itself up and moved halfway around the world.

In America’s Bread Basket and the rolling Palouse of southeastern Washington State and northern Idaho, where Wolgadeutsche landed by the thousands (the familiar expanse of flaxen cereal awns stroking an endless sky must’ve been a comforting sight), many communities went farther, maintaining their language, their old ways, and their identity.

This pattern was repeated everywhere Volga Germans resettled. These people had been accustomed to living as outsiders; they had done so for more than a century in Russia, having defended their German ethnicity during the entirety of their settlement in the Volga River Valley. Although this cultural autonomy helped preserve many of their traditions in Russia, it ultimately culminated in their destruction and exile to Siberia or Kazakhstan during the ethnic cleansing brought about by the Russian Revolution.

And then World War I soured America on Germany while many Wolgadeutsche were still fresh off the boat; my own family had only been in town just two years. At a time when most German-named Portland streets were being renamed after American war heroes, Germans from Russia hadn’t had time to earn the trust of their neighbors. My great-grandparents discouraged their children from speaking their mother tongue, but their accents still gave them away. As a boy, fistfights with aggressively patriotic neighbor kids were a daily norm for my grandpa and his brothers.

Deviation from the Holy Trinity of bierock fillings is unheard of

Volga Germans did largely maintain their foodways, however, a last bastion of cultural continuity. They had survived mostly untouched by their Russian neighbors for decades. Most important among them was the bierock, the canonical Volga German dish and emblem of their culinary identity. The bierock etymologically resembles the Russian pierog or the Turkish boerek, but is closer to the meat pie pirozhki. Nomadic people whose foreign contact was mostly with the laboring peasant classes invented these workaday meals. Like all meat pies, bierocks were an excellent lunch food for laborers who needed to eat in the field; they’re pocket-sized, sturdy enough to sustain a few hours in said pocket, and substantial enough to sustain a toiling farmer.

The bierock is closely related to Middle Eastern fatayer and the chiburekki eaten by the Crimean Tatars. It is thought that spice traders from Central Asia brought meat pies from the Middle East to India, resulting in the samosa. The samosa resulted in empanadas via Portuguese explorers returning from Goa, India. Like these other meat-filled breads, bierocks took on the traits of the people who adopted them, resulting in subtle differences that matter deeply to a stubborn people. Bierocks are not fatayer because Germans don’t believe in eating reheated spinach. Bierocks are to be round and baked, not a fried half-circle like chiburekki. Unlike pirozhki, deviation from the Holy Trinity of bierock fillings is unheard of.

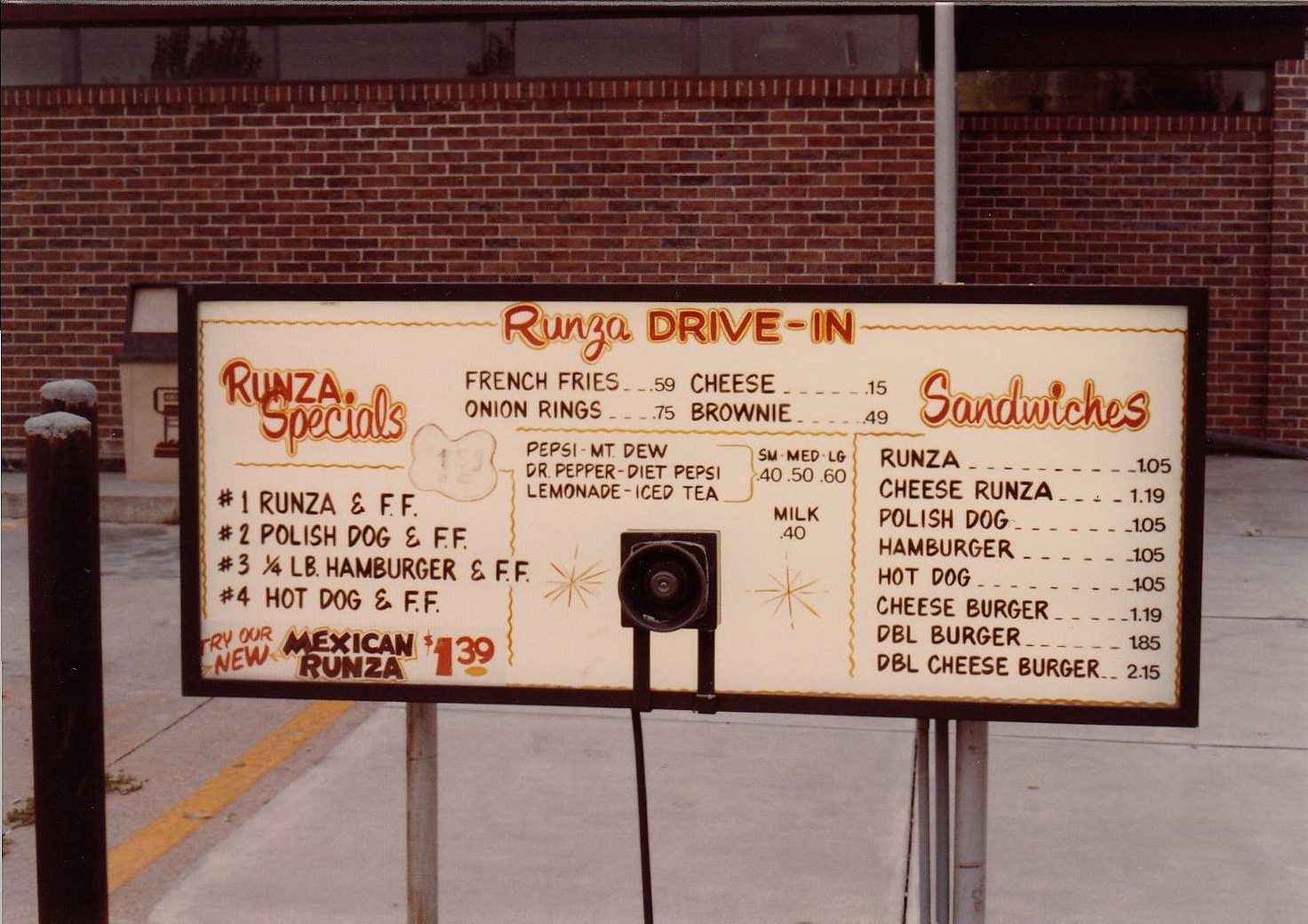

Nowadays, they’re mostly relegated to holidays or the occasional church potluck, but bierocks were once a daily staple. For denizens of the central United States, a reasonable facsimile of the bierock can be enjoyed any day of the week. Alex Brening and his sister Sally Everett (whose family came from the village of Kutter, just three villages away from mine) opened a diner called Runza Drive-In in Lincoln, Nebraska in 1949, about a mile away from one of the original Volga German settlements in Lincoln. With the addition of melted American cheese to the hamburger, their runzas are more like a Germanized loose meat sandwich—a regionally specific culinary aberration from Iowa. The name “Runza” is a nod to the Low German word runsa, referring to a bun or the round shape of a soft belly.

My mom must’ve gotten the recipe she used on that one day from my great-aunt Lydia, who was the last surviving Arndt woman. It’s doubtful that my mom had ever eaten or even heard of “bierocks” before then, nor did she understand that they’re supposed to be made into hemispherical, handheld buns. Last November, after having fumbled my way through the process on my own a few times, I had the chance to learn from some of the elder women in Portland’s Volga German community. Instead of painstakingly rolling out individual rounds to fill and pinch closed, they rolled out one long, flat rectangle of dough and cut the sheet into squares with a knife. Then they spooned the filling onto the squares, pulling up the corners to meet in the middle before pinching them shut.

Using store-bought bread dough should be considered, at best, a last resort. Proper bierock dough recipes are enriched with eggs, butter, and milk, and sweetened with a little sugar or honey, resulting in tender rolls that resemble challah or the German Easter bread osterfladen. My version of the filling is far more highfalutin, daring to branch out from simple salt and pepper to include toasted caraway seeds and chopped fresh dill. Instead of steaming it, I brown the ground beef, cabbage, and onions in a spoonful of the bacon fat and deglaze the browned bits with a splash of brine from my homemade sour dill pickles. After pinching each bierock closed, I like to brush the top of the dough with butter.

The end result is not quite traditional, but it’s close enough; it tempers my desire for tradition with my desire for umami. Although I never had the good fortune to learn this food from my Wolgadeutsche foremothers, I feel their blood coursing through my veins every time I make them. I don’t think they would bristle at my slight tinkering with the recipe. I inherited my resourcefulness from them, after all, and at least I’m not making chiburekki.