How Manoj Chopra went from male beauty contests and fistfights to flipping cars and inspiring millions of Indians.

LUCKNOW, India—

At a Christian fellowship in the capital of India’s northern state of Uttar Pradesh, a strongman sits among a crowd of believers. He wears shiny black track pants, a red sleeveless jersey, and a black short-sleeved button-down shirt designed to conceal his thick upper arms before he takes the stage.

The performance of his feats of strength is one of the highlights of the annual post-Easter gathering of Christians at Lucknow’s Christ Church College. The Uttar Pradesh Masihi Association (a masihi is a follower of Jesus) calls the outdoor event an Easter Milan. A milan, in Hindi, is a meeting or gathering, but on a deeper level, it’s also known as a union of souls. A few thousand people have turned out for the event. The strongman is 45 years old, 6-foot-6, and 375 pounds, with a droopy mustache perched over a rounded cleft chin. Among a sea of supporters, he appears to be a giant.

After some prayers and songs, the night’s emcee, Bishop Anthony, delivers a speech thanking the state government for its support of the Christian community during a controversial, politically fueled religious conversion campaign that swept India last winter. “Ghar Wapsi,” or “homecoming,” was an attempt by Hindu leaders to “reconvert” religious minorities in India back to Hinduism. It remains a contentious issue, though it has largely left the public spotlight.

It’s then time to bear witness to Manoj Chopra’s power.

A theme song befitting that of a wrestling superstar blares out from the speakers. Bishop Anthony begins to pump up the crowd for India’s Strongest Man.

Chopra takes off his black cover-up and walks briskly across the grass and up the short flight of stairs onto the stage. “I’m so happy to be here,” he speaks into the microphone in English, breathless, before switching back to Hindi and introducing himself.

As a young man hands him a thick directory as fat as the Yellow Pages, Chopra explains how he won the titles of India’s Strongest Man nine years ago and Asia’s Strongest Man six years ago. In 2004, at the Strongman World Cup in Canada, he placed 14th in the world. Today, he’s also a motivational speaker at churches, schools, prisons, companies, and anywhere else he’s asked to perform.

Chopra holds up the directory and walks over to the evening’s guest of honor, Abhishek Mishra, a minister in the state government, who is seated at a long table in the rear of the stage. He smiles, rises, and at Chopra’s insistence, checks the book’s thickness. He attempts, unsuccessfully, to tear the book’s pages en masse. He shakes his head when he can’t do it.

A new, upbeat melody that sounds like the soundtrack to a magic show starts to play. Chopra walks to the front of the stage, peers out at the crowd, and begins to rip the book apart inch by inch. He goes down on one knee, then stands again, as he balances the directory on his broad chest. His breath becomes short and shallow. Beads of sweat trickle down his temples as his eyes bulge.

The crowd roars when he raises his arms on each side, showing off the crumpled pages of the directory squashed in his fingers. He had accomplished the feat in less than 30 seconds.

Six cars he owned for his travel agency were involved in accidents on the same day

Chopra’s quest to become a strongman began when he encountered a major hurdle in his life.

In 1996, at his home in Bengaluru (formerly Bangalore), six cars he owned for his travel agency were involved in accidents on the same day. Chopra was distraught. He had moved to Bengaluru in 1991 from his hometown of Raipur, the capital of Chhattisgarh, a steel-producing state in central India, because he had wanted to go into the tourism industry. With no cars, he had no means of earning an income, and no money to cover the massive cost of paying to repair the cars.

Chopra couldn’t handle the stress, and he sometimes flew into violent rages. He often found himself in fistfights, and once beat up his opponent so badly he landed in jail. “My name was in the newspapers, and no one liked me after that,” he says. He felt dejected and lonely. His mother told him he had tarnished his good name, and his family and friends shunned him.

One night, Chopra turned on the television, flipped through the channels, and landed on the World’s Strongest Man competition. Strongman contests have their participants perform daredevil stunts that seem beyond the parameters of human strength: flipping cars, lifting giant stones, stopping vehicles from moving, using teeth to pull a car. Racing against time is often part of the battle. Other variations of the contest focus on Olympic-style weightlifting.

Chopra always knew he was strong, though perhaps not quite on that level. But something about watching the program hit him. “When I saw the World’s Strongest Man Competition, my mind was changed,” he says. “I saw people from around the world, all of them there. But from my country, nobody was there. And I decided I was going to work very hard and take our country’s flag for the world’s strongest man.”

Pradeep Baba Madhok is the former president of the Indian Bodybuilders Federation and the current president of the World Strongmen Federation, one of several strongmen organizations in the world. He says it’s difficult to keep track of all the different bodybuilding and strongmen contests taking place in India because—unlike other countries, which might just recognize one federation—there are a host of different organizations here with different sponsors.

But only competitions recognized by the International Federation of Bodybuilding and Fitness , he says, are legit. The IFBB was established in 1946 and has helped codify bodybuilding and other strength and physique competitions into what they are today. The different bodybuilding and strongmen organizations, and even Vince McMahon’s WWE and other professional wrestling matches, are all spinoffs of the IFBB, according to Madhok.

Putting the industry’s beginnings aside, however, “the strongman culture in the world is the most ancient sport of all,” Madhok tells me during a phone conversation from his home in the northern city of Varanasi.

“The physique culture has been in this country for centuries,” he says. Just as the Roman Empire had its chariot races and gladiator fights, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, India’s ancient Sanskrit epics, also detail stories of warriors and battles. “Even Lord Rama had to pick up a bow and arrow to marry his wife Sita,” Madhok says, referring to the story of the Hindu god in the Ramayana.

Bodybuilding’s history goes back to 11th-century India

Madhok believes a “physique culture” prevails in India in part because of its Hindu mythology. Physique culture is neither about showing strength, the main purpose of achieving strongman feats, nor is it only about the body, like in bodybuilding, where the athlete displays his or her muscles in seven different poses and is judged upon that presentation. Instead, according to Madhok, the “physique culture comprises strength, beauty, and power.”

Rajesh Kumar, a child protection officer researching the Indian government’s policy to promote bodybuilding as a sport, says bodybuilding’s history goes back to 11th-century India. “Men in India have been lifting stone weights, called nals, to build up their health and increase their stamina. There was no physical display of the body,” he writes in a 2014 article in the Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing. Weight training is said to have become a national pastime in India by the 16th century.

A type of Indian wrestling known as pehlwani has a centuries-long tradition as well. It was developed from a combination of 12th- and 13th-century Hindu practices with Persian wrestling the Mughals brought with them to the subcontinent in the 16th century. Babur, the first Mughal emperor, is said to have been a wrestler and ordered wrestling contests as entertainment. More recently, Gama the Great, the stage name of the Punjabi wrestler Ghulam Muhammad, was a world champion from 1910 until about 1950.

Anthropologist Joseph Alter writes that Gama became an allegory for Indian autonomy and masculinity in the country’s path toward independence. The fight for freedom played out in his body as he traveled the world stage. The mythology helped contradict colonial stereotypes that Indians were listless and helped establish that there was in fact an Indian physical culture.

Madhok, meanwhile, attributes Indians’ attraction to modern-day physique culture to a particular man—Manohar Aich, a 4-foot-11 Bengali centenarian, who, in 1952, became India’s first Mr. Universe, the grandest title for a bodybuilder. The “Pocket Hercules,” as he was known, inspired millions of Indians.

Chopra’s conversion to bodybuilding wasn’t the first time he had flaunted his body in competition. In 1986, at the age of 16, Manoj Chopra participated and won a male beauty pageant in his home city of Raipur. It was the first and last time the city had a beauty contest of that kind, he says. It consisted of three different rounds. For two of them, he had to show himself in his best dress—blacks slacks, a white dress shirt, bow tie, and a jacket he either wore or held over his arms. The other round was a Q&A, where he had to answer questions like, “What does India mean to you?” and “How important are your friends and family?”

Chopra won the title of Mr. Madhya Pradesh (Chhattisgarh, the state from which Chopra hails, was carved out of Madhya Pradesh) and became devoted to the gym and training.

“When you become a Mr. M.P.,” he says, “after that you want to go for Mr. India. So you should have a good physique, be slim, and look good.”

He began his bodybuilding career with a weightlifting competition in Raipur. With a coach’s training, he worked out daily, training for both the weightlifting portion of the competition—which involved the “clean and jerk” movement of lifting a weighted bar from the ground and over one’s head—and powerlifting, which featured bench presses, dead lifts, and squats.

He took first prize at the competition, and was hooked on the sport. He put aside the beauty aspect of gym culture and focused more on strength training. The next year, he became the state weightlifting and powerlifting champion. In 1989, he won a state arm wrestling contest.

When Chopra saw the World’s Strongest Man competition on television that night in 1996 and thought to compete himself, it wasn’t a completely wild idea. He began training and participating in different open challenges in Bengaluru and elsewhere when he could. Eventually, he won India’s Strongest Man in 2000.

He lived in Los Angeles for a year and a half to train for the WWE. During that time, he worked in a gas station and cleaned cars and toilets to support himself. Money was tight and he would eat meals in the middle of the day at cheap buffets. “I would think, if I eat food early, I would feel so hungry by the night!” he says with laughter. Financial struggles eventually forced Chopra to give up his WWE dreams.

Back at the Easter Milan in Lucknow, Chopra did not stop any cars with his bare hands or break giant stones into pieces, both feats he once performed with regularity.

Instead, Chopra entertains the crowd with stunts that fill them with awe and laughter. He shatters the bottoms of beer bottles by slamming his elbow on the bottles’ tops, bends a frying pan in half, and blows up a rubber hot water bottle bag to such full capacity that the balloon pops. Later, he balances two small boys on a metal rod that he lifts over his head and swings in circles. The crowd gasps.

The World Strongmen Federation recently launched the Strongman Federation of India. It is also developing a reality show to find contestants to compete in the 2016 World Strongman Federation World Cup and will have a Strongest Man of India competition in Goa in October.

But these days Chopra is less concerned with competing in strongman competitions himself. In Bengaluru, where we meet at his friend’s gym a few months after the Lucknow event, he explains that he’s now focusing on helping his son train to compete in strongman competitions. He’s also more interested in using his strength to spread morals and values, which is why he incorporates it at motivational speeches at churches, schools, and prisons. It’s part of his belief system. “I’m from a Hindu family,” he says. “But I believe in Jesus.”

It’s not quite a conversion, he says, which he knows might rile some Indians. It’s a personal relationship he found in the 1990s when he asked other bodybuilders and strongmen he met how they found their strength. It’s also helped him control his temper and rebuild relationships with family and friends.

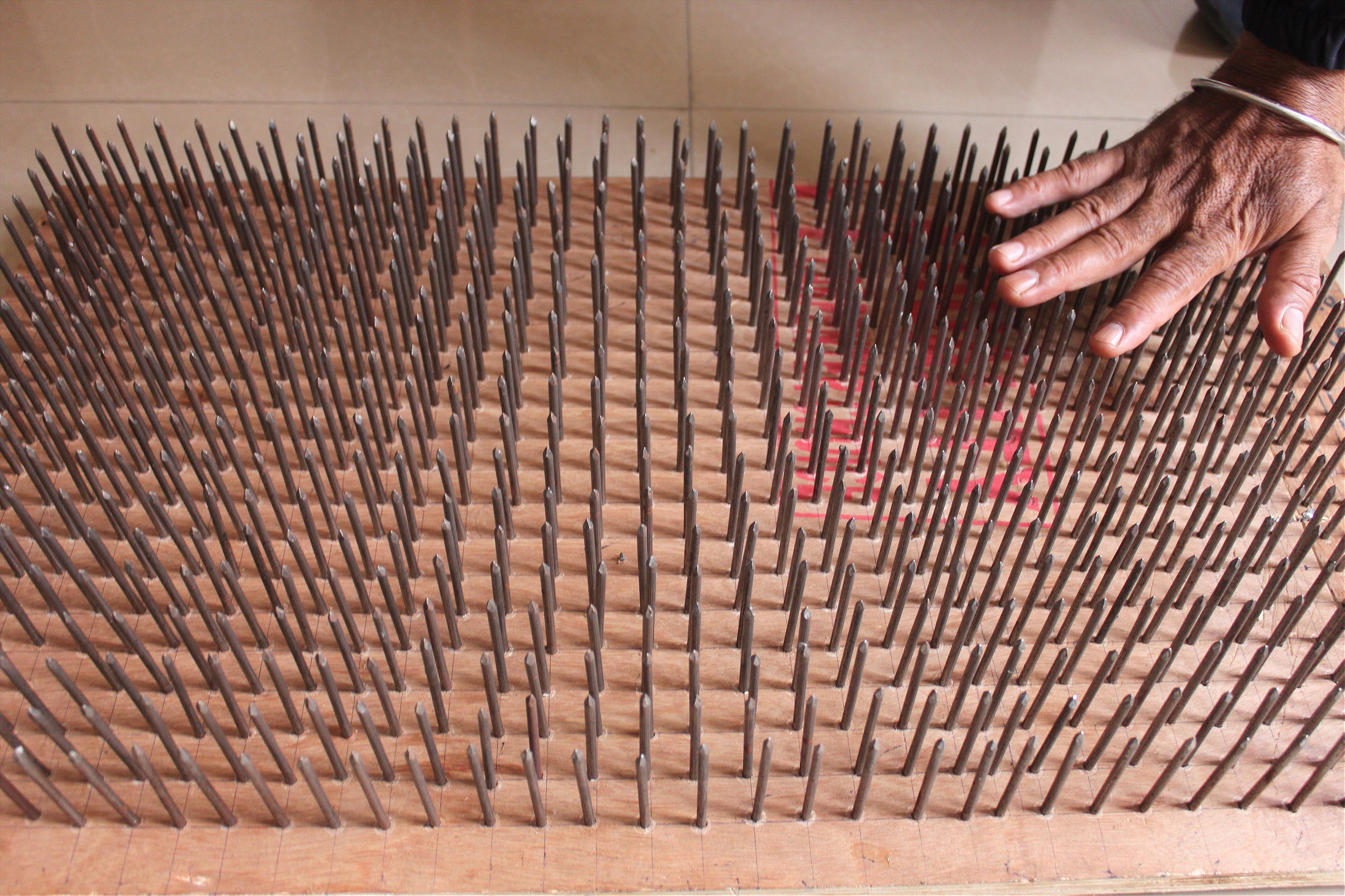

Steve Deva, Chopra’s friend and a former bodybuilder who runs the gym Chopra goes to, says people can relate to values much more vigorously when they see it performed in a kind of stunt, like lying on a bed of nails to demonstrate bearing pain (which Chopra can also do) or breaking beer bottles to discourage heavy drinking. “They enjoy the ‘Pow!’ ” he says, smiling and pumping his fist. Maintaining proper health and fitness, which they also preach, goes back to the age-old idea that physical strength reinforces mental strength, and vice versa.

“I would be happy to see our country’s flag up high,” Chopra says, recalling how India’s flag wasn’t represented on the strongmen competition he watched that night in 1996. “But more than that, I want to do something for the society and for my country. I want to do a good thing also.”