Revolutionary writer Alejandro Murguía emerged from San Francisco’s famously eclectic—and rapidly gentrifying—neighborhood to become the city’s first Latino poet laureate.

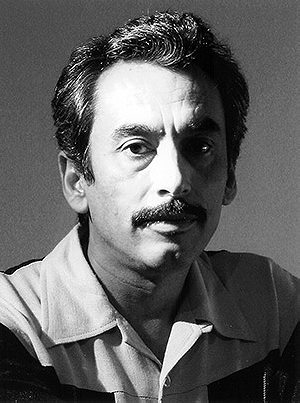

A lean, mustachioed Latino man sighs behind a microphone, stares out into his audience, and begins to read aloud, in the long, drawn out vowels of a street poet, a piece called “The World Upside Down”:

It’s a stra-a-a-nge world we’re living here

Where fat buzzards perch on trees –

His voice is smoky. The poems seethe and pop like jazz, their imagery swinging from Magnum-wielding cops to barefooted children. The audience at City Lights Bookstore at Columbus and Broadway in San Francisco’s North Beach, mostly white men and women of upper middle age, nod appreciatively, chuckling along when the poet disses the Man.

It is an odd pairing of lyrical artistry and barely veiled rage, and it is signature Alejandro Murguía. This is the man dubbed “the voice of La Misión.” The title refers to San Francisco’s Mission neighborhood, a diverse and constantly evolving district known by turns for its working-class immigrants, political protests, and most recently, rapid gentrification. Murguía emerged from the Mission in 2012 from decades of writing, social activism, and cultural leadership, to become the city’s first Latino Poet Laureate.

Not all of his poetry is angry; it can be sensual or dreamy, funny or wistful. And not all of his work is poetry. Murguía has been an established contributor to the San Francisco literary scene for 30 years, with a book of stories, several memoirs, and multiple anthologies published since 2002.

Now, however, his star is firmly on the rise, and his locally centered work is striking a chord both inside and outside the Mission, bringing his causes to a wider audience. His is “a poetry,” as one critic puts it, “that arms the resistance.”

Murguía was born in California and has lived in Mexico City and Tijuana. As a young man, he moved to San Francisco to be a part of the Chicano movement for Latino equality. In the little pocket of San Francisco bounded by Highway 101, Guererro, and Portrero Street, Murguía found friends, inspiration, and home.

“It’s like John Steinbeck writing about Cannery Row,” Murguía tells me. “His sense of telling stories about the everyday people of California; that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m not ‘documenting’ the Mission. I just write about it because it’s home.”

Perhaps like any home, the Mission of Murguía’s writings provides complex context. There are beloved people, and old, deep wounds, and the smell of home cooking—cilantro, cumin— drifting out the windows. He makes it clear that there is both beauty and blood on these streets.

The beauty is not hard to find here. On a late spring day the sun is shining, as it nearly always does in the Mission’s idyllic microclimate. Around every other corner, the murals for which the district is famous enliven walls with brilliant colors; here a lively scene of Prohibition-era shenanigans, there a graffiti tribute to the Virgin Mary.

People smile at strangers, seeming happy to be out and about. Thirty-somethings clack away on rows of laptops on a café’s refurbished wooden tables, right next to abuelitas perusing the rows of a mercado’s oranges, plantains, peppers, and limes. Like Murguía’s poems, street vendors switch effortlessly between English and Spanish, though the Spanish comes in many varieties— Nicaraguan, Mexican, Cuban, Guatemalan, Salvadoran. The scene feels friendly, modern, and urban with an interesting international flare.

But the Mission is a neighborhood in transition. Once almost entirely Latino, the Mission’s composition began to evolve in the 1990s. With the dotcom boom, money began to come into the neighborhood in uneven waves. Inequity grew. Housing prices soared, forcing many renters out. Some left for other neighborhoods; others ended up on the streets.

The abrupt changes have left the Mission vulnerable to drugs, crime, and an unfortunate new scourge: fires. These have become an epidemic. Rising property values motivate some landlords to torch their own buildings for the insurance money, although arson has only been occasionally confirmed. On a recent afternoon, 24th St. and Capp is just one of many Mission street-corners where the air smells like campfire. A bright red and blue luchador costume peeks out from an otherwise blackened pile of someone’s burnt belongings.

Murguía’s short story, The Other Barrio, recently made into a movie and shown at the San Francisco Independent Film Festival, centers on a suspicious fire in a Mission residential hotel. He calls it “a magical realism piece,” based on the true case of insurance arson at the Gartland Street apartments at 16th and Valencia.

The film’s credits read like a Who’s Who of today’s Mission activism, and Murguía is clearly proud of the project. “It’s a collaboration of artists, engineers, actors, writers, all these people, in response to this big issue,” Murguía says. “Sometimes when politicians can’t, or won’t, solve a problem, it becomes the responsibility of the artists.”

The film has already resonated with locals. The Mission’s bilingual newspaper, El Tecolote, is unambiguous in its approval in a January review: “The film exposes the economic and racial inequalities Missionites see day to day… The story is labeled as fiction, but if you live in the neighborhood, it might feel like a documentary.”

Posters in a Valencia Street bakery window betray an even more chilling issue troubling the community. Bold pink font calls for an April 14 community protest. “Stop Business as Usual! Stop the Murder of Black and Brown by Killer Cops!”

As the nation has grown tense over issues of police violence, the Mission has been a microcosm of the issues raised in Ferguson, Oakland, and elsewhere. The neighborhood was already reeling from the San Francisco Police Department shooting of 28-year-old Alejandro Nieto last March; in February a young Guatemalan named Amilcar Perez-Lopez was shot and killed by police.

For many Latino Missionites, any sense of trust in law enforcement has been shattered. At SFPD initiated community meetings discuss the issue, Perez-Lopez’s neighbors refused to be placated, shouting in Spanish, “Lies!” Members of the community repeatedly accused Mission police of unnecessary deadly force, and asked why more Spanish-speaking officers were not assigned to the district.

Asked about the shootings, Murguía inhales and pauses, then chooses his words carefully.

“It’s a complex issue,” he says. “I’m going to reserve judgment on that, for now. I don’t want to incite people.”

This, of course, is the same man who last year published a poem aiming one of the most vehement Spanish curses at “every hijo de la gran puta who ever asked for my green card, my ID card… my registration, my driver’s license.”

Murguía writes love poems, too, but none for the police.

On the one-year anniversary of Nieto’s death, one of Murguía’s early projects became a venue for many of his friends, family, and other Mission locals to express their anger, grief, and confusion. Murguía and others founded The Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts in 1977, as a place for Mission artists to collaborate.

On March 21, the MCCLA and its surrounding streets are filled with hundreds of people wearing t-shirts that read, “Amor for Alex.” They gather for a Lowrider rally, a series of chants, prayers, songs, and four films, all of which present Nieto as a friendly, loving young activist killed without reason or justice.

In the MCCLA theatre, as the pounding drumbeat of a danzantes dance troop fades away, the audience holds a collective silence as the audio of the police gunshots that killed Nieto plays overhead. Soon after, Murguía stands to recite his poem, “El Mundo Al Reves”:

It’s a strange world we’re living here…

This time there is no irony in his voice. No one chuckles. Many audience members quietly weep.

“I have three kids, and two of them are young men,” says Mission resident Beatriz Mero afterwards. Her family has owned a home in the neighborhood for generations. “My sons, they are 24 and 20. They’re good boys, like he was.” She gestures to the screen where home videos of Nieto have just played. “But I worry for the one day, the one interaction with police, the one misunderstanding. It’s terrifying to be a mother of a young man of color in the Mission.”

On ordinary days, nestled between two bilingual bookstores and across the street from a fragrant, bustling tacqueria, the MCCLA sits under a mural of muted colors that belie the center’s radical roots.

Here huge peace marches gathered in the 1970s that would parade down to 18th Street. Here artists, writers, and thinkers gathered to create art in solidarity with the Sandinista movement of Nicaragua, before many of them left to fight the 1979 revolution. Murguía was among them. It was a time of exhilarating unity for the Latinos—Chicanos—of the Mission, and the MCCLA was at the heart of it.

Today the center offers workspace to artists, a theatre for small, Latino-centric films, and classes for the community. The polite, curly haired woman at the desk enthusiastically lists the dance classes, not just tango and samba, but belly dancing, Bollywood, and b-boy. She has no idea who Alejandro Murguía is. On days when there are no protests swirling around the center, it seems like the furious energy that once tornadoed into the Chicano movement is now channeled into Basic Latin Percussion every Thursday at 7 p.m.

At 24th Street’s legendary Café La Boheme, too, there is a sense that the glory days are over. Once such a gathering place for exiled revolution leaders that it was dubbed “the Central American Embassy,” Café La Boheme now vies with uber-slick hubs like Philz and Haus for the skinny-jeans demographic.

The Mission is going to the hipsters, and has been for over a decade. “It’s not even a story anymore,” says John Zucca, a gray-haired biker with tattoo-sleeved arms as colorful as the murals themselves. He is repairing his motorcycle outside his home, one of several properties he owns on or near historic Cypress Alley, where the murals of the Mission all began.

“Everybody talks about gentrification like it just started happening. But I remember when tech started showing up—must’ve been ’90, ‘92? That building used to be all Latin families.” He waves a hand at a bland blue apartment complex, rare in this part of the Mission, across the street. “I don’t blame them for taking the buy-out, and I don’t blame the developer for selling it at top dollar to the dot-com kids. Neighborhoods always evolve.”

Zucca shrugs. His is an attitude that resurfaces over and over in non-Latino commentary on the issue: change happens, this is just the next stage of it.

This mindset frustrates Murguía. “Change? Change is natural. But change is different from the aggressive and purposeful description of a culture.”

Murguía has a theory on who is behind the destruction. “It’s not just one entity. There is a complex amalgamation of power and wealthy corporations.” He mentions Google. “Young technocrats with a lot of intelligence and not much human compassion. And unfortunately, politicians are bought and sold. So you get the lawkeepers protecting the lawbreakers.”

According to Murguía, this is nothing new for the Mission district. In his poet laureate inaugural address, Murguía said the Mission’s history is inextricably linked to displacement. From the indigenous Raymaytush tribe dislodged from land here, to the Mexican residents of a barrio disrupted by the Bay Bridge and emptied into the Mission, to the exiled revolutionaries who found refuge on 24th Street, Murguía sees struggle at the heart—el Corazón—of the Mission.

Yet there is a tiny, irrepressible note of hope, both in Murguía’s poetry and in his conversations about the Mission. When he predicts what the Mission might be like twenty years from now, the lines that have furrowed Murguía’s brow in a lifetime of protest relax. He gets excited.

“I think 24th Street will be a protected, cultural corridor. The sidewalks are too narrow now, yes? But it will become a pedestrian walkway.” Murguía pauses, as if laying it all out in his mind. “It will be this vibrant artery of bookstores, print shops, publishing houses.”

His voice soft, Murguía returns to the theme of home. “It’s the people that make it home.” He tells about his own people: the owner at Café La Boheme; a fellow revolutionary from the old days; a 24th Street fishmonger who has become a dear friend.

Then Murguía mentions another of the Mission’s cultural makers, René Yañez, who helped kick off the mural project for which the district is now known.

“And René? He starts these movements, and now he’s being evicted from his home? How can this be?”

And the anger is back.

In his poem “16th and Valencia,” Murguía peoples his Mission with outcasts who are somehow beautiful, crazy, and subversive all at once, then aligns himself with their outrage:

I joined… the waitresses the norteño trios the flower sellers

the blind guitarist wailing boleros at a purple sky

the shirtless vagrant vagabond ranting at a parking meter

the spray-paint visionary setting fire to the word

and I knew this was the last call…

and we were going to stay angry

and we were not ever leaving

not ever leaving.

Perhaps the struggle now is simply that—to stay, in a Mission that is, like Murguía’s poetry, sometimes dancing, sometimes bleeding, and always defiantly bright.

[Header image: “Mission District Mary: San Francisco, California” by Beau Rogers]