The Mouth‑Numbing Chill‑Out Elixir That’s Better Than Booze

The Mouth‑Numbing Chill‑Out Elixir That’s Better Than Booze

Kava in Togalevu

I had been dry for two months by the time I first tried kava. I was traveling in the South Pacific for work, and due to a number of understandable reasons, there was a strict no-drinking rule that blanketed the trip.

It was going great. My thoughts were lucid, my body sprightly, and I found myself leaping from bed each day with some previously unsourced energy. I can’t deny that I missed it, though; the camaraderie of clinking glasses and the ceremony that surrounds a few rounds spinning yarns with friends. But rules were rules, so I forged on without a brew in sight, unknowing that the camaraderie and ceremony that I was missing would come in the form of a ground-up root strained into muddy water, commonly known as kava.

I had arranged to stay in Togalevu, a small village on the eastern side of Viti Levu, the largest of the Fijian Islands, where I would be doing some volunteer work. I knew that kava was a huge part of the culture here, and as my bus curved around the coastline towards the village, I wondered when I would get my first opportunity to try it.

As it happened, it didn’t take long. Upon arrival, I sat facing the entire village in the community hall, where the kava was being mixed in a big wooden bowl that stood on four short legs. One of the villagers, a young Fijian fellow with an enormous gap between his front teeth, strained the ground kava root through a T-shirt, turning the water a muddy brown. He kneaded the T-shirt with both hands, massaging out as much of the kava as he could. The villagers all watched, transfixed. After he had strained sufficiently, the young man stirred the water slowly, repeatedly scooping and pouring it from a halved coconut shell.

It was a lengthy ceremony. I was welcomed in rapid Fijian by enormous stern men. I then expressed my gratitude to the village for hosting me. And then we drank kava. I went first. The gap-toothed fellow poured a decent bowl of kava and it was passed to me. I clapped once, (a custom that was explained to me before the ceremony) drank it down, then clapped three times before pronouncing my thanks with a hearty “Vinaka!” After that, the spell was broken. Kava is a relaxant and its effects are felt instantaneously. As my lips and tongue began to tingle and my throat grew numb, the men, who seconds ago looked unshakably firm, broke into grins and clapped enthusiastically at my effort.

Kava became a staple part of my time in Togalevu. After a day laboring with the men, we would invariably lay down our tools and head to the community hall to mix our first batch. I learnt how to control my kava buzz through tidal increments, indicating I wanted a low tide for a shallow cup, a high tide for a full cup, and a tsunami if I was feeling brave enough to chug an overflowing and particularly deep shell. Into my second week, I became curious. This plant was such a pivotal part of the culture here. Kava ceremonies were performed in the most important of social and religious occasions. During my own welcoming ceremony, a bundle of tangled kava root was presented to the chief on my behalf. He took it, nodding solemnly and held it to his chest like a baby. I wanted to know more about its story and see the process for myself, from plant to kava cup. I asked my friend Abraham (the kava mixer from the opening ceremony) if he could show me. He grinned his gap-toothed grin and said tomorrow we would do just that.

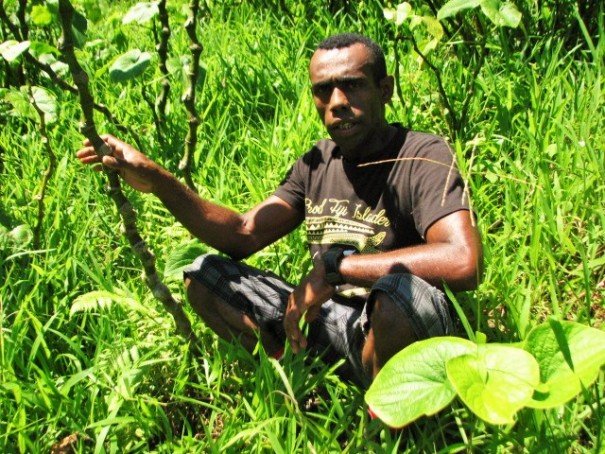

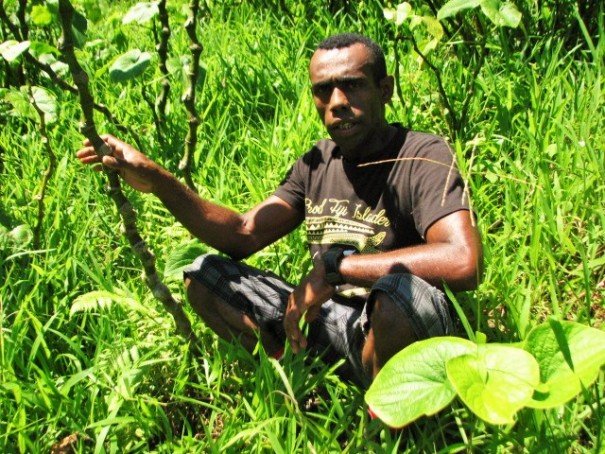

Abraham’s kava plantation was cradled in a valley on the way up to Joske’s Thumb, a rocky mountain peak behind the village that juts out of the greenery and resembles, unsurprisingly, a thumb. We walked barefoot through the tall jungle in the weighty heat of day. After a few river crossings, we broke from the path and waded up a field towards the kava plantation. A member of the pepper family, it was thin-stalked and looked similar to cassava. Abraham handled the leaves affectionately and smiled down at me as I struggled to keep up on the steep climb in the midday heat.

“The reason Fiji kava is so strong,” he said, “more than Vanuatu or Samoa, is the sun. We let it grow longer, let it get stronger.”

We sat under the shade of the kava leaves and he walked me though the process from planting to the drink that I had come to enjoy every night after dinner. The plant must be matured for five years before it is cut, sun-dried, pounded, then strained and mixed with cold water. Abraham told me about kava‘s role in his family. Two of his brothers worked in the kava plant down the road. He laughed as he described how it was used as a sort of informal dispute resolution tool, something that, when shared, erases all animosity or conflict.

“My father was one of five brothers,” he told me. “Oh, they would fight! But then, when they mixed the kava and sat around to drink grog together, whatever they fought about, it was forgotten!” he laughed.

In the community hall, later that evening, I saw how this could be the case. Rather than the rage-fueling properties of, say, whiskey or rum, the numbing, sleep-inducing qualities of the root turned drinking buddies into friends rather than drunken rivals. With heavy eyelids I gazed around. One man lazily strummed at his guitar, another was already sleeping with his palm in his hand. The others told long, drawn-out jokes which were met with soft chuckles. At one point, Abraham leaned towards me.

“This is what we do.” He said softly. “We tell stories and we drink our kava.”

I listened, even though I couldn’t understand, as stories passed around the circle. Eventually, when my eyes could no longer stay open, I said goodnight and stumbled off in a haze to bed, for another dreamless kava sleep.