He was famous beyond Cuba’s shores for his mighty endowment, a symbol of an era of sex and sin. But when the revolution came, he disappeared

“That ain’t no fake. That’s real. That’s why they call him Superman.”

—Fredo, The Godfather Part II

The mayor’s son drew on his cigarette, thought back sixty years, paused, and made a chopping motion on his lower thigh—fifteen inches, give or take, from his groin to just above his knee. “The women said, ‘He has a machete.’”

The mayor’s son is in his seventies now, but he was a teenager back then, during the years of Havana’s original sin. He thought back to his father as a young man, a lotto numbers runner who rose to the mayoralty of the gritty Barrio de Los Sitios, in Centro Habana. His dad loved mingling with the stars that flocked to the capital, and he sometimes took his boy to meet them: Brando, Nat King Cole, and that old borrachón Hemingway. The mayor’s son once got blind drunk with Benny Moré, the famous Cuban crooner who had a regular gig at the Guadalajara.

But more revered than all the rest was the man of many names. El Toro. La Reina. The Man With the Sleepy Eyes. Outside Cuba, from Miami to New York to Hollywood, he was known simply as Superman. The mayor’s son never met the legendary performer, but everybody knew about him. The local boys talked about his gift. They gossiped about the women, the sex. “Like when you’re coming of age, reading your dad’s Playboys. That’s what the kids talked about,” he said. “The idea that this man was around in the neighborhood, it was mind-boggling in a way.”

Superman was the main attraction at the notorious Teatro Shanghai, in Barrio Chino—Chinatown. According to local lore, the Shanghai featured live sex shows. “If you’re a decent guy from Omaha, showing his best girl the sights of Havana, and you make the mistake of entering the Shanghai, you’ll curse Garcia and will want to wring his neck for corrupting the morals of your sweet baby,” Suppressed, a tabloid magazine, wrote in its 1957 review of the club.

After the revolution, the Shanghai shuttered. Many of the performers fled the country. Superman disappeared, like a ghost. No one knew his real name. There were no known photos of him. A man who was once famous well beyond Cuba’s shores—who was later fictionalized in The Godfather Part II and Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana—was largely forgotten, a footnote in a sordid history.

In the difficult years that followed, people didn’t talk about those times, as if they never happened at all. “You didn’t want to make problems with the government,” the mayor’s son said. “People were afraid. People didn’t want to look back. Afterward, it was an entirely new story. It was like everything didn’t exist before. It was like Year Zero.”

And into that void, the story of Superman disappeared.

Havana was unusually cool. It was late January, weeks after President Obama announced normalized relations with Cuba. We stayed in the city’s Vedado neighborhood in a casa particular, a musty rental apartment owned by an aging former diplomat. The chilly sea breeze fluttered the flimsy curtains covering the windows. The apartment overlooked the Riviera hotel, built in 1957 by the mobster Meyer Lansky; beyond that was the Malecón, the seaside highway and the city’s hub of social activity.

I had come with photographer Mike Magers to trace the story of Superman, or whatever we could find of it. It had begun as a curiosity for us but eventually evolved into a strange obsession. We had discovered Superman in a brief mention in a Vanity Fair oral history of the Tropicana Club. Here was a man with a supposedly 18-inch unit who starred in live sex shows, celebrated in Cuba and beyond, and yet virtually nothing was known about him. We were intrigued. Cuba, with profound changes afoot a year after Washington reopened relations with Havana, is having to think about what kind of country it wants to be. It’s a question that naturally calls for a clear-eyed look at the kind of country it once was. What better place to start looking than with the legend of Superman?

Unfortunately, clues about who Superman was and what happened to him were virtually nonexistent. In New York, we met a few Cubans from the diaspora looking for leads, but we had nothing concrete by the time we boarded the plane from Havana, via Cancun, other than a short list of names of people who might know someone who knows something.

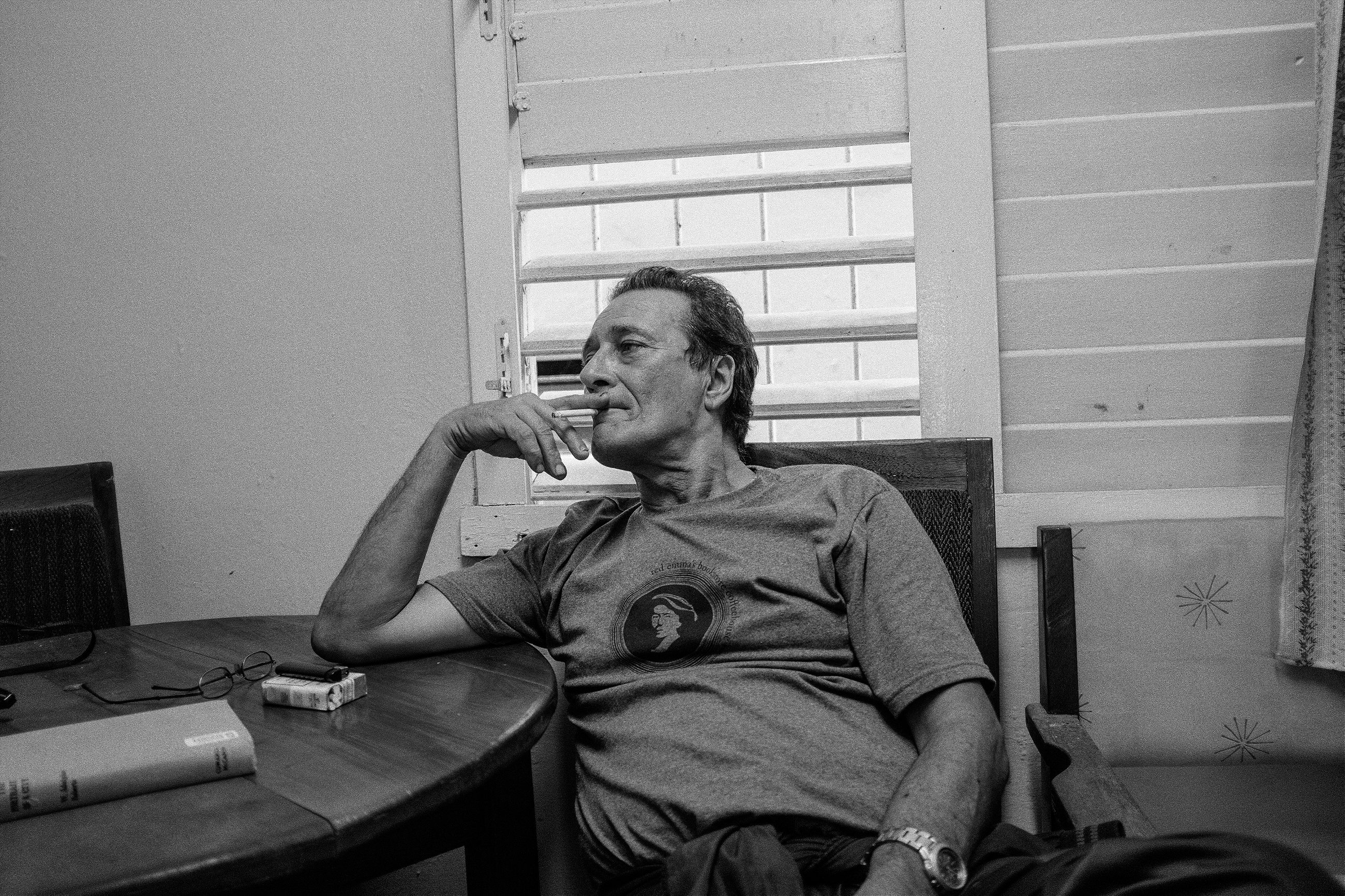

A contact had referred us to a man named Alfredo Prieto, an editor at a publishing house who was working on a book about 1950s Havana, and we paid him a visit on our first day in the city. Prieto was 60 years old, a heavy smoker with black hair and a laid-back demeanor. When we met in his office in Vedado, he seemed bemused by our quest. Superman, it turned out, was a fascination of Prieto’s as well.

“Superman was by far one of the main attractions for Cuba,” he began. Not only did Superman perform at the Shanghai and other clubs, but he also did private sex shows for wealthy Americans. “Superman, as a character, was very deep in the American imagination. They had a saying: ‘Cuba is a place where conscience takes a holiday.’”

Prieto had been investigating Superman for his forthcoming book. He’d found a few people who knew the man, but his story remained a mystery. Most of it was rumor, hearsay, maybe true, maybe not. His name might have been Enrique. He lived in Barrio de Los Sitios, across from a church. Sitios was a working class neighborhood located next to Chinatown, where the Teatro Shanghai was based.

In the Latin American Library archives in New Orleans, Prieto had found testimony from American tourists who described Superman as “the Man with the Sleepy Eyes. Male, forties, handsome, tall, with a penis from here to the corner.” Prieto said he’d heard that Superman had died in Havana, living in hiding and working as a gardener. But no one knew for sure if this—or anything else—was true.

I asked if we could talk to the people he’d interviewed, those who knew Superman. He said he would try to set up a meeting, but that it would be unlikely that these people would talk to foreign reporters. They were still ashamed, still afraid of the consequences of talking about that period. I also asked Prieto how a man who had once been so famous could completely vanish—not just from the island, but from history itself. Why were there no photos of him? How could no one know his true name, or what became of him? Did he even really exist, or was he just an urban legend, a myth?

He told me that after the revolution the regime tried to erase the past. The Fifties in Cuba was an era of graft and corruption, mobsters, and American money. It was an embarrassment, a stain, and Superman was the human embodiment of that stain. The era became dangerous to even talk about in Fidel Castro’s Cuba.

But in 2015, as relations between Cuba and the U.S. began to thaw, that time was finally being reexamined, Prieto said. Cubans wanted American tourist dollars, but they didn’t necessarily want to go back to the excesses of the 1950s. “One of the things they’re saying loud and clear is: one, we have to avoid the mistakes of the past; and two, we have to avoid ‘Cancunization.’ And ‘Cancunization’ is a metaphor for fake.”

Prieto asked us to fill him in on any leads we could find. “It’s a mystery. I try to follow la pista, but at some point it just”—he snapped his fingers—“vanishes in the air.”

Havana, 1959. The eve of the revolution. Fidel Castro waits in the Sierra Maestra while in the city the clubs and cabarets overflow with tourists, gangsters, and movie stars. Ernest Hemingway, at the peak of his fame, lives by the water outside town; Tennessee Williams, a regular visitor from his home in the Florida Keys, is a fixture at El Floridita. Showgirls draw crowds by the hundreds to the dazzling Tropicana Club. The hotels are booked: the Florida, the Nacional, the Riviera. The mobsters, in bed with dictator Fulgencio Batista, are taking over the city; they envision casinos and resorts stretching from Havana to Varadero, 95 miles down the coast.

“Havana is incomparably the chief city of the West Indies,” noted W. Adolphe Roberts in his 1953 book, Havana: The Portrait of a City. “The influence of pleasure seekers from the United States has swelled yearly, reaching a figure that makes Havana the principal tourist resort of the Western World. Nothing apparently can halt its growth.”

Those were ominous words, it turned out. Corruption, crime, decadence, and economic disparity fueled Fidel’s revolution and earned the island an unfortunate reputation as the “whorehouse of the Caribbean.” Americans came in droves looking for release, for glamor, for drink, and, in no small part, for sex. People came to Havana for many reasons, but one loomed larger—quite literally—than the rest.

According to lore, Superman first had sex with female performers, who were bound to a pole and acting with exaggerated terror, and then invited women from the audience to participate. In Vanity Fair’s oral history of the Tropicana, Rosa Lowinger, author of Tropicana Nights, said that she’d heard Superman would “wrap a towel around the base of his cock”—which she tapped at 18 inches—“and see how far it could go in.”

In 1955, the late journalist Robert Stone was a 17-year-old radio operator with an amphibious assault force in the U.S. Navy. His ship, the U.S.S. Chilton, docked in Havana, where he embarked on a bender fit only for a sailor. In a 1992 piece for Harper’s Magazine, Stone describes attending a show at the Shanghai. “The Shanghai was a blue-movie parlor and burlesque house that was home to the Superman Show, the hemisphere’s paramount exhibición.”

The Superman Show, Stone recounts, featured a blond performer “whose deportment was meant to suggest wholesomeness, refinement, and alarm, as though she had just been spirited unawares from a harp recital or a public library.” The other performer was a black man “who astonished the crowd and sent the blond into a trembling swoon by revealing the dimensions of his endowment.” Stone continues, “Suffice it to say that the show at the Teatro Shanghai was a melancholy demonstration that sexism, racism, and speciesism thrived in pre-revolutionary Havana.”

In the piece, Stone confesses to sleeping through much of the show, so his account must have come from others who witnessed it; he never explicitly states whether live sex occurred. Roberto Gacio, a Havana theater historian, doubts that there were actual live sex acts at the Shanghai. Instead, the show was what he called “a sexual revue.” There was sketch comedy, double entendre, word play. Gacio suspects the live sex shows occurred in private shows for wealthy viewers.

James Brody, another journalist, recounts a trip to Havana in the mid-1950s, when a cab driver arranged a meeting with Superman, whom Brody describes as a the “indefatigable star of the best of all the sex shows.” They met in an old and empty theater early in the morning, where Brody was ushered upstairs to meet “an affable, handsome but sleepy-eyed young Cuban, barefoot but in well-tailored tan gabardine slacks and a white t-shirt draped over his shoulder.” The two men spoke in English about Superman’s “sex appeal and staying power,” and they shook hands before parting ways. “That handshake was the limpest I had ever experienced. Clearly, ‘Superman’ was conserving his strength for the evening’s performances.”

Superman later became a fascination of Graham Greene, who based a character on him in Our Man in Havana. In the book, Superman performs at the San Francisco brothel, but Greene had seen him at the Shanghai. In 1960, shortly after Castro took power and during the filming of the screen adaption of the book, Greene tried in vain to find Superman, who had by then disappeared.

A fictionalized Superman also appears as a character in the Godfather Part II, during a pivotal scene in which Michael Corleone, played by Al Pacino, learns of his brother Fredo’s betrayal of the family. During the scene, Superman appears on stage wearing a large red cape. Just as he pulls the cape open to reveal himself, the camera cuts to the gasping audience. Senator Geary: “I don’t believe it, that thing’s gotta be a fake.” Fredo: “That ain’t no fake. That’s real. That’s why they call him Superman.”

Many years after the film was released, the actor Robert Duvall, who starred as Don Corleone’s lawyer in The Godfather, traveled to Havana. Ciro Bianchi Ross, a Cuban journalist who accompanied Duvall during his stay, writes in the Cuban journal Juventud Rebelde that Duvall asked to visit the Teatro Shanghai during his trip. Bianchi Ross told him the club no longer existed, but Duvall said it didn’t matter—he was happy even to see the space where it had once existed.

Among the many nicknames for Superman, we kept hearing a less expected moniker: Enrique la Reina. Enrique the Queen. “I interviewed a couple people who performed at Shanghai, and they said categorically that Superman was gay,” Prieto told us. According to Lowinger’s account, Marlon Brando once asked to meet Superman during one of his visits to Havana, arriving at the Shanghai with two showgirls on his arms. After the performance, Brando, who was bisexual, took off with Superman, ditching the dancers.

Roberto Gacio also believes that Superman was gay and that the rumor about the affair with Brando is true. For Gacio, the performer’s sexual orientation suggests an undercurrent of sadness to his story. There could have been no pleasure derived from the performance. It was all an act, all for the entertainment of the audience. “This was his skill. It was his job,” Gacio said. “He earned his living with his body, not his mind. He had a great treasure.”

A Cuban documentary filmmaker Mike and I had met in New York introduced us to his uncle, Willy, who would show us around. Willy was a 52-year-old gourmand and Lothario, a man-about-town in Havana who seemed to know everyone. He had an astonishing appetite for women; during our ten-day trip, he frequently slipped away for salty rendezvous back at his apartment. A thin man with a well-groomed peppery goatee and an earring, Willy agreed to act as our fixer—all we had to do was buy his meals and drinks.

We met Willy at El Floridita, in Habana Viejo, a bar famous in 1950s Havana. It was heaving with tourists drinking daiquiris when we arrived after dinner. They posed for photos with a bronze statue of Hemingway, who had been a regular here during its heyday. “I hate this place,” Willy said. “This place is like Times Square.”

Willy said he had some intel on Superman. He knew a guy who knew a guy who knew Superman. “Superman was known as the ‘Queen of Italy.’ But if you called him the Queen, he’d punch you,” Willy said. Why Italy? Willy didn’t know, but he said we could meet the man who passed on that information.

The contact was a journalist named Rolando who had written several books on Havana neighborhoods. Rolando also worked as a podiatrist to supplement his income; Willy had arranged a meeting the next morning at this podiatry office. Rolando had also told Willy he knew where Superman had once lived—a neighborhood called Bario de los Sitios, next to a church. It was the same neighborhood Prieto had mentioned. Willy said he thought he knew the block, and he also knew an old lady who lived there. We’d go there tomorrow. Follow la pista.

Rolando, the journalist/podiatrist, lived on a block in Old Havana, just off one of the tourist-heavy streets. He was 71-years-old and wore a white doctor’s coat over jeans and sandals. He had one of those old-man smiles that completely concealed his front teeth, and a bushel of white nose hairs.

His podiatry office was next door to his home. Mike and I sat in the dusty, dimly lit waiting room while Rolando worked in the back room, smoking a cigar, investigating a patient’s bunions.

We were to meet a man named Eduardo, a friend of Superman’s. It was 10 a.m. and we had already been waiting for half an hour. Rolando told us to wait a little longer; Eduardo would arrive soon. The air inside the waiting room was stuffy and smelled of mothballs. Outside, the street was alive with morning activity.

After an hour of waiting, Rolando emerged from the bunion treatment to break the bad news: He’d just spoken to Eduardo over the phone, and he wasn’t coming. “He doesn’t want to talk. He doesn’t want a photo. He’s afraid.”

We offered to disguise Eduardo’s identity, to no avail. We’d already hit a wall in la pista.

Thwarted, Willy led us on a trek across town to find Superman’s home. We walked down bustling commercial streets and through crowded parks, until we reached an alley where a group of drunks played checkers with bottle caps on a piece of cardboard. Soon we arrived on St. Nicolas Street, across from Judas Tadeo church. There was a small market selling meat, flowers, and liquor. Children played outside the church.

Willy rang a buzzer and hollered up to an old apartment with an overhanging balcony. A few minutes later an elderly black woman wearing a purple scarf over white hair emerged from the second-floor window. She looked confused, but then recognized Willy. “Hola. Hola.” She invited us upstairs.

Her name was Gladis Castaneda, and she had been a professional classical pianist in Havana during the 1950s. She was a tiny woman in her eighties or nineties. We entered her spacious apartment, and Willy explained what we were doing. She nodded with he mentioned “La Reina.” Yes, she said, he’d lived in this neighborhood, right next door. Here, in the flesh, was a person who knew the legendary Superman—proof, in fact, that the man actually existed.

Superman, Castaneda said, was tall, strong, respected. “Everyone knew him as the Queen,” she said. “He was gay, but you didn’t mess with him.” She asked me to stand. “He was your height. But strong. Muscular.” He had skin like hers; dark, but not very. “He was a good man. Nobody had a problem with him.” I asked if everybody in the neighborhood knew what he did for a living. “Young man, it was many years ago. He left many years ago.”

Willy asked if she knew what became of him, and she said she thinks he died in Miami. Her energy was waning and Willy nodded to me to suggest it was time we go.

Down on the street, we met an old man leaning against the wall. His name was Elado; he carried a cane and wore a loose green sweater with and Masonic symbol hanging form a chain around his neck. Willy told him we were looking for information on the man they called La Reina.

“Si, si,” the old man said. “La Reina—everybody knew him. Mulatto. About your height,” he nodded in my direction. “Everybody respected him. He lived here for twenty years. Of course, everybody knew what he did for a living.” He said Superman left for the U.S. in 1959. “Nobody knew his name. Everybody just called him La Reina.”

We said goodbye and as we walked away, Elado said: “He was a tremendous mulatto.”

Down the street by the church, roosters crowed. A girl wearing rollerblades talked on a pay phone. An old man in a leather golf cap smoked a cigar on a backless wooden chair.

We walked through Los Sitios toward Barrio Chino, until we arrived at 507 Marquis Street. We stood on the street looking at the entrance to a martial arts school: Escuela Cubana Wushu. It had a red and yellow façade with a gold Fu dog and a yellow iron gate.

This was once the home of the Shanghai Theater.

The door was open. Inside the front gate was a courtyard with a small café and some stationary exercise equipment. The Shanghai Theater once stood where the school’s outdoor courtyard is now. We tried to imagine where the stage might have been. The dressing room where Superman prepared for the show. The balcony from where drunken tourists watched the performance.

Mike said, “You can almost smell Superman’s sweat.”

A few days later, we returned to El Barrio de los Sitios to canvas for others who might have known Superman. In the apartment building next to Gladis Castaneda’s, we met Superman’s actual neighbor: a former pizza chef named Roberto Cabarero, 82-years-old, with a heavily stained and stretched muscle shirt, drooping brown pants with the fly wide open, and black socks with holes in the toes. His hair was white and wild. His skin sagged like a sea turtle’s.

Cabarero’s apartment, where he lived with his wife, was tiny and ramshackle, littered with junk. His wife sat in the middle of the small living room, rocking back and forth in a wooden chair, talking loudly at no one in particular. A radio blared tinny old Spanish songs, and a dog came in and out of the room to eat crumbs off the floor. An alarm clock sounded during the duration of our meeting, and no one bothered to turn it off.

Yes, he knew Superman. “Siiiiii!” He told us Superman’s name was Eve Solis—I looked at Willy, who shook his head and whispered, “‘Eve’ isn’t a Cuban name”—but he was known as Enrique la Reina. He rattled off facts: Superman was born on April 24, 1920. Everyone knew he was gay. He was more than six feet tall.

Cabarero had lived in this apartment since 1952, and he remembered Superman hosting wild parties next door. He said Superman often associated with foreigners and may have practiced Santeria, the syncretic religion that grew out of the slave trade in Cuba.

Cabarero spoke as if he were performing a Shakespearean soliloquy, with enthusiastic, swinging hand gestures. The radio blared; the alarm clock rang. His wife, in the rocking chair, began telling a story that made no sense whatsoever.

Cabarero went on, speaking over his wife: “This is La Reina’s chair!” He grabbed hold of the top of the rocking chair his wife is sitting in, without offering an explanation about how he came by the chair.

He then broke into a long and somewhat difficult to follow anecdote about his famous neighbor: One night Cabarero and his wife went downstairs to the street with their daughter. There, they found a man urinating in the street. A confrontation occurred. Then Superman appeared, wielding a knife, and chased the man away. “You have to respect my neighborhood!” Superman screamed at the man, according to Cabarero’s recollection.

Cabarero wrapped up the story: “I don’t care if you’re writing something good or bad, this guy was a good guy.”

I asked what happened to Superman, and he said he might have seen him once or twice in Havana in the early 1980s, but he didn’t know for sure where he died. As he spoke his wife shouted in the background, and the alarm clock continued to ring.

There is a sense, to those with an eye for nostalgia, that the 1950s never died in Cuba. In Havana, you see young men with greased hair piled into old cars, arms out the windows like in American Graffiti or West Side Story. You can see also what the city might become if it opens the door to American tourism too eagerly. One day not far off city tours will make stops in Old Havana, escorted in 1950s Chevys. Passengers will wear fedoras and chew cigars with an annoying relish. The old hotels will host gangster-themed parties and ironic 1950s beauty pageants and offer discount stays in the “Meyer Lansky Suit.” Havana will become a Disneyfied version of its former self: glamor, sex, and sin, only without the actual glamor, sex, and sin.

As Cuba continues to open, the country will be forced to consider its post-Castro identity. There is the threat of Cancunization, as Prieto mentioned: an economy based on tourism developed with little concern for the local population or environment. But Cuba’s future is more complicated than that, and it will forever be shaded by the past. In the American imagination, Cuba has always been exoticized as the hot, humid, sexy, torrid whorehouse of the Caribbean. It was an identity imposed upon the people, much like Castro imposed a national identity of brothers-in-arms socialists. In the years to come, how will Cubans get beyond these two notions of itself, both of which are too easy, too simplistic, and develop a new identity for the 21st Century? Will Cubans be defined on American terms, on Castro’s, or on their own?

Race is a huge part of that question. Pre-revolutionary Cuba was a place of deep, systemic racism, which the revolution promised to change. In communist Cuba, all citizens were literate, regardless of race, and employment opportunities improved greatly for people of color whose main source of employment had been the sugarcane fields. Life expectancy was increased for nonwhites and access to health services, nutrition, and education improved.

But racism remained, concealed mostly because it wasn’t discussed. White Cubans dominated the revolution, and dark skin continued to be associated with negative social and cultural traits. Twice as many blacks were unemployed as whites, and whites dominated positions in Cuba’s top universities. Eighty-five percent of the country’s prisoners were people of color. Today, black and mixed-heritage people make up close to two-thirds of the population, and race remains a complicated issue. The term “mulatto” is used both in casual conversation and in official government documents. The kind of racially-charged sex show that Superman starred in doesn’t exist in Havana today, but it might if Cuba becomes not just freer and more libertine but also more unrestrainedly racist in the future.

Similar discussions will be had over sexual orientation. As of 1979 being gay was no longer a crime in Cuba, and in recent decades, the country has come a long way from the 1960s and 1970s when gays were thrown into labor camps. Mariela Castro, Raúl’s daughter, is the director of the state-run National Center for Sex Education and a leading voice for LGBT rights. She has been promoting public tolerance for the LGBT community since 2004 and persuaded the government to offer fully paid gender reassignment surgery and hormone treatment for transgender people. She also voted against a labor code that protected gays and lesbians, but not transgender people, arguing for full equality under the law.

But discrimination persists. Havana does not recognize Pride Week, the international celebration of LGBT rights, and “publicly manifested” homosexuality remains illegal under the country’s penal code, which also forbids “persistently bothering others with homosexual amorous advances.” Same sex unions continue to be barred in the country.

The ease with which Superman’s pre-revolutionary neighborhood seemed to accept his sexuality seems at odds with the revolution’s treatment of gays. And after the revolution? What kind of life would a man like Superman be able to lead in post-Castro Cuba? What kind of work would he find? Would his life be a “melancholy demonstration,” to borrow Stone’s words, of the return of Cuban inequality?

We continued to follow la pista, only it seemed to be leading nowhere. We met the son of the former mayor of Los Sitios, a dapper gentlemen with slicked back white hair named Rafael Diaz Valez, who delighted us with tales of his youth during Havana’s glory days, but got us no closer to knowing the real Superman. We asked him and everyone we met if they knew of any showgirls, any bar or cabaret workers who might have actually known Superman, and they all said they didn’t. We met historians and musicians and dancers—none of them got us any closer to unraveling the story of Superman.

One day Mike and I went to the Cementerio de Cristóbal Colón, the resting place of centuries of Havana’s dead. The sky was dark and a storm was about to break. We went to the administration offices and asked if it was possible to search the archives. A woman at the desk told us we might be able to find Superman’s grave, but only if we had a full name and date of death. We gave her two names—Eve Solis, and Enrique Solis—but no date of death. The woman disappeared into a room for ten or fifteen minutes, but she found no one with those names.

Our last night in Havana, we bought tickets to the show at the Tropicana Club, an outdoor theater in the suburbs, open air, under the stars and enormous trees. Middle-aged tourists were bussed in from the all-inclusives in Varadero or the refurbished hotels in Old Havana. The show was the same as it’s always been: beautiful, scantily clad women; men in baggy black suits belting old show tunes in Spanish. We drank rum on ice from our table in the front row.

Here it was already: The Havana of yesteryear, the Havana of tomorrow.

Back in New York, we set Superman aside. Every once in a while I would email Alberto Prieto and we would update each another on our respective searches. We contacted a few more potential sources, but always came up empty handed. The story of Superman—who he was, what became of him—remained elusive.

In the absence of the latticework of a life, Mike and I filled in the blanks ourselves. We pictured Superman as a tragic figure, more freak show than performer. A man whose natural gift doomed him to a life in an unhappy spotlight, under the gawking stares of a bunch of drunk, rich Americans. The movie of Superman’s life played in our minds, even if we weren’t exactly sure of the plot.

There was one last lead, one that in the months after our trip had slipped our minds. When we met Prieto in Havana, he told us about an attorney named Frank Ragano who represented many of the mafia elements operating in Cuba in the 1950s. In his memoir, Mob Lawyer, Ragano, who died in 1998, wrote of a night in Havana with Santo Trafficante, Jr., the Florida mob boss. Trafficante had hired Superman—who is referred to as El Toro, “The Bull,” in the book—for a private sex show. “According to a popular joke,” Ragano writes, Superman “was better known than President Batista.”

The viewing took place in a small room with couches around a platform stage and mirrors. Paintings of nude men and women plastered the walls. A hostess clapped her hand and then entered Superman and a woman, both naked. He describes “El Toro” as being in his mid-thirties, about six feet tall, “and average-looking except for his genitalia.” (Trafficante said it was 14 inches.) The two performers “engaged each other for thirty minutes in every conceivable and contorted position possible and concluded with oral sex.”

Ragano was also a home video buff and asked if he could film a second performance. Trafficante obtained Superman’s permission, and Ragano then filmed what he believed to be the only known footage of the man. He then chatted with Superman, who told him he was paid $25 a night for his efforts. “You come to Miami,” Ragano told him, “I’ll get you a pair of those loose, short shorts. We’ll walk up and down the beach in front of the hotels. I guarantee you that you’ll end up owning one of the big hotels.”

I found the Tampa law office of Chris Ragano, divorce attorney and the son of Frank Ragano, through a Google search. After a few calls, I was able to get the younger Ragano on the phone. I told him I had a somewhat unusual request: Did he happen to have a copy of his father’s video of El Toro, a.k.a. Superman?

Ragano laughed. He said he did have a copy, in fact, and he would find a way to get it to me. He also told me his mother, Nancy, might have an idea about what happened to Superman after the revolution.

Nancy Grandoff was Frank Ragano’s second wife. She was a much younger than her husband, and though she didn’t accompany Frank on his trips to Cuba, she did meet some of his associates from that time, including the mobster Santo Trafficante, Jr., who was an occasional visitor to the couple’s Florida home.

“He and Santo would laugh and talk about Superman,” she told me when I spoke to her on the phone. “They always laughed about it. They still couldn’t believe he was who he was.”

She watched the video once. “I knew my husband had the video and I had some girlfriends over and I asked my husband to put the video on. He laughed, and we laughed too after a glass or two of wine. It’s an amateur video. You can hear it run. Superman himself, he was a big man. I think that’s the only way to describe him. Santo said Superman wouldn’t allow photos or videos. So this video was a favor to Santo for Frank Ragano.”

Grandoff heard about Superman’s fate around 1966. Rumors had been circulating on the Cubans-in-exile grapevine that Superman—El Toro, La Reina, the Man With the Sleepy Eyes—had died. During one visit, Frank Ragano asked Trafficante if the rumors were true, and Trafficante confirmed them: Superman had fled from Cuba to Mexico, where he was trying to escape to the United States. In Mexico City, Trafficante said, Superman was murdered by a jealous lover. And that’s all anyone knew.

In the years after Cuba fell to Castro, Frank Ragano, Santo Trafficante, and the others often waxed nostalgic about those years in Havana. The good times. An era of movie stars and gangsters, of sex and Superman.

“I remember asking a friend, ‘Was he real?’ And she said, ‘Oh yes, he was very big,’” Grandoff told me. “Every time the Americans would go for the weekend, the first thing they wanted to do was buy a ticket to see the Superman Show.”

A few months later, an email from one of Ragano’s associates arrived. “The video is up for your viewing,” the note read.

Mike and I met at his apartment in New York. We poured two glasses of whiskey and watched the strangest historical artifact ever to cross our eyes.

The video is black and white, grainy. Fast-paced, grandiose music plays—like the score of an epic from the 1970s, maybe Lawrence of Arabia. A blond woman stands before the camera. She’s white, naked with dark pubic hair. She wears a shy smile on her face.

Superman appears to the left of the frame. He’s black, his hair grown out somewhat. There’s barely a glimpse of his face. He’s thin, sinewy, naked except for black socks. His penis is flaccid; he pulls at it, trying to get it to perform. Once erect, you can see how the legend was made. It’s large—maybe not 18 inches, but a good twelve—and at one point he stands sideways to the camera, hands on his hips, so the audience members can gauge just how large it is.

And then the two have sex. There’s no ceremony to this. No performance. Superman is wearing no cape. Neither of them is exhibiting any joy. This is pornography only, two people being paid to have intercourse for the entertainment of others. They perform oral sex on one another, and engage in a number of different positions. Neither achieves orgasm.

We sit in an odd silence when the video ends, not entirely sure what to make of it all. This grainy video is the end of la pista in the search for Superman. And there at the end we find no legend, no ghost. There we simply find a man. A man with a machete, and nothing more.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified Rosa Lowinger. She is the author of Tropicana Nights and an art conservator.

Michael Magers is a documentary photographer based in New York.