The strange, seedy, surprising world of England’s dreary coast.

In England, whatever is too strange for the everyday world, and whoever is too eccentric, ends up by the sea. They all come to the shore: con-artists and dreamers, snail-trainers and Elvis impersonators, even Coco Chanel, who, it is said, landed her seaplane in the surf at Morecambe Bay.

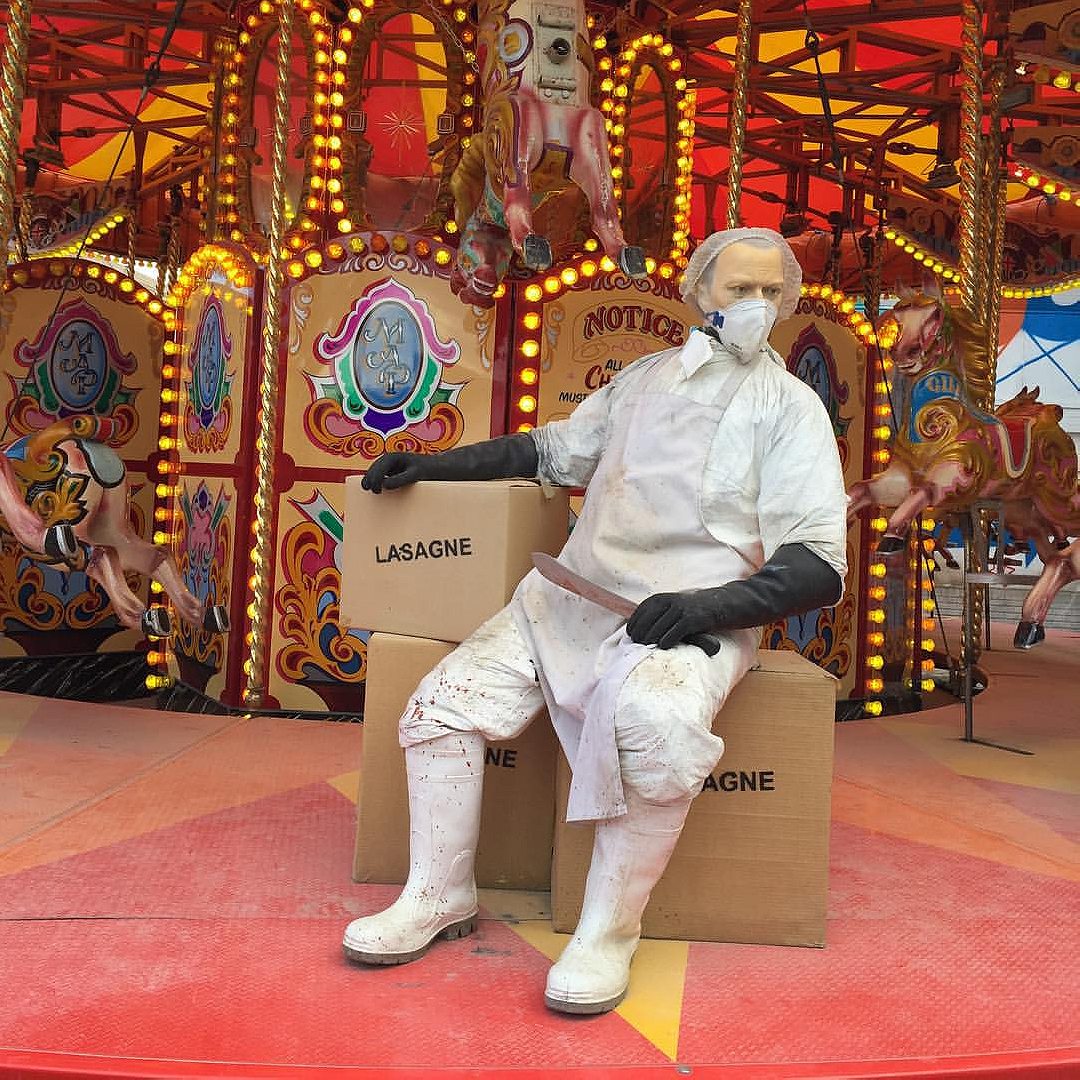

Most recently, British artist Banksy’s bizarro theme park, Dismaland, took over an abandoned swimming pool in the seaside town of Weston-super-Mare. At the top of the concrete perimeter wall, fairy lights were strung like barbed wire. Wrapped up in hoodies, their faces invisible, the guards watched like zombies. The wind picked up. People waiting to get inside took pictures of the waiting crowds in which they found themselves. “If you die of boredom, they’ll let you in and make you part of the show,” someone told me. Music from The Big Lebowski and creepy children’s voices drifted over the wall.

Here in Weston-super-Mare, the sea can be hard to find. Stand on the beach and there it is in the distance, but between it and you, acre after acre of glistening ground stretches out, hemmed in by yellow warning signs: “Danger. Sinking Mud.” With no sea to offer, the good people of Weston constructed a vast open-air swimming pool on the shore. They built it of brutal gray stone with some Art Deco flourishes and optimistically called it the Tropicana. It has long since closed its doors in despair. For years, it has been plastered with posters announcing one failed development after another. This summer, it became Dismaland. With its burned-out castle, decaying exhibits and endless lines, the park is a study in disappointment. But don’t be taken in by the pandering peculiarity: Dismaland is one of the less weird parts of the English coast.

England may not have any abandoned temples in windswept deserts, “vast and trunkless legs of stone” and the misplaced pride of Ozymandias, but it still has its epic follies: places where grand ambition had free rein, at least for a while.

Visit them today, and you can see the high-water mark, the glorious moment followed by inevitable decline. Weston is one such place: its Grand Pier is awash with wrought-iron latticework, towers, and domes. The wonders of the world were to be gathered here, for Weston to delight in them, and they in Weston. Today, it is almost empty, an abandoned palace floating above the mud.

Even Bill Bryson got depressed here

The desolation of the English coast is hard to ignore. Paul Theroux’s Kingdom by the Sea spoke of fetid food, gray skies, and skinheads. Weston, a plywood Xanadu long past its prime, is hard to love. Even Bill Bryson got depressed here. “I had just passed,” he wrote in Notes From A Small Island, “the dreariest evening of my life in this God-forsaken hellhole of a resort.”

But look past the battered surface of the English seaside, and curious things appear. For decades, people who couldn’t survive elsewhere have thrived in the strange, seedy world that clings to the shore. And traces of their lives are everywhere.

Weston is a town built by dreamers, some more successful than others. In 1891, W. Randolph Varney set up his Electric Life Invigorator Company here, promising to treat holiday-makers for “muscular relaxation, genital derangements, impotence, and loss of virile power.” “No Great Deeds,” Varney warned his customers, “were ever accomplished, discoveries made, or inventions completed by the man who is sexually bankrupt.”

Victorian doctors, con artists, and peddlers of dubious products (“Erasmus Wilson’s Formula for Whiskers”) flocked to Weston. Varney was particularly relentless, writing: “It may be interesting to those who are seeking a Healthy Resort to learn that Weston-super-Mare stands absolutely the first in point of healthiness, the death rate being lower than any other English watering place.”

And then there’s Herbert Whitley. In 1904, he moved to Paignton, on the coast of Devon, and began to assemble one of the strangest collections of animals in the world. When London Zoo wanted a particularly rare specimen—a mysterious Peruvian rodent, perhaps, or a nameless spider—it often turned to his menagerie-by-the-sea, housed at Primley House, on the edge of town. Crates and cages by the dozen descended on Paignton from all over the world, slung into the baggage-vans of trains, their inhabitants hissing and roaring and gibbering. Paignton was a miniature outpost of English respectability gone mad: its Gleneagles Hotel was the model for Fawlty Towers, John Cleese’s sitcom about the least hospitable hotelier in England. One can only imagine what its proprietor thought of Whitley.

Today, monkeys and crocodiles greet travelers at Paignton station, splashed over the walls in bright murals. The town is proud of its little piece of the exotic. Wistful retirees found their way here from every corner of the British Empire and built their villas to resemble the clifftop palaces of India. Crumbling pillars peep incongruously above the trees. And outside the town, Primley House lurks with its crocodile ponds.

There is no such thing as a polite camel

Closest to town are the camels. The distance between suburban house and camel backside is little more than fifteen feet. They are Bactrian camels: fat, molting, and malevolent, like walking wigs. They leer disconcertingly into the windows of the houses. There is no such thing as a polite camel.

Today the zoo is a serene place, but in Whitley’s time, accidents were known to happen. When each successive round of chaos threatened to engulf the zoo, he was apt to murmur, “Ah … that’s awkward.” He did not approve of fluster. When, one day, a worried-looking maid came running in to see him, he took his time before looking up. “Sir,” she said, all in a rush, “the railway station’s on the telephone and they say there’s two lions and a tiger just arrived for you, and one of them’s getting out.”

Whitley often ordered animals, and then forgot they were due to arrive. This was such a case.

“Ah, that’s awkward,” he said, after awhile. “We haven’t finished the Lion House.”

Getting all these creatures to Paignton was not exactly simple. Shipping woolly-necked storks by the Great Western Railway required a special form. Customs duties had to be paid on the tiger. And there was the small matter of the Parrot Permits. The zoo’s archives—kept in a giant shed—are stacked with letters from confused officials. By and large, the railway staff coped rather well—and chose the far end of the platform to offload the iron-bound packing cases marked “H. Whitley” as oblivious holiday-makers streamed by.

Whitley’s zoo should never have succeeded. Yet, it was acknowledged to be one of the finest in the world, and today, long after Whitley’s death, it remains an important center of conservation. It survived thanks to its owner’s knack for improvisation, and thrived on his steady passion for every last hairy spider. He would wander through the menagerie late at night, attentive only to the soft hoots and snores around him, wondering, sometimes, if his lions would escape before dawn.

Even the drabbest surroundings can conceal weirdness and wonder. If you walked down the street in Paignton in 1964, for instance, past department stores and bakeries piled high with cakes, you would never guess that “England’s number-one woman burglar” (as she called herself) was hiding out around the corner.

Zoe Progl was vain, glamorous, and brilliant, though unlucky in her choice of accomplices. In 1964 she became the first woman to break out of London’s notorious Holloway Prison, grazing her bottom on the barbed wire and hopping into a waiting car. She decamped to a caravan in Paignton, and lived with quiet delight, “taking snaps, basking in the sun,” with an iron bar behind the door to thump any unwanted visitors. Arrested at last, stark naked in the middle of the night, she was driven back to prison dressed in a mink coat and diamond-studded bracelets.

The greatest of England’s seaside fantasies was the Royal Pavilion, in Brighton. Today, Brighton is a gentle place of coffee and kale, Portlandia by the sea. But it was once the most fashionable and extravagant town in the world. At its heart sits the Pavilion, a sand-colored Indian palace plucked from the world of imagination. Busybody nineteenth-century England rustled with Oriental fantasy, and the Pavilion embodied all that forbidden allure. The Orient of the nineteenth century was not the sweet stuff of Disney, but a place of darkness and wonder, of mysterious enchanters and sex-starved genii.

Built at the behest of George IV, then Prince Regent, the Pavilion was once the magical heart of England. From his lilac-silk bed, topped with swan’s-down blankets, and surrounded by fearsome dragons and fairytale birds made of precious stones, George oversaw the greatest debauches the country had ever seen.

Yet even such delights as the Regent’s faded. For all his bravado, he was forced to marry the unappealing Caroline of Brunswick in exchange for having his elephantine debts repaid by Parliament.

But that is the fairytale’s trick. It makes you wait long past hope. After the Regent’s splendor had faded away, in the middle of the First World War, Brighton’s Pavilion looked sadly misplaced. Like Weston’s Tropicana today, it was an abandoned pleasure dome from a time long past. One day, that changed. In France and Belgium, thousands of Indian soldiers were fighting for Britain. Many were wounded and in need of convalescence. The men from the War Office remembered a shape at the back of their memories, the closest they had ever come to the fabulous Orient.

The Pavilion was promptly turned into the grandest hospital in the world. Ranks of beds full of soldiers were set below the domes and chandeliers. The kitchens were stocked with heaps of imported spices, dhal, and ghee. The King and Queen came to visit—the guests of an Indian hospital, not the proprietors of a British palace—and awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest honor, to Mir Dast, who had carried eight Indian and British soldiers to safety, one by one, through the nightmares of the Battle of Ypres. All of a sudden, there really was an Eastern palace on the Brighton seafront.

But England is not always kind to optimists. Beside the sea, the pitchman’s bright smile can tip over into desperation. The hotels are too unforgiving. The rain is too persistent. The piers are too apt to catch fire. Even Billy Butlin, who built an empire of seaside resorts marked by their grinding cheerfulness, could not forget a childhood holiday on the shore: “When it rained life became a misery. And it rained incessantly.” When King George V’s doctor suggested sea air and a trip to Bognor Regis, His Majesty was succinct if nothing else: “Bugger Bognor.”

In Weston, I sheltered from the rain in a fading hotel, amid elderly guests and last week’s newspapers. Victorian authors spoke with horror of the food in seaside hotels. “The dinner,” remarked one guest in Brighton, “was very bad; a sprawling bit of bacon upon a bed of greens; two gigantic antediluvian fowls, bedaubed with parsley and butter; a brace of soles that perished from original inability to flounder into the ark, and the fossil remains of a dead sirloin of beef.” (It is a mistake to think that the English do not complain. They grumble as compulsively as they queue.) In Weston, the hot chocolate tasted like dishwater.

Weston had hope, this summer. But Dismaland came and went, and now, the crowds are fading once more, and the wind is sharp along the muddy shore. (The park’s relics have, improbably, been promised to a refugee camp in Calais, France.) One gray day looks much like any other. It will take more than Banksy’s fairytale castle to rewrite Weston’s story. Yet for a time, this summer, it was again a place unlike any other.

[Cover image: The Grand Pier, Weston-super-Mare. Photo: Edmund Richardson Webster]