What a storytelling festival in Edinburgh can teach you about Scotland’s past and future.

Let me tell you the tale of a man neither good nor bad, but both at the same time. Let me tell you about a man whose story, some say, never ended. Let me tell you the story of Deacon Brodie.

With that, the old man rasps from the back of his clogged throat. His Scottish accent lies heavily on each syllable and he whistles through his sibilance. At the end of a key point he freezes into an expression of disbelief and glances faux-wistfully into the distance. He holds this position for an unnaturally protracted period, allowing his listeners just enough time to think he has lost his way. But then, before any true awkwardness settles in, he whips his arm, bangs his heavy cane, and continues, running through words and hurdling over punctuation, until he stops, exactly as he did before, seemingly mesmerized by his own story.

Dressed in 18th century attire—hat, long-tailed coat, frilly shirt, long socks and buttoned-up trousers—he cuts a mildly ridiculous figure, but is seemingly unaware of own his melodrama and the frayed ends of his cheap costume. He holds forth reflexively, convincing the audience of the narrative’s strength through his enthusiasm.

And then, in a final wheeze—a final creaking, shaking bend of the knees—the story of the life and death of Deacon Brodie, one of Edinburgh’s most infamous hypocrites and the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, is over. Jack Martin, renowned storyteller, doffs his hat, bows, and then returns his hands smartly to the pockets of his waistcoat. He smiles a satisfied smile. A gaggle of Swedish girls dashes to take a selfie with him while the rest of the small audience applauds.

I am at the 10-day-long Scottish Storytelling Festival in a cramped attic room on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. And that was “Deacon Brodie Unmasked,” an hour-long investigation of Edinburgh’s 18th century city councillor-cum-boozing-bank robber, William Brodie.

The festival is based on the Scottish Ceilidh—a traditional social gathering—and celebrates and investigates Scottish culture through storytelling. The organizers put on events throughout Scotland, but the festival’s home is Edinburgh, where the country’s most famous stories were born.

The festival’s headquarters occupy part of the John Knox House, one of the oldest buildings in Edinburgh. It is here, in a bustling little café, that I meet Donald Smith, the director of the Scottish Storytelling Centre and festival. Wearing a tweed blazer and thick professorial glasses, Smith has a crisp voice and a deliberate diction.

“The festival is 25 years old and is about exploring the role of storytelling traditions of all kinds in contemporary culture,” he says. “However, it is deeply linked with the re-emergence, within the past 35 years or so, of a Scottish national consciousness.”

Smith, like many writers and artists here, is a fervent believer in Scotland’s right to independence. But he isn’t using the festival as propaganda for the Scottish National Party (SNP). “I am a believer in independence, of course,” he says, “but I am not affiliated with any political party and nor am I using this to forward political aims.”

Nor is he trying to salvage some tartan-patterned conception of Scottish Identity. The point of the festival, according to Smith, is to provide resources through which people can investigate their national identity. Indeed, it was this sentiment that had attracted me to the festival in the first place. Yes, I had come to learn about my country’s folklore, but I had also come to find out how these stories had affected our sense of Scotland as a nation. And how, in the aftermath of last year’s failed referendum on Scottish independence, storytelling may shape the country’s future.

Edinburgh’s storytelling tradition is rich; it is the birthplace of many writers, poets, and sinister tales. It is where Sir Walter Scott set The Heart of Mid-Lothian; where Dickens misread the tombstone that gave him the inspiration for A Christmas Carol’s Ebenezer Scrooge (the corn merchant’s tombstone read “Ebeneezer Scroggie, Meal Man,” which Dickens misread as “Mean Man”); and where J.K Rowling, gazing at the fairy-tale towers of George Heriot’s School, was inspired to write the Harry Potter series.

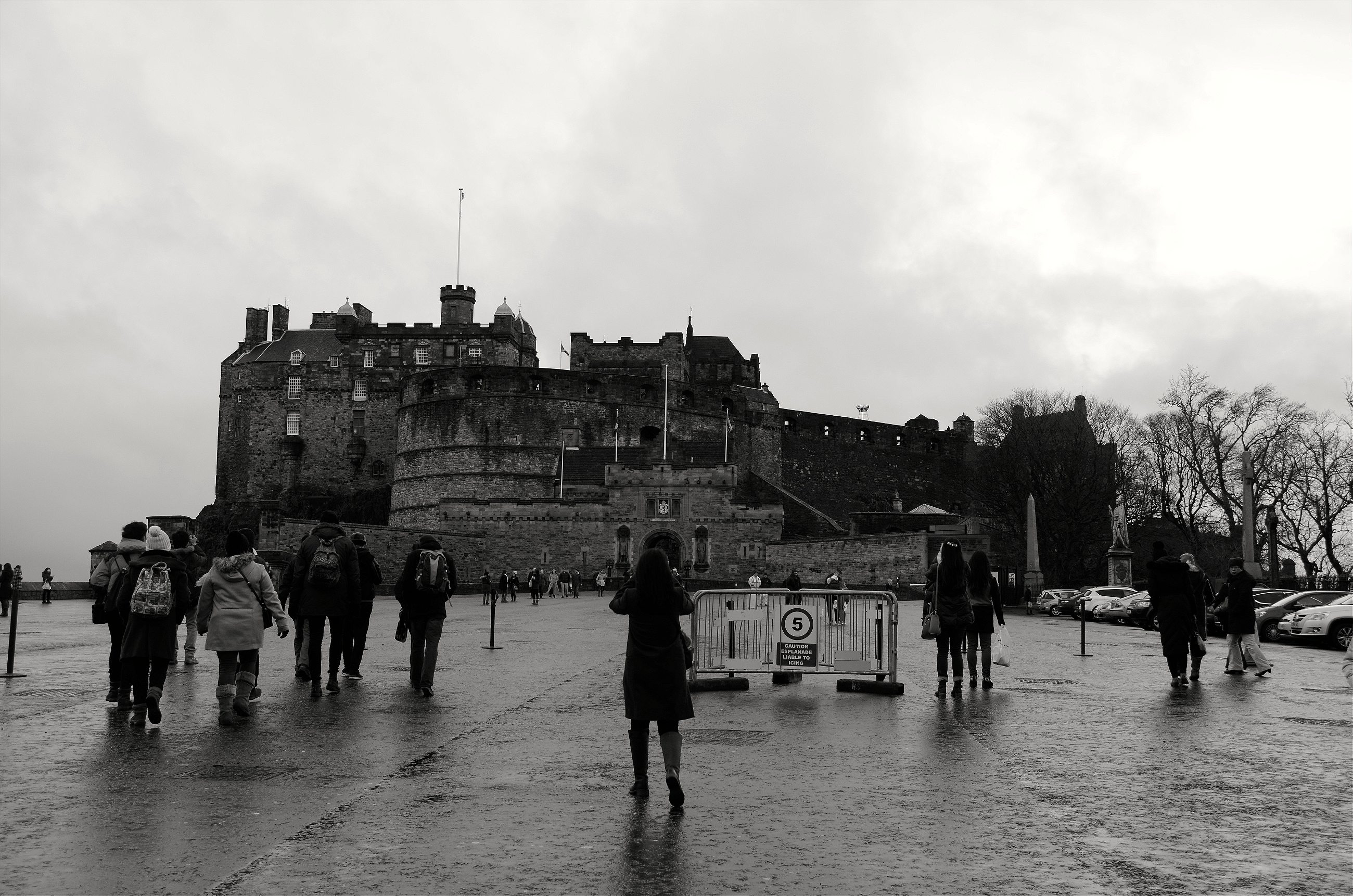

Perhaps the most iconic part of the city, the neighborhood where tourists flock and to which Scotland’s political and literary history clings tightest, is the Old Town. The Old Town was built on a ridge formed in the last Ice Age when receding glaciers were split by harder volcanic rock. It was on the summit of this ridge that King David I of Scotland chose to build his great medieval fortress in the 12th century. Today, this is where the city’s iconic castle, destroyed and rebuilt many times since the days of David I, towers over the New Town.

During the Wars of Independence in the 13th and 14th centuries, English raids largely destroyed the city. At the end of these hostilities, however, a bustling city of commerce emerged, dominated by high-rise buildings and narrow passageways that ran like mercantile streams from the city center. In the 15th and 16th centuries, tourists would come to gawp at the gothic architecture and the world’s first skyscrapers.

Of course, the Old Town wasn’t all innovation and grandeur. From the end of the 16th century to the beginning of the 18th, Edinburgh’s population increased six-fold, without any great increase in the size of the city itself. Indeed, at one point, over 40,000 people were crammed into just 140 acres of sodden Scottish earth. The city was congested, smoggy, and disease-ridden. Rampant fires cut through its towering tenements, choked its residents, and destroyed many of its buildings.

On the Castlehill, where the unswerving stretch of the Royal Mile begins, the street-facing buildings lurch in and out of the shadows, while others huddle in courtyards and squeeze into the city’s grudging closes (the Scottish term for an alleyway). In these closes—where tourists are less prevalent and the volume of synthetic piper-pop is lower—you get a real sense of the old squalid scramble of the city. The capital’s identity as Auld Reekie, for its thick smog and stench, still lies heavily in these less frequented corners.

From the weathered steps of Gladstone’s Land, a 17th century tenement house and the stage for Martin’s performance, the Lawnmarket stretches out onto the Royal Mile. Here, tourists chatter, chortle, buy, and bump into one another in a mass of guidebooks and checklist consumption. Irritated locals look for shortcuts, duck out of photos, and keep their eyes to the slippery cobbled streets. The rain whips through the closes and dribbles down the narrow faces of the houses. It’s a dreich day in Edinburgh.

Moving past these crowds, I wander in the direction of the festival’s headquarters. On the way, beside the gothic hulk of St. Giles’ Cathedral, five boisterous men jostle around the Heart-of-Midlothian, an old mosaic made from granite setts. One of them kicks at the saliva and lumpy, petrified chewing gum that sits on its surface. The others hawk up their own contributions as they laugh and take pictures of their flying phlegm. This was the site of the old Tolbooth prison, one of Edinburgh’s most notorious penitentiaries. Its entrance was traditionally spat on by residents as an act of disdain. Now spitting is just another act of tourism.

It was around here that Deacon Brodie was hanged in 1788 in front of a crowd of 40,000. In his rendition, Martin said Brodie wore a steel collar and inserted a silver tube into his throat to save himself. Some say he died, others say he escaped. Another story, told in Ian Rankin’s novel A Good Hanging, is that criminals who had been sentenced to hang were often given the chance to run the distance of the Royal Mile, a blood-thirsty crowd in pursuit. If the criminal reached the Royal Park before he was caught, he would be allowed to remain in safety, so long as he did not step outside the park’s confines.

Up and down the main body of the Mile, known as the High Street, Edinburgh parodies itself, one continuous stereotype of saccharine Scottishness. Copious cashmere shops, seemingly too many to survive the laws of supply and demand, clog the fronts of buildings. Tourists congregate around kitsch restaurants selling haggis and whisky. Haggard and hypothermic bagpipers are everywhere, their tunes combining to sound like an ambulance’s siren. Budget bards and generic Scottish warriors rove up and down the Royal Mile, leading tourist groups with navigation help from iPads. Where did this kilt-wearing-warrior-Scottishness come from?

A story, of course.

In 1707, in Parliament Hall, surrounded by the Scottish High Courts and the country’s shame, the Scottish government, facing a deteriorating economic position, approved a union with England. Yet, as historian Hugh Trevor Roper notes, “When a society renounces politics, it can find other ways of expressing its identity.” With the relinquishment of its political power, cultural power became the country’s main ideological tool.

Throughout the 18th century, a seemingly endless stream of Scottish academics, inventors, and entrepreneurs poured forth, and Edinburgh became known as the “hotbed of genius.” Renowned figures such as David Hume, Francis Hutcheson, and Adam Smith all burst onto the intellectual scene within a matter of years. By 1750, Scotland’s citizens were among the most literate in Europe: 75 percent of its population could read and write. The country became a bastion of intellect and entrepreneurship within Europe, leading Voltaire to comment that it was to Scotland that the rest of Europe looked for “all ideas of civilization.”

All the country lacked now was a past; something old, coherent and unifying that would enshrine Scottish identity within the Union. And 54 years into its accord with Westminster, Scotland would get just that. Two unrelated men of the same name, James Macpherson, a writer from Ruthven, and John Macpherson, a reverend from the Isle of Skye, forged two works that would recreate the entire history of their country.

In 1761, James Macpherson claimed to have found and translated an epic called “Fingal,” written by the ancient warrior-bard Ossian. In fact, the writer had invented the poet and cobbled together his work from a variety of sources, including a selection of old Irish myths and the works of English writers such as Milton and Shakespeare. Supporting this lie, John Macpherson wrote a critical dissertation in which he provided the historical context for Scotland’s newly discovered poet. He placed the Irish-speaking Celts in Scotland 400 years before their historical arrival, and explained away the native Irish literature as having been stolen in the Dark Ages by the dishonest Irish from the innocent Scots. The Edinburgh literati were blissfully unaware of the story’s provenance and hailed Ossian as the Scottish Homer. Acclaim for Ossian’s work spread internationally: Thomas Jefferson, Napoleon, and Goethe were among his devotees.

The kilt was not a dress of Scottish heritage.

Ironically, it was one of this myth’s critics, who, in denouncing its veracity, created another of the country’s most famous myths. In his 1805 essay decrying the origin of Ossian’s epic, Sir Walter Scott wrote confidently that the Scots of the third century AD wore the “tartan philibeg,” otherwise known as the modern kilt. This was not true: the modern kilt didn’t appear in Scotland until the 18th century and was in actual fact invented by an Englishman. Thomas Rawlinson, a Lancastrian industrialist, had developed the garment from existing local dress for the convenience of his Highland workers who could not afford to buy trousers. The kilt was not a dress of Scottish heritage; it was only made to seem that way by Sir Walter Scott’s relentless romanticism and by its later adoption by the ruling elites as formal Scottish wear. In reality, it was a product of English capitalistic efficiency.

To mention this is not to question the legitimacy of Scottish culture; every nation has its myths. Scotland needed a version of itself that was completely distinct from its more powerful neighbor, and it found this distinctness in the voices and imaginations of its writers. As the award-winning novelist James Robertson tells me, “The reason people revered Walter Scott so much was because he did what people wanted. He gave them back their identity.”

“Old stories never grow old because they are made new every time they are told,” says Ian Stephen, a writer and speaker at the festival. Back at the Scottish Storytelling Centre, I’m listening to Stephen talk about his experiences as a storyteller. “Sometimes you try to change things up a bit, sometimes you feel you want to emphasize one bit more than another, but the story’s never a finished product—it’s always a work-in-progress.”

It is a sentiment that is also true of the Scottish independence narrative over the past 300 years. Stories have been invented and refined, and the national consciousness has become that much clearer; the myths have been updated, so to speak. For example, in 1996, the Scottish National Party aligned itself with the Hollywood blockbuster Braveheart, which tells the story of the heroic William Wallace during the Wars of Independence. During the film’s cinematic release the party distributed leaflets that read:

“TODAY IT’S NOT JUST BRAVEHEARTS WHO CHOOSE INDEPENDENCE – IT’S ALSO WISEHEADS – AND THEY USE THE BALLOT BOX.”

The association was a success, with opinion polls for that year recording an eight-point rise in support for the party. Fast-forward some 18 years, and relatively little was made of the 2014 referendum’s overlap with the 700th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn (perhaps one of Scotland’s greatest victories against English forces). According to James Robertson, a supporter of independence, it was thought crass in light of the open-minded and informed debate taking place in the country. “Recently, I think it is fair to say that discussions of Scotland’s independence have undergone a maturation process,” he says. “The narratives that are being invoked are somewhat more cogent than they once were.”

No longer is it feasible, or convincing, to cast the SNP as a band of tartan-clad peasant farmers fighting against the mightily evil forces of Westminster. This type of Braveheart nationalism has been outgrown.

So where is the story now?

To many, the referendum was meant to constitute the end of this long and complex narrative. After the referendum failed, British Prime Minister David Cameron proudly announced that the debate had been “settled for a generation.” However, this is not the case. Concern over Westminster’s ability to deliver on its devolution promises has caused huge surges of support for the independence movement. “I don’t think any of us are willing to accept no change,” says Stephen. “‘No’ was nothing to celebrate. ‘Yes’ is still an idea.”

And it seems the public agrees. Only a week after the referendum, the SNP gained 35,000 new members. And, according to a poll by the market research firm IPSOS-MORI, the party could win 54 of the 59 available Scottish seats in the upcoming UK parliamentary elections; currently it only has six. As Stuart McHardy, a Scottish historian and independence activist, says, “The referendum was only round one. The process may have several rounds before the resolution is achieved.”

But does this mean that independence would be the ultimate ending to the Scottish story?

In my opinion, the answer to this question is no; not a no to independence, but a no to independence as the happy identity ending.

There are still many Scots, around 18 per cent according to the 2011 census, who in some way feel British. I am one of those people. Born in Salisbury, England, I moved north to Scotland in 1992, aged one, and have spent most of my life living outside Edinburgh. My father is Scottish, my mother is English, and I have a Scottish accent with an occasional English inflection. I refer to myself as Scottish, but also feel English, and when I’m abroad, which is most of the time, I’m a Brit. In a way, I suppose, this makes me as British as it is possible to be. So if Scotland were to become independent, would my Britishness just die out? If it does, it won’t go the moment independence is achieved.

Then, and arguably more importantly, there’s the reality of independent governance. “Independence is not the end of the story as far as I’m concerned. We have to decide how we want an independent Scotland to be and then we have to govern it,” says Robertson. For now, the SNP government finds itself in an ironically ideal situation. Locked in a negative partnership, it can appear to fight for its people and, if it fails, still have a ruling power to blame. It has yet to decide how it wants Scotland to exist in the world outside of the union.

Leaving the Scottish Storytelling Centre for the final time, a stack of Old Town tales in my hand, I come across a piece of graffiti on the base of Adam Smith’s statue. In scratchy yellow writing it reads, “The Scots blew it!”

Scotland is a country in search of an ending. But, if the storytelling festival has anything to teach us, it is that some stories must be constantly reinvented and refined. If independence comes, Scotland’s narrative will not end: the country will not become more Scottish than it is now, nor will its identity fossilize. The story will continue and the nature of Scottishness will change. For now, Scotland is, like the stories that continue to make it, a work-in-progress.