On the eve of Lisbon’s annual sardine-and-beer bacchanal St. Anthony’s Day, Cara Parks looks at the uncertain future of a celebrated fish.

Thanks in large part to cheap drinks and relatively lax drug laws, Lisbon doesn’t want for a late-night party scene. However, there’s a difference between a city that parties and a city’s party. To experience the latter, you could do worse than being in Lisbon tonight, June 12, for the eve of St. Anthony’s Day.

St. Anthony was born in Lisbon, the child of local nobles. He went on to become a Franciscan friar and legend says that after a particularly frustrating day of preaching to heretics, he went to a river and began preaching to the fish. The fish gathered around to hear him, raising their heads above the water until he finished. It is a fitting story for the city’s patron saint, who today presides over an all-night fête that takes place in a smoky haze produced by thousands of grilled sardines.

For hours, impromptu bars, private residences, restaurants, and the entrepreneurially minded take to the streets with charcoal grills to crank out incredible numbers of the small fish, grilled whole and seasoned simply with lemon, firm and smoky from the fires. They are served on plates with potatoes or stuck between the halves of rolls for eaters intent on moving from one block party to the next. Unlike their canned cousins, the grilled sardines’ char brings out the fish’s salty tang, while lemon brightens the combination into a summery, briny bite.

It’s all washed down with plenty of beer and sangria, which can be purchased from long tables of vendors or from residents distributing plastic cups of the stuff from their street-facing windows. Watch the huge parade, full of brightly costumed participants, head down Lisbon’s grand Avenida da Liberdade, then to the Alfama neighborhood. Ropes of lights are draped over the narrow streets along with brightly colored bunting, and DJs take up residence on second floor balconies to keep pulsing music ringing through the streets until dawn. (Just don’t plan on getting the irritatingly addictive strains of “Ai, Se Eu Te Pego!” out of your head anytime this millennium.)

The entire event makes for something of a launch party for the resurgent sardine, which is becoming more and more esteemed on both sides of the Atlantic, even as questions about its long-term sustainability grow. Sardines generally make up about 40 percent of Portugal’s fresh fish production each year, and have long been a staple in the nation’s cuisine. Traditionally, they were highlighted during the festival, along with less-popular cuts of pork, due to their association with poverty (St. Anthony was a good Franciscan, after all).

However, today, the sardine is undergoing its own conversion of expendable foods into those given pride of plate. For years, sardines have battled a reputation as relegated only to those who couldn’t afford better—a perception not helped by their ubiquitous presence as a canned good outside of Portugal. Over the last few years, however, sardines have developed something of a food-world following. In 2008, a father-and-son team in Lisbon started the Jose Gourmet line of tinned seafood, hand-packed and sporting labels designed by leading Portuguese illustrators. These tins were featured prominently at Tincan, a 2014 pop-up restaurant in London’s tony SoHo district that served only canned seafood.

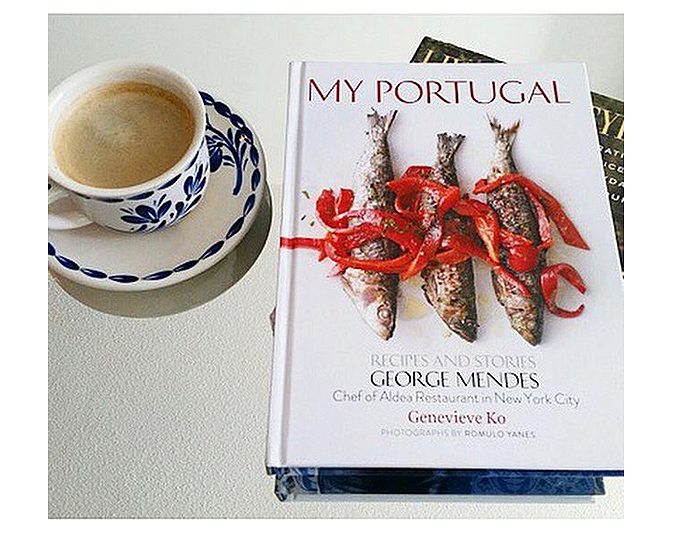

On the other side of the pond, George Mendes—executive chef of the Michelin-starred Aldea restaurant in Manhattan and author of the cookbook My Portugal, which features three glistening sardines on its cover—puts fresh sardines imported from Portugal on his menu whenever he can. Mendes grew up in Connecticut, the child of Portuguese immigrants, and can still remember eating sardines grilled on St. Anthony’s Day during the expat festivals of his childhood. These days, fresh sardines are far less of a rarity in the U.S.

“I’m not going to say they’re just falling out of baskets,” he says, “but it’s been a consistent catch for the fishermen there for the import/export market.”

Mendes says that fresh, grilled sardines have helped change perceptions of the fish as a canned, low-quality product. Of course, getting American diners to embrace a small, bony fish was another challenge. “Once people understand how to clean and lift the filet off the bone and dive into the deliciousness that it is, it’s pretty straightforward. We get the occasional customer who wants us to chop the heads off before we serve them, which we oblige, but in general, people are embracing the whole sardine.”

The U.S. still has a long way to go to match Portugal’s sardine fervor, though. According to the Portuguese newspaper Público, Portugal consumes the equivalent of 13 sardines per second during the month of June, when a series of saint festivals take place. Should you find yourself at any of these festivals, this number seems very, very real. But this sardine boom is taking place at a time when Portugal has seen its sardine harvests drop dramatically. As the paper notes, in 2014, the sardine fishery had its worst showing in 75 years. That year, the fishery lost its certification from the Marine Stewardship Council, which certifies sustainable seafood around the world. (The council had previously decertified the fishery in 2012; it remains suspended for the time being.)

These growing concerns echo the U.S. sardine fishery’s past. A century ago, the Pacific sardine was pressed into service as a protein-packed, portable food for soldiers headed to the battlefield. (Sardines have quite the martial history. Canned sardines were developed after Napoleon Bonaparte—who famously said that “an army marches on its stomach”—announced a reward for anyone who could create a cheap, filling, preserved food for his troops.) By the 1940s, the sardines comprised the largest fishery in the Western Hemisphere. As noted in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report The Rise and Fall of the California Sardine Empire, if the 1936-37 sardine haul from the West Coast (from California to British Columbia) were placed head to tail, it would reach from the earth to the moon and back.

Just a decade later, the fishery collapsed. Despite attempts by the state government to set quotas and curb harvests, which biologists had warned were unsustainable, the boom continued unabated, and by the mid-1950s, hauls were down to one-tenth their historic highs. For decades, the fishery remained in ruins, and after 1968, the legal commercial fishing season was ended. Similar stories have played out at various times in Peru, Japan, and Namibia.

Today, Portugal worries that it could be facing the same battle. Most experts believe that the California fishery collapsed due to a confluence of events, including poor management, climate change, and natural oceanic cycles. A certain amount of overfishing is part of the problem; in 2010, reports Público, Portuguese fishermen caught 64,000 tons of sardines. That same year, intergovernmental watchdog group the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea recommended the catch be halved due to the precarious state of sardine stock, and by 2014, only 16,000 tons were allowed to be brought in.

Climate change is a concern today as well. Sardines are a type of pelagic fish, which live in neither shallow nor very deep water and are hugely affected by water temperature. A study released this year shows that the fish are increasingly moving from their traditional Mediterranean environs to the North Sea and even the Baltic Sea as oceans warm rapidly.

And while overfishing and climate change can’t be underestimated, the natural “boom and bust” cycle of sardine populations is quite real. For example, Pacific sardine stock began to recover in the late 1980s and harvests were slowly reintroduced. However, the remainder of this year’s catch has already been cancelled, as has next year’s, due to declining numbers. Ryan Bigelow, outreach program manager at Seafood Watch, which informs consumers about sustainable seafood options, says that no one is prepared to say exactly what happened to the sardines this year, but natural cycles, which are poorly understood, could be to blame.

All this would seem to indicate that heaping sardines on your plate during this year’s Lisbon festivities should cause at least a pang of guilt. But it’s not that simple. The Pacific sardine remains on the “best choice” list compiled by Seafood Watch, which could augur well for an eventual rebound in the Atlantic, if policymakers make the right decisions. According to Bigelow, the decision to close the Pacific fishery, just like the Portuguese cut in catch numbers, is an example of good management. And in general, the merry-maker at a saint’s festival isn’t what’s driving overfishing in the first place. “The vast majority of sardines are not being consumed by people,” Bigelow says. “It’s not humans directly eating sardines, it’s humans indirectly eating sardines as they’re fed to tuna, for example,” he says, referring to the widespread practice of using the smaller fish to feed larger fish on commercial fish farms.

Should you find yourself in Lisbon this weekend, make your way to the historic Alfama neighborhood. Be sure to have a plastic cup of sangria in your hand at all times. If you’re looking for romance, pick up a pot of freshly sprouted basil, adorned with colorful paper flowers and love notes, which are sold during the party to lovelorn Lisboetas. Dance with the crowd to the Europop blasting down the street. Sardines will be thrown on the coals, perfuming the night with their oily, fishy flesh. Take a moment to ask St. Anthony, who moonlights as the patron saint of fishermen and lost things, to intercede for the shoals of pelagic fish making their way through the Atlantic. Then help yourself. You’ve got a long night ahead of you.

[Top photo by Cara Parks]