Sixty-seven years after the Arab-Israeli War, 3,000 Palestinians remain forgotten and stateless in rural Egypt.

JEZIRET EL FADL, Egypt—

Ghafra dreams of rain. Not the brief bursts of precipitation that mix with the desert dust here a few times a year, but real rain, the kind that makes the worms come out and the watermelons grow, the kind that only falls on one place on God’s Earth: Palestine.

The last time Ghafra saw that kind of rain, she was 13. It was just before the soldiers came, droves of them from the north, west, and south. They left only one path open for Ghafra’s people to escape: west. West to safety, West to Egypt. They planned to only stay a few months, waiting out the end of the fighting.

This month marks 67 years since the war with Israel—and for Ghafra and her people, 67 years of waiting to return home.

Ghafra, now an 80-year-old grandmother, is one of 40 members of the Abu Hussun tribe who fled Beersheba, an oasis in the Negev desert in what is now Israel, in 1948. They journeyed 13 days on camelback across the Rafah border, along the Mediterranean coastline of the Sinai, and southwest to the Nile Delta governorate of Sharqeya. There, they settled on a piece of land they called Jeziret el Fadl—“Island of Favor.” Nearly seven decades later, 3,000 Palestinians remain marooned on the figurative and largely forgotten island.

“Under President Abdel Nasser, we were granted equal status with Egyptians, so nobody set up specific services for us,” says Said el Namudi, the community leader. “But now, they classify us as foreigners and nobody knows about us. International charities don’t know about us.”

Even neighboring Egyptians don’t know about Jeziret el Fadl. The village is invisible from the road, surrounded by a 9-foot wall of mud and brick. Inside the wall is a maze of one-story houses and dirt paths lined by children. Their distinctive light eyes, dulled by malnutrition, watch me with lethargic indifference as I pass by. These children make up 75 percent of the village’s population today, the result of three generations of relentless reproduction aimed at increasing Palestine’s future population, Namudi explains to me.

I first learned of this village’s existence from an Egyptian journalism student. When she told me she had plans to visit the village for a class assignment, I asked if a photographer and I could come along. Four hours and four modes of transportation later, the driver of a motorcycle taxi known as a tuk-tuk pulls up to the one painted structure in the village: the diwan, a community center gifted to them from the Palestinian Authority. There, Namudi greets me, immaculately dressed in a snow-white thawb—a traditional ankle-length Arab dress—and a scarf with a picture of Yasser Arafat pinned to it hanging around his neck. Over coffee, he spends the next hour honestly but diplomatically answering my questions, coating his answers with a veneer of requisite gratitude to the Egyptian state and the Palestinian Authority.

“Egypt has been a gracious host to us,” he says, speaking in slow, elegant Arabic. “All we want from the Egyptian government is for someone who lives in Egypt and was born in Egypt to be treated like an Egyptian. … Today, our poor pay the prices of Egypt’s wealthiest. All we want is for our poor to be treated as the Egyptian poor.” As foreigners, the Palestinians don’t have access to the state subsidies provided to poor Egyptians.

Sixty-year-old Maliha remembers well the days when she could pick up bread, sugar, oil, and rice for mere pennies. Growing up, she never worried about having the right papers—why should she? She was born in Egypt and had never thought to question whether she had the right to be there. But suddenly, about 30 years ago, something changed, she tells me as she swings her scythe at knee-high clovers with gusto disproportionate to her age and frame.

“God knows why, but suddenly, we had to pay for everything,” she tells me. “Everything costs money now.”

Maliha’s husband passed away 17 years ago, leaving her with nine children to care for. She gets by as a modern-day feudal farmer, working a small plot of land for a man from the north who comes by once a season to collect half of whatever she grows.

“I rent the land from him and he takes the final product,” she says, standing up and placing a hand on my shoulder to steady herself. I can feel her pulse pounding through her fingertips as she draws in short, weary breaths. “I have to do everything: plant, water, harvest. But work is good. Work is a gift from God.” She smiles and bends back down again. “Just pray for me that God gives me strength.”

What Maliha doesn’t know is that 37 years ago, after extended discussions in a place called Camp David, her host country signed a treaty that began U.S. military aid to Egypt—and the end of equal status for Palestinians. With the swish of a pen, the state’s allegiances shifted toward the power and wealth of the West and away from the stateless Palestinians, who had become a political nuisance and a drain on the country’s resources.

The situation had already been gradually getting worse throughout the 1970s, but the nail in the coffin came with Camp David and then later that year when a Palestinian assassinated the Egyptian culture minister, Yusuf Sibai, according to Oroub el Abed, a post-doctoral research fellow at the British Institute of Amman. “They started changing laws. During the days of Abdel Nasser, the laws used to say things like, ‘Education is to be free for all citizens, including Palestinians,’ ” Abed says. “But after the killing of [the minister], the words changed to ‘except for Palestinians.’”

As these laws began to be implemented in the ’80s under President Hosni Mubarak, people like Maliha gradually lost access to food subsidies, free education, and free health care—and they were then required to obtain and maintain legal residency as foreigners. Failure to do so could mean fines or even jail time, Abed says.

“They live in prison, literally,” Abed says. “Often, the state turns a blind eye because they know they cannot run after everyone. But when they do catch them without the right permits, what do they do? Deport them where? Nowhere. They cannot deport them. They simply put them in prison.”

Palestinians in Egypt now find themselves at the epicenter of a perfect political storm. Egypt classifies them as foreigners, but shies away from calling them refugees and placing them under the mandate of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, the branch of the U.N. tasked with assisting and relocating asylum-seekers.

“Even though they technically are under UNHCR, the Egyptian government keeps intervening in the Palestinian case,” says former UNHCR Statelessness Fellow Paavo Savolainen. “UNHCR Egypt is under Egyptian law and if a Palestinian were to show up with a UNHCR document, UNHCR would be in big trouble. Usually the argument is that they’re trying to preserve the nationalized entity of Palestinians. So to a certain degree, the Egyptian government agrees that Palestinians are refugees from their own country but they don’t want Palestinians to fall under the mandate of UNHCR. So they created their own national refugee program.”

UNCHR in turn does not classify Palestinians as stateless because to do so would be to tacitly acknowledge that the state of Palestine does not exist. Politics and principles aside however, the hard fact is that Beersheba is now under the ownership and governance of a state called Israel, a state that acknowledges no Palestinian right of return. According to the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ interpretation of international conventions, they are under no obligation to help Palestinians in exile return to their land or find a new home in the West Bank, nor do they have any intention of doing so.

“Once again it comes down to international politics and the very vague status of the Palestinian state, which in practice, doesn’t exist, but to certain theoretical amounts, it does,” Savolainen says. “Last year, UNHCR started a 10-year campaign to eradicate statelessness, but Palestinians, who are actually the biggest stateless population in the world are excluded from the scope of this campaign.”

What’s more, the U.N. Relief and Works Agency—the U.N. branch specifically tasked with serving Palestinians—is not allowed to operate in Egypt. “And that’s why Palestinians are in big trouble,” Savolainen says. To the Egyptian government, Palestinians are foreigners. To UNHCR, they are a political minefield best left alone. And to UNRWA, they just fall on the wrong side of a border.

As a result, for Palestinians in Egypt the only hope for documentation and legal recognition lies with the Egyptian government. The state issues them travel documents (recognized by only Sudan and Saudi Arabia), but it is up to them to keep them stamped with the proper residency permits, issued by the Egyptian office for Palestinian affairs in the mogamaa—the country’s stronghold of bureaucracy in central Cairo. To obtain this vital stamp once they turn 18, Palestinians must either prove that they are studying or working in Egypt, or that they are married to an Egyptian.

“Five percent of our students have gone on to university,” Namudi says, “but they have to pay 10 times what Egyptians pay and they have to pay in foreign currency so it is very difficult.”

Working is also not a likely option; under Egyptian law, businesses are only allowed to open up 10 percent of their jobs to foreigners. As a result, these jobs typically go to highly skilled foreign hires—not uneducated Palestinians. This leaves young Palestinians with two options: marry an Egyptian or hide. In Jeziret el Fadl, most can get by as day laborers or sharecroppers and live out their days in peace and poverty inside the village walls.

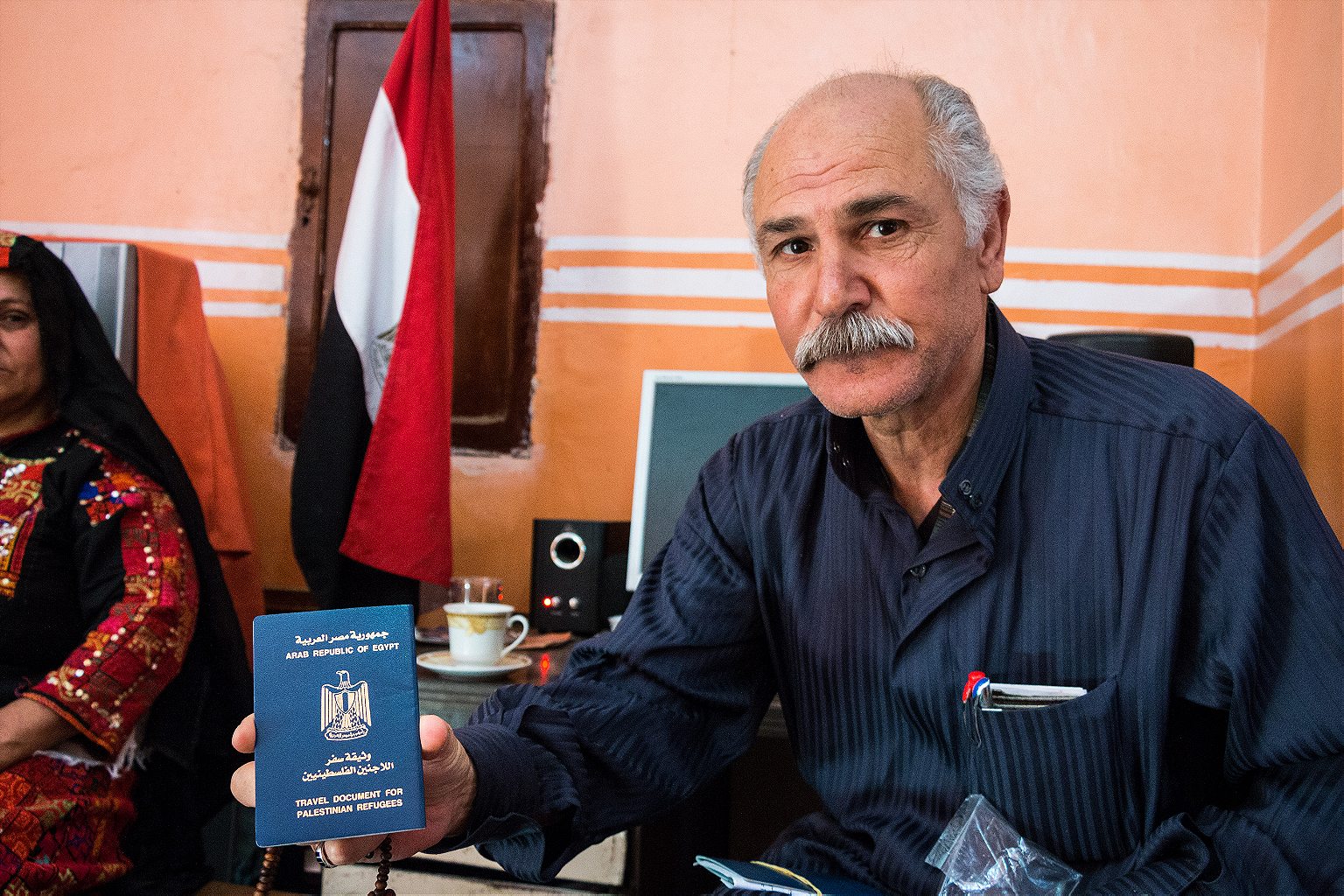

But those with dreams of traveling beyond the village—or beyond Egypt—are best off letting them go. In the old days, 65-year-old Abu Yasser, a handsome man with a thick, white mustache, fathered 17 children with two wives and kept them all fed with frequent work trips to Saudi Arabia, Libya, Jordan, and Iraq.

“But the laws changed in the ’80s and I haven’t been able to travel since,” Yasser says with a shrug. “Who knows why? Political reasons, economic reasons. Only God knows.”

Today, Yasser and his sons feed the family by working as day laborers for nearby farmers, helping them bring in the harvest and sell it at the market. He is grandfather to around 70 children—he lost count a while ago, he tells me, laughing. He keeps his travel document stamped with a special agricultural stamp from Egypt’s ministry of the interior, but he holds onto hope that soon, he won’t need it anymore.

“We’ll return, inshallah, God willing, we’ll return,” he says.

I sit with Ghafra in the cool of her mud-brick house. She looks down at me from one seeing eye, her cracked hands folded daintily in her lap, her long, black hair tucked modestly behind a colorful scarf. Flies buzz around the thatched roof overhead; grandchildren and great-grandchildren hover around her feet.

At 80, Ghafra’s memory is beginning to fade. She no longer knows how many grandchildren she has or who is president of Egypt. But she knows what home is, and she dreams of it still. Home is the smell of camels, soil, and freshly cut watermelon, starry nights, tall grass, and the wild rains from the skies over Beersheba.