The war-torn region has become a major narcotics trafficking route, sparking a new Indian drug epidemic.

URI, Kashmir—

A hand-painted truck carrying a load of Pakistani almonds pulled over in Uri, a lonely, picturesque mountain town in Kashmir, on the afternoon of Jan. 17, 2014. Customs agents had searched the driver’s multicolored vehicle at least 30 times over the previous few years without any trouble. Plus the agents liked the driver. On multiple occasions they had shared a sweet, lightly spiced local tea called kahwa with the man, and they knew about his kids, his wife, and his neighbors on the other side of the line of control in Pakistani-controlled Kashmir.

Border control is a lonely line of work, especially in an isolated region where it often feels like there are more guns lying around than people to carry them, and the agents considered the driver something like a friend. So when he begged the customs agents to speed up their search because he was running behind on his route, they wanted to accommodate him. And they might have even acquiesced politely, were it not for the suspicious eye of Kameshwar Puri of the Jammu and Kashmir State Police.

“The man looked nervous to me,” Puri, 30, recalls of the driver. Puri was about to make the biggest heroin bust in Kashmir’s history.

Where militants and the threat of conflict with neighboring Pakistan were once the primary concerns of border agents like Puri, today heroin pouring out of Afghanistan has created an entirely new menace. Border stations like the one in Uri and others across India’s border with Pakistan in Kashmir and Punjab have become the last line of defense against the growing epidemic of heroin addiction in the country, one that threatens to change the culture of that region for decades to come.

Puri had only held his post at Uri for a few weeks at that point, supervising a team of officers who provided protection to the customs agents. That afternoon it was cold, and the agents folded their arms to their chests to keep warm as they watched Puri stick a long metal rod inside one randomly chosen sack of almonds.

As he poked at the bag, the officers noticed the rod reverberate against something. Puri opened the sack. Underneath a small sea of almonds, he found a tightly wrapped brick of something that looked an awful lot like heroin, pinned with half of a single pink Afghani, an almost insignificant note of currency worth approximately $0.02. More of Puri’s team descended on the scene. The driver dropped his head against the outside of his cab.

“We found 148 sacks of almonds, and 114 of them contained a one-kilogram brick of acetyl morphine, a kind of heroin, embedded in the center,” Puri says. “The drugs were completely pure, so after it reached suppliers in India, 114 packs could have easily been stretched to 500 kilograms or more and then shipped to America and all over the world. It was quite a find.”

Jammu and Kashmir state police gradually learned that each Afghani note had a serial number on both ends: The bills were cut in half and pinned to the packs in order to establish a sort of tracking system, according to Puri. The other half of every Afghani had been couriered into places throughout India, so that recipients of the severed bills could then match the serial numbers with the halves attached to their allotted pack of heroin in the truck.

“Consider that that driver made friends with Border Security Forces across several years in order to gain their trust,” Puri says of the bust, shaking his head. “We’re talking about a sophisticated, well-planned system worth billions of American dollars.”

Eighteen miles from the line of control between the Indian and Pakistani-controlled portions of the contested region, Uri, a lush, mountainous no man’s land of toothy, imposing terrain, is a place few outsiders experience. The region is endlessly captivating, both for its natural beauty and its ongoing air of strife. Large contingents of police and military personnel buffer the divided nations.

The conflict in Kashmir dates back to the Partition of India in 1947 and the formation of Pakistan as a sovereign nation. Since then three wars have erupted between India and Pakistan over the predominantly Muslim region, and violent conflicts between militants seeking independence and the Indian army have been a common occurrence. A legacy of human rights abuses perpetrated by the Indian army and local police during the 1990s and early 2000s continues to haunt the area, leaving many Kashmiris distrustful of authority figures, and making cooperation between press and local officials a difficult balance to achieve.

Photographer Sami Siva and I received permission from A.G. Mir, the head of Jammu and Kashmir State Police, to visit the line of control in December 2014. It was Mir who told us the history of the bust. Uri is a town that embodies the Kashmir Valley in a nutshell: singular in its complex intersection of rising green hills and falling valleys that ripple with tiny creeks; micromanaged by police and military across almost every winding road; and overshadowed by a general sense of oppression and grief.

When we visited, young men played cricket on hilltop fields overlooking the white caps of the Inner Himalayas as armed jeeps rolled past them in single file. Everything in Uri felt like an idyllic fantasy and a militaristic nightmare wedged into the same jaw-dropping dream.

While political violence between militants and police in Uri has erupted on and off for decades, high-stakes international drug trafficking, it would seem, is a new kind of menace, given that trade between India and Pakistan was only initiated across the line of control in 2008. In the roughly six and a half years since then, drug busts have become a semi-regular occurrence, enough that they threaten to shut down trade across that part of the border altogether.

The most common drug crossing the line of control is Afghan-produced heroin and similar opiate-based drugs, whose production has flourished since America’s 2001 invasion of that country. And while the main point of entry for opiate-based drugs to reach India remains Punjab, where in some cases bags of heroin are simply tossed over the border fence like tennis balls, according to police, Kashmir is swelling in significance as a battle point against international heroin trafficking, particularly for larger shipments like the one discovered by Officer Puri in January 2014.

Once over the border, heroin smuggled into India from Afghanistan and Pakistan has an uncertain journey ahead. Some of it, as Puri alleges, is likely shipped out of the country and dispersed throughout the world. Afghanistan produces most of the world’s heroin by a significant margin, and in order to make its way to the distant shores of Europe and North America, logic dictates that it has to leave port from somewhere. Some of it likely flows back to fund terrorist activities, as Puri also alleges, but the degree to which this happens remains uncertain. One more certain effect of the trade is the degree to which India’s people are using the drug.

While drug statistics in India are untrustworthy, Punjab, the neighboring state to Jammu and Kashmir, is plagued with a major heroin epidemic that some doctors and advocates with whom we spoke say could set back the agriculture-dependent state financially for generations to come. Visit any farming town near the Punjabi border of Pakistan, like Ajnala, an otherwise serene district of canary-yellow flowers and sprawling rice farms, and you will not have to look hard to find people shooting heroin. There, locals visit what anti-drug activists call “hot spots,” typically empty areas of greenery along dirt roads, to inject the drug. Discarded heroin needles can be found in these unassuming places by the hundreds, streaked with blood and often snapped in half. Kashmir itself has a less significant problem with heroin usage, but experts with whom we spoke insist that it is on the rise and more available than ever before.

Umesh Sharma, 58, is an addiction counselor based in New Delhi. I first met him in July 2014 at the International AIDS Conference in Melbourne, Australia, where he told me about the depth of the problem caused by flow of heroin over the border. Sharma has experienced North India’s drug epidemic more viscerally than most specialists: He battled heroin addiction from age 15, finally recovering in 1989 through the help of the same kind of treatment and counseling he provides to

others today.

Sharma says that the heroin channeling across the Pakistan border on India’s northern side—like the shipment found in the almond truck—is leaving a trail of addiction that isn’t likely to be eliminated anytime soon. “The drugs coming in from places like Kashmir and Punjab come right here to Delhi and all over the north of India,” Sharma says. “Everything originates from Afghanistan, but by the time anyone sees it, it’s in tiny amounts—just users selling it to other users. It makes the business difficult to trace.”

Sharma also suggests that law enforcement and government complicity plays a role in the flourishing cross-border trade. “If people just did their jobs without succumbing to corruption,” he says, “the heroin problem in North India would be a lot less than it has become. They don’t think of the plight of the users.” Calls on my part to state governments on this subject were not returned, and Mir, the head of the Jammu and Kashmir police, fiercely denies the possibility that any of his officers could be involved in drug trafficking.

One user, who prefers to be referred to only by his initials, H.C., works in a bakery owned by his parents in Ajnala, Punjab, that makes a locally popular semi-sweet biscuit typically eaten by locals during teatime. He is 21 now and has been shooting imported Afghan heroin since two years ago, when he says that an influx of the drug began taking over his neighborhood. He claims that heroin “just showed up” one day in his hometown, polluting his high school, where almost everyone he knew used it. “Ninety-five out of 100,” he says.

H.C. claims to know users who have died from taking the drug, some by overdose and others from diseases like AIDS and hepatitis. He says that he initially tried it because he has a nervous demeanor, and friends said it would help him relax and sleep better. H.C. says that he has never seen large packs like the ones described by Officer Puri and that most of the dealers he knows are just other users of the drug.

“I have no idea how the heroin gets here,” H.C. says. “We users only see it when it’s really small. It just shows up one day.”

When it’s really small, as H.C. says, it looks like it did in his hand on a cool December afternoon when we followed him to a local creek in Ajnala, Punjab. There, he opened his palm to reveal a small red package about the size of a gumdrop with a little ball inside made of yellowish powder. H.C. took the ball and put it inside of a clean syringe and filled it with dirty water from the filmy creek, not more than 10 yards away from where a buffalo was taking a bath. He injected the drug, shook his head in a state of intoxication, and offered us a ride on his motorcycle, which we politely declined. Then he lit a Navy Cut–brand cigarette and reflected on the plague of addiction that surrounds his neighborhood. “For the sake of the family, drugs like this should always remain banned,” H.C. said, his eyes narrowing from the high. “People who sell it I think should be punished.”

To date, the recipients of the other halves of those severed Afghani notes have never been punished. This is due largely to the complexities of police work between hostile international borders and the anonymity of many courier exchanges in the region. Likewise the faceless people involved on the other side of the border—in Pakistan and in Afghanistan—also remain wholly invisible.

The driver of the truck, a Pakistani national who cannot be named in this article for legal reasons, is the only person who’s been arrested. Puri speculates that the driver was just a small-time player working for extra cash, and never even knew the magnitude of what he was transporting until it was too late. In his office, Puri serves us hot kahwa and biscuits and shows us photographs of the Afghanis taped to the heroin packs with a mixture of pride and amazement, as if he still can’t quite process the sophistication of the system he uncovered. He also shows us a photo of the driver, standing in front of his hand-painted truck, his face sagging off the bone in despair.

“You could see on his face that he was not having a good day,” he says, wryly.

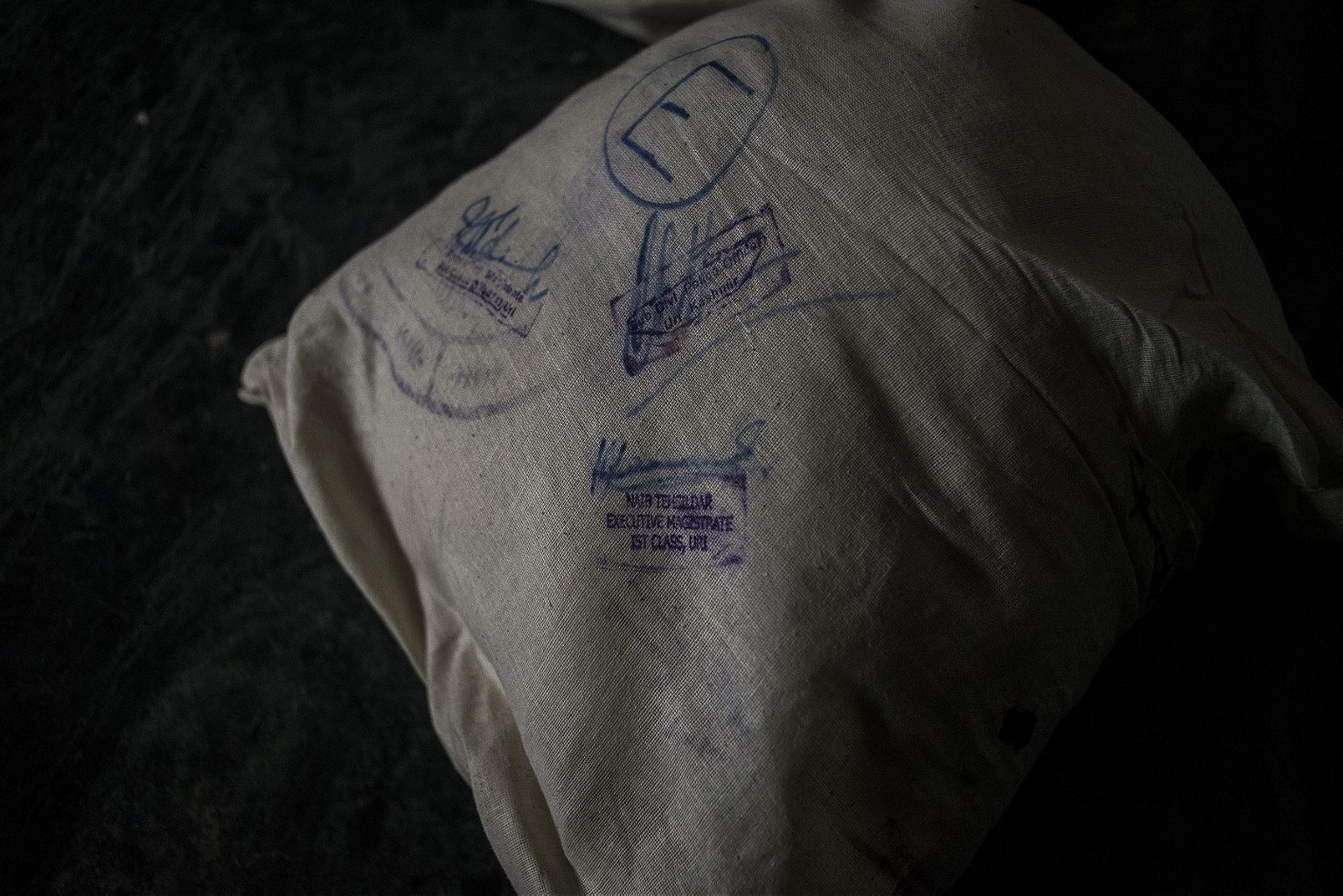

Puri, along with his team, gave us a curated tour of the evidence, in which we saw the heroin that was seized on that day sealed tightly in canvas bags, nearly a year after the arrest took place. The drugs are awaiting an order from a judge, who will request that they are burned—standard protocol for heroin seizures in India, according to Puri. He also showed us the truck, now rotting lifelessly inside of a police compound surrounded by a sprawling view of mountaintops from every angle.

“There it is,” he says with shrug.

To reach the customs bay inside the line of control where the truck was first pulled over, we drive across five or so check points where members of the Indian army, secured with AK-47s, check our paperwork and sniff through the interior of our vehicle, a tourist car, manned by a driver hired for the day out of Srinagar, the summer capital of Kashmir.

The only civilians in this military-controlled area of Uri other than us are people who are indigenous to the region and therefore permitted to stay. They live down in the valleys, mostly—Indian by nationality, but only by less than a mile in terms of geography. We only see glimpses of their children, most of them preteen boys. They are pushing what looks like an old, abandoned refrigerator up the side of a massive green hill and whacking small stones with a plastic cricket bat.

Over at the customs bay, a line of trucks not dissimilar to the almond truck sit docked for unknown reasons in a line, painted with tiny images of birds and tagged neatly with crisp Urdu writing. Around the bay is nothing but rock and forest and the peaceful sound of the cold wind whipping off of the hills.

“You try to get everyone,” Puri says of combating the drug trade. “But there are always new people trying to think of new ways to get through here.”

Travel for this story was funded by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.