After a decade of working in Myanmar, a photographer finds hope in an organization that empowers young women.

In 2010, as Aung San Suu Kyi was released from seven years under house arrest, an organization designed to empower young girls in Myanmar was quietly seeing the light of day. Its grassroots approach was innovative: it combined education and a way of meeting that resembled group therapy. As Myanmar was rolling out its democratization reforms, Girl Determined expanded. By 2012, Suu Kyi was sworn into Parliament and the program counted hundreds of participants. The same year, photographer Andrew Stanbridge was entering the country on a journalist visa for the first time. After meeting Girl Determined’s first participants as they finished their two-year programs, he embarked on a long-term project to document the organization. “It’s a group that is very close to my heart because I photograph a lot of terrible things,” he says. “So it’s just one of the more positive things in my life.” After three years of working on the project, Stanbridge is flying to Myanmar this week to prepare for his first exhibition there. He spoke to R&K from California.

Roads & Kingdoms: Tell us about the exhibition you are preparing.

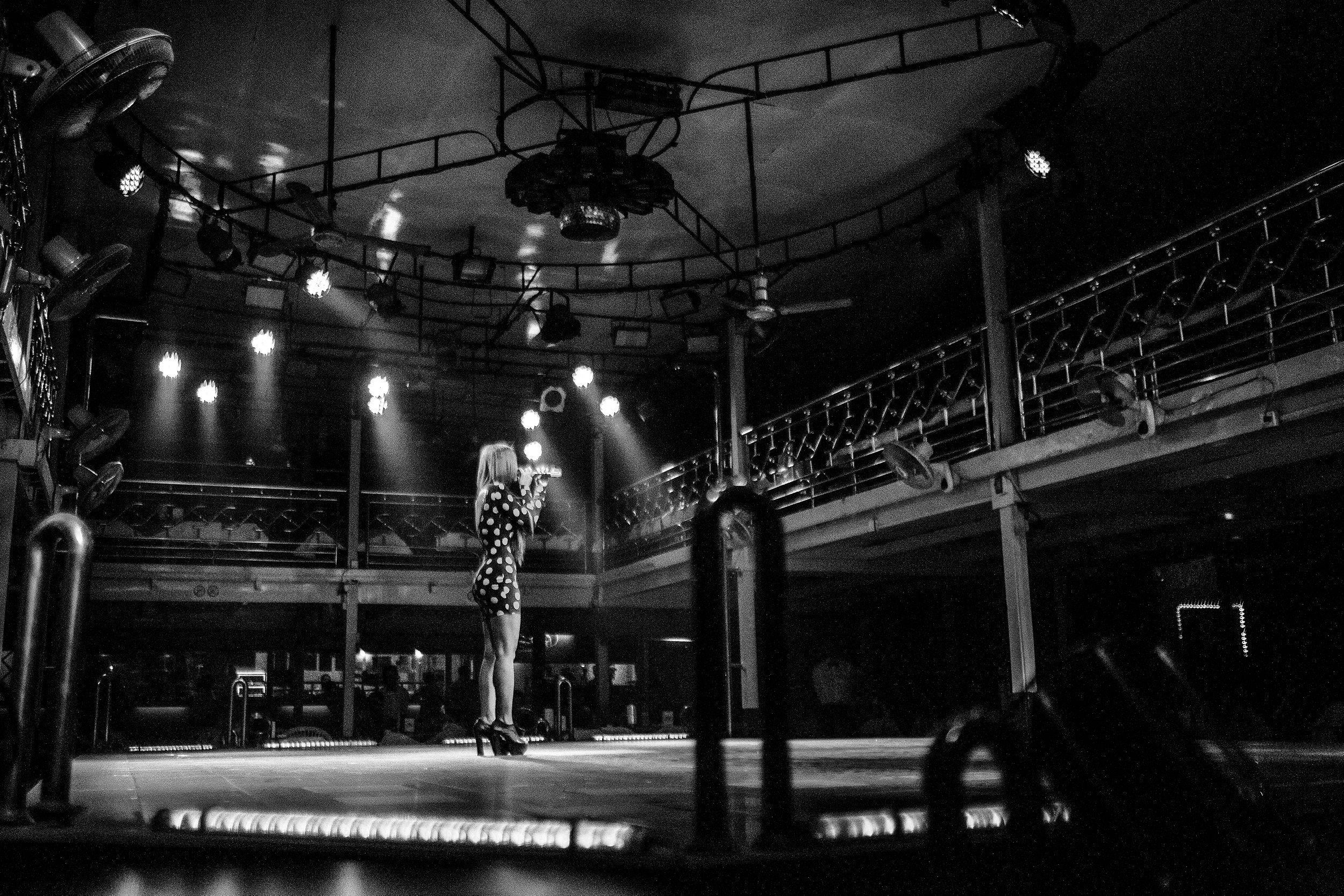

Andrew Stanbridge: They are photographs that I have been taking for the past three years with Girl Determined. It’s their five-year anniversary and they had to operate under the radar for a while, so now with the opening up of the country, this is sort of like their coming out party. The exhibition will be in a beautiful, old colonial building and showcase about 40 photographs of the girls, the groups they work in and their daily life. Many of them will be present.

R&K: When did you first hear about Girl Determined and why did you decide to document their work?

Stanbridge: I was doing a Fulbright in Thailand in 2001 when I met a woman called Brooke Zobrist, who was getting her master’s degree at Chang Mai University in refugee studies. She was doing a lot of work with Burmese refugees on the border of Thailand and we became friends pretty quickly. She then started to shift her focus of study to the stuff that was happening inside Myanmar, and moved there about seven years ago. That’s when she realized that some of the most direct problems had to do with women, so she built this program and devised a curriculum that could work to empower girls. We stayed in touch and I would always visit her, and three years ago I offered to do some photographing and video so she would have content that she could use for the organization. She’s just somebody who has been working there for so long and she has incredible resources, contacts, and understanding of the country. And she was quickly starting to impact these girls’ lives.

R&K: You had been taking photographs in Myanmar for a while already.

Stanbridge: I went for the first time 15 years ago, in 2000. It was my second trip to Asia, and I didn’t know too much about the country. I mean, nobody did. I remember my dad saying, “please don’t go, it’s such a dangerous place, there’s a terrible military government and it’s not safe.” And like so many places that people tell you are not safe, it’s really the people who are living there who aren’t safe. As a person traveling in, it was just an incredible experience to learn about the conditions and how truly oppressive and repressive the military regime was and continues to be. I’ve been going back almost every year since then, at least once if not more, and covering different stories throughout the country.

R&K: What kind of stories were you doing out of Myanmar at that point?

Stanbridge: All sorts of things. Religious tensions, illegal wildlife trade, sex trade, I was doing a lot of refugee stories as well in Thailand, that’s really how I got interested in Myanmar. When I met all these workers who were illegal immigrants, working in slave-like conditions. It made me want to go and see what the country was like and how bad it was that these people felt like they had to leave their homes, their families, and come work in these terrible situations. I have worked on the Rohingya story for the past two and a half years now, also on the economic disparity between the people and the members of the junta, and the way that they use the environment to make tons of money. Coal mining, the jade industry, the oil industry, a lot of the Chinese influence that’s coming in and sort of just pulling these resources out while the commanders sell the country down the river so to speak.

R&K: How did your coverage of Girl Determined fit into all of this? And when did you decide to do this as a longterm project?

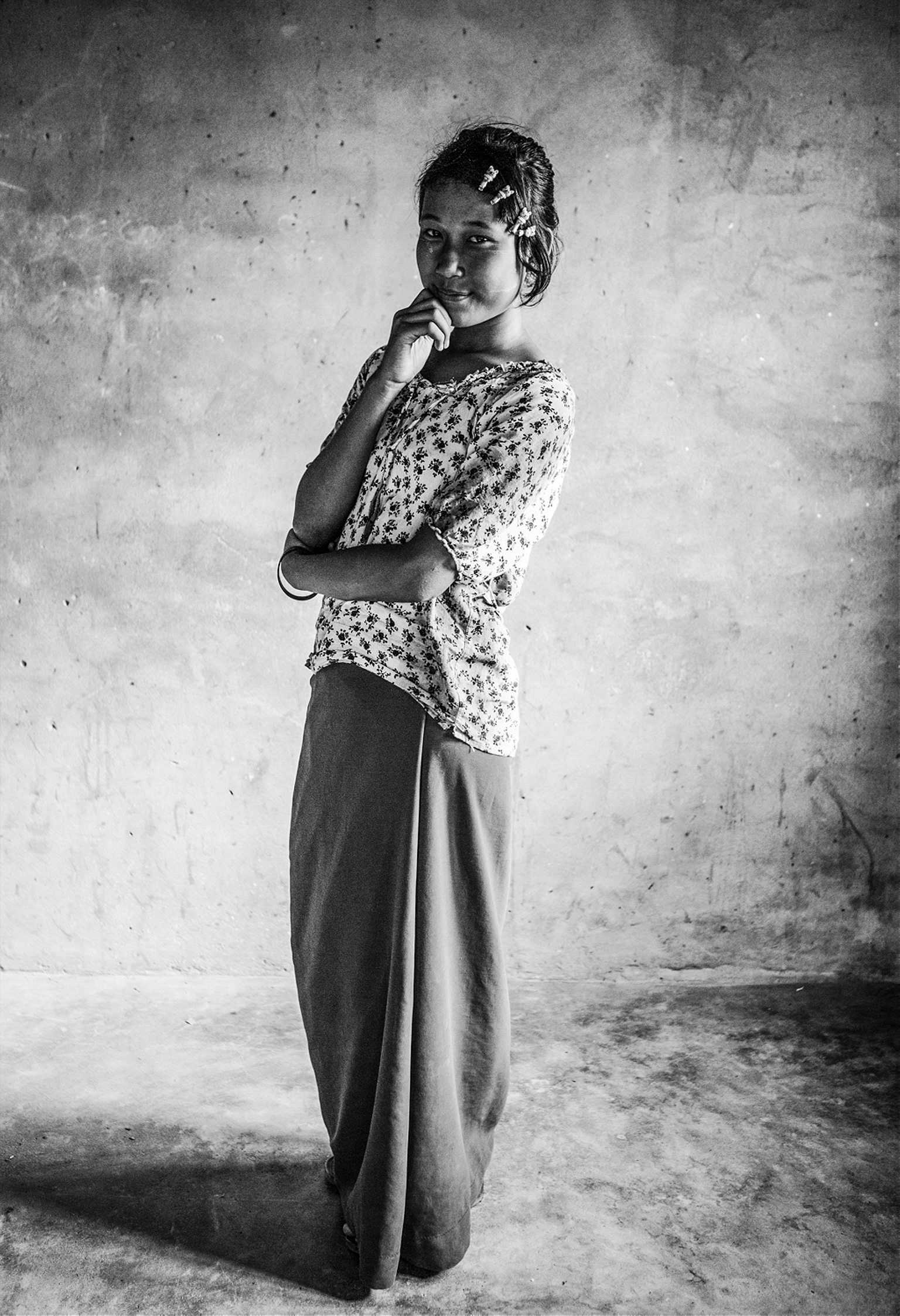

Stanbridge: I go and photograph a lot of terrible things and I see a lot of groups trying to help, but this is one organization that just amazed me. The direct repercussions that it has had in two years and just how much the girls have changed. All of a sudden, they go from being these scared, closed-off people to realizing a sense of self and developing hopes and dreams. In the first couple of days of working with them, we interviewed the younger girls and heard these stories, which were just heartbreaking, like so many stories that I heard before all over the world. Alcoholic parents, beatings, being forced into factory work, being forced to quit school, having to take care of younger children, all of these things. Then, actually going out and seeing the project and talking to the girls who had gone through the two-year program, and just seeing the dramatic shift was just really inspiring to me. So I said, “let’s keep doing this and let’s get stories over the years.”

R&K: How does the program actually work?

Stanbridge: It functions in what they call “circles,” which are groups of around 10 to 15 girls that go through a full curriculum that the founders have developed. Girls start out just getting to know each other, communicating, then they have them dig deeper into their own emotions and start to learn how to share those emotions and that’s a big, transcendent point. Often these feelings have just been suppressed, suppressed, suppressed and a community of people who have been through the same experiences is a comfortable place for these girls to be. So they start to share these things and I think a huge weight comes off their shoulders. Then they think about the resources that can help them affect change, how important education is, and work on goal-development and things like that. At the end, they work on projects together that can benefit the community.

R&K: How do the girls come across the program?

Stanbridge: Brooke and her team are constantly traveling around the country and finding areas where the work is needed the most at the moment. They look for local women to train as leaders. Those leaders then go to the schools or the temples. It’s really interesting because usually the temples are such male-dominated areas, so the head monks get really excited about being able to help these girls. Usually a couple of girls will sign up at the beginning, maybe five or six who show interest, and really quickly the other girls see them meeting and doing these projects and laughing together and all of a sudden more and more start coming in.

When I’m working I just try to get in the mindset of the people whose story I’m telling.

R&K: As a documentary photographer, how did you approach this project? This is very different type of work than you’re used to.

Stanbridge: Absolutely. You know, they don’t have any media liaison or anything like that, so it’s really just me asking them if we can interview some girls, if we can sit down in a house, if we can do this and that. And then I also usually stay in the village or nearby for a few days at a time so I just walk around and watch the daily life of the girls, photographing that kind of thing. So there’s no ask for content or anything like that from them, I just hand over the stuff that I think that they can use to create outreach. I’ve covered a lot of the aftermath of war in various countries and I feel like that’s always a neglected story with the media, but it’s a neglected story in a depressing way. This was a story where the roots are depressing but the outcome is exciting and positive and makes me feel like there’s hope for the world.

R&K: Was it every difficult to work on this story as a man?

Stanbridge: That’s a good question. In the beginning I usually just tread softly and stay in the background a little bit, as I do with any story really. After a couple of days, I develop the dance of ingratiating myself to people and so by the end of it the girls are all running up to me and laughing and giggling and stuff like that. It’s a funny thing though. When I was doing stories about bomb clearing in Laos, one day somebody took a picture of me and the bomb clearing team. I’m a really big guy, and when I saw on the photo that everybody was elbow-height to me, I was just like “wow that’s crazy” because I just identified as one of them and saw myself as one of them. I feel the same way about these girls, and I think if I saw a picture of me with them, I’d be equally surprised. When I’m working I just try to get in the mindset of the people whose story I’m telling. I probably look way weirder than I think I do.

R&K: After three years of working on this project, what do you think the story of this organization says about Myanmar as a whole?

Stanbridge: I think it says something about the world as a whole, actually, in that we need to have a bit of a shift in paradigm thinking about who can affect change. There are so many societies that repress women. That’s half of our population. It makes you realize how much we have put the brakes in terms of development on all sorts of levels. Just seeing in two years the impact that a very simple, very underfunded program can do is amazing. What I hope is that people in other countries can pick up on it, and so we’re not just talking about changing Myanmar but we’re also talking about changing the world. I just think about all those places that I’ve visited, and how amazing it would be if I was walking through the streets of Syria or the streets of Ethiopia and saw the girls out there participating to society, and not hiding behind the shutters.

R&K: You’re very optimistic about this program, and yet not so much about the future of Myanmar.

Stanbridge: That’s absolutely correct. It’s easy to be pessimistic about the grand pictures of things, looking at a country and all of its problems. And it’s also easy to be overwhelmed and think that there is no change. The commanders of the Kachin army are constantly going to be wanting to throw bombs at the commanders of the Burmese army. As a single person, you have very little chance of changing the winds of that. But I used to look at the plight of women in Myanmar in the same way and when I started to gaze in and see the changes that Girl Determined can make, it does give me hope.

R&K: Were some aspects of Myanmar’s democratization reflected in your project?

Stanbridge: It definitely goes hand in hand. The whole country itself has gone through a change in the idea of hope for the future and that affects every facet of a society. I think that talking to these girls and telling them that they can become a politician or something like that, that’s all of a sudden a much more realizable dream. Five, ten years ago Aung San Suu Kyi was a figurehead of resistance rather than somebody who is actually working within the system, which seems like a much more approachable vehicle for that change.

R&K: You’ve mentioned before that this project was extremely redeeming and rewarding. How has it impacted your career as a documentary photographer?

Stanbridge: I don’t do a whole lot of jumping in and out of situations. I work on longer term projects, and so I make alliances with organizations or with individuals that are working with longterm visions and goals. And I try to give back to these communities as much as I can, that’s a very important thing. It doesn’t just make me feel good and help the community, but it tends to also mean that I’m developing relationships with people that will allow me to go further and further into the stories. Respect for me is such a huge thing. If I’m not respecting them, how can they possibly respect me? I want to be somebody who, when I’m walking down the street for the 10th or 100th time, people will wave to and I will wave back.