Will dams in Southeastern Turkey be used as weapons of war?

HAKKARI, Turkey—

As we neared Hakkari province in Turkey’s far southeast, bordering Iraq and Iran, we began to see the helicopters flying overhead. There were military bases scattered among the mountains, resembling medieval castles. At checkpoints we were asked to show our passports or IDs. My friend, who is Turkish, joked: “You see, even the Turkish government thinks this is not Turkey!”

Hakkâri is more than 1,100 miles from Istanbul, a mountainous region populated mostly by ethnic Kurds. It is renowned for its untouched natural beauty, fertile plains, snowcapped peaks, and clear water. It is also the site of ongoing conflict, and many Turkish view it as a hotbed of terrorism. Battles between the government and the guerrilla army of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a militant organization that has been fighting for Kurdish independence since the eighties, are ongoing.

The high mountains and proximity to the foreign borders make it an excellent area for guerrilla tactics, and the local Kurdish population generally supports the PKK. As Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned PKK leader, once said: “Hakkari is where we are the strongest.” Few visitors enter this area, and the strong presence of the Turkish military makes it feel inhospitable.

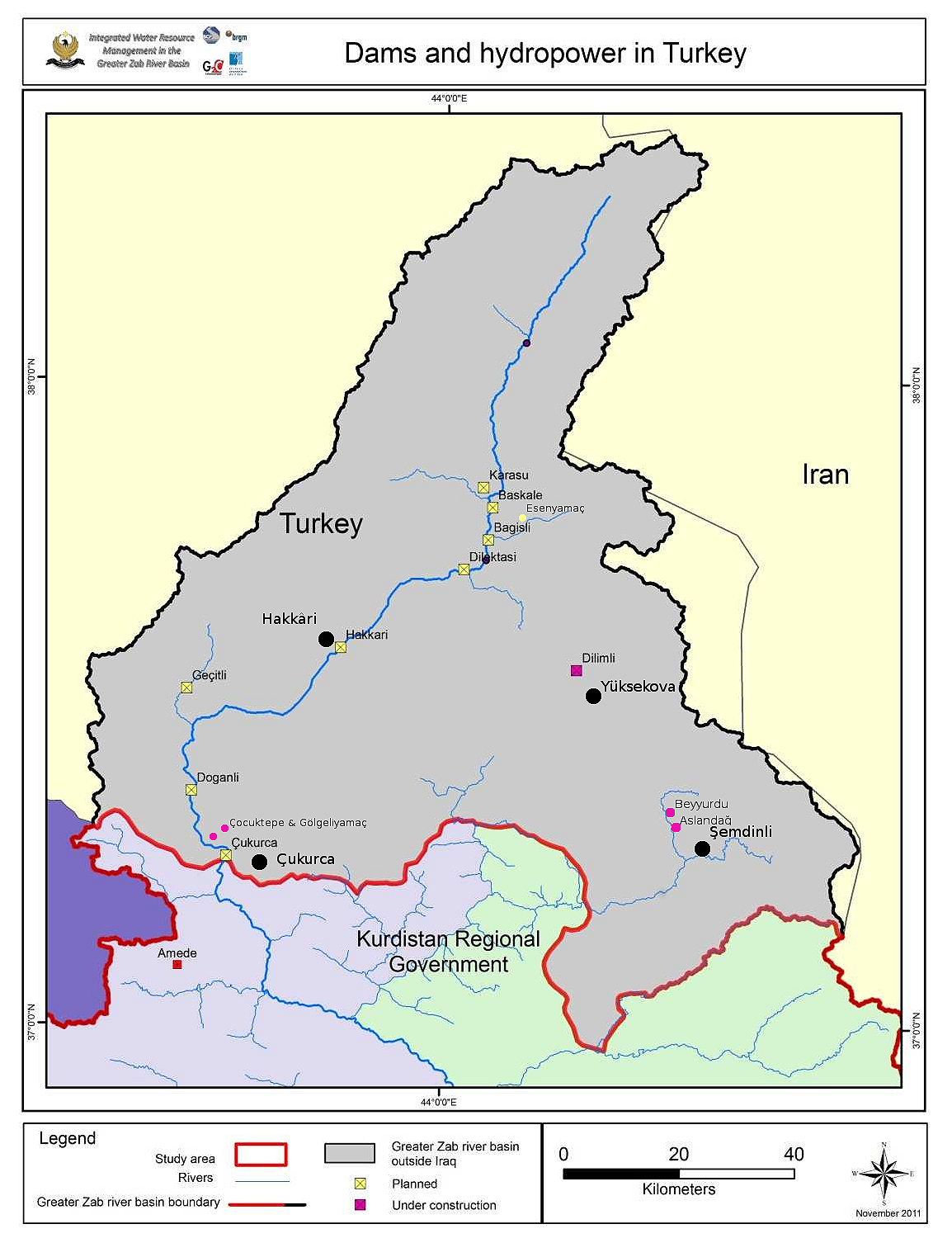

I was there in 2013 and 2015 to investigate a series of state-funded dam projects that locals believe will be used for military purposes. Some academics have reported that the so-called “security dams” are actually part of a broader war strategy by the Turkish government, to counter the PKK. When traveling to Hakkari along the Iraqi border, several half completed dam structures can be seen. The government has claimed that the dams will bring electricity and foster development in the poverty-stricken, mostly rural area, and that they are part of a nationwide plan to use all Turkish water resources by 2023. As Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said in 2011 when he was the country’s prime minister: “No river should run in vain.”

In the Hakkari and Sirnak province over a dozen dams are planned. In Hakkari especially the Greater Zab river is of major importance, a key tributary to the Tigris River. In comparison to mega dams such as the Ilisu or Mosul dam, the dam reservoirs are small and deep due to the steep valley. Four larger dams would be directly on the Greater Zab River and would contribute the major share of the estimated 1100MW power generation. Those projects combined are estimated at over a $1 billion.

The exact environmental impacts remain unclear, however some of the dams are located in Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA) and would flood those. KBAs outline internationally important areas through standardized indicators in order to conserve global diversity.

But the local populations believe the dams will flood the hideouts and routes of the PKK. The rough mountainous terrain will be less accessible for guerrilla activity. Moreover, the villagers living in those areas will be forced to move toward the city, making them easier to control. Others complained that their smuggling activities would be curbed; indeed the towns are filled with smuggled goods ranging from gasoline to tea.

In 2008, during the announcement of the dam projects along the Turkish-Iraqi border in Hakkari and the neighboring Sirnak province, the General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works admitted that the dams are “security dams against the PKK.” For many Kurds it was another reason to oppose those projects. Today, however, the government denies this statement.

In Hakkari I drank plenty of tea with locals and smoked smuggled cigarettes in dusty towns. Wherever I went I heard the slogan, “Long Live Kurdistan, Long Live the PKK.” I visited a dam construction site in Semdinli, a district with stunning greenery also known for PKK activity. In a small village on the mountain slope a local construction worker told me that none of the necessary parts for hydropower generation were installed. According to a local politician with a thick mustache from the opposition Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), the dams are the same as military bases: Simply another way to suppress the people in this rebellious province.

The PKK also sees dams as a direct attack and objects for several reasons. One PKK member in Iraq who has been in the organization for 23 years, told me:

“They want to own the root of civilization. Dams are one of the methods to destroy the Kurdish history and culture. They use it to flood archeology, to divide communities, and to make us leave our mountains. The people get forced to live a modern life and forget their roots. They divided us over the countries when they drew their borders and they want to divide us through those dams as well.”

The PKK has made repeated threats to attack the dams. In 2012, 22 trucks were set on fire supposedly by the PKK and construction workers have been kidnapped several times by the organization.

The dams are state backed-projects in an area of the country where distrust towards the state runs deep. “This is the lawless East,” a local lawyer explained to me. “The laws of [Western Turkey] don’t count here.” In one case, the house of one family was severely damaged in explosions related to dam construction, but no compensation was offered. Nor have local villagers been invited to participate in the decision-making process.

In Hakkari I attempted to speak to several local government representatives. Most of my attempts failed. One of the governors agreed to speak, but as soon as I started enquiring about the dams, the conversation ended. In 2009 two French students were deported for researching the purpose of the planned dams. I tried to comb the public record for information about the dams, but was thwarted in this effort too. Even though Turkey has a law that ensures public access to information, simple facts such as where the dams are being built, when, and how large, was not publicly available.

Eventually after having plenty of tea and friendly conversations at the Hakkari environmental policy department, I was allowed to look at the Environmental Impact Assessment—but only if I agreed not to tell anyone.

Finally I arranged a meeting with a tense local official, who agreed to speak anonymously. Sipping tea, he insisted that the dams would not be used against the PKK, but instead for generating electricity and creating much needed jobs.

But he still believed the dams should not be built. A native of Hakkari himself, he lamented the environmental impact of the dams. “The next generation will curse us,” he said. “Our thousands years old glaciers will melt, and the indigenous nature of Hakkâri will disappear.”