A year after its destruction, Cairo’s Museum of Islamic Art remains a bombed-out shell.

CAIRO, Egypt—

At 6:30 a.m. on an unseasonably warm Friday in late January last year, a parked car filled with high explosives detonated outside Cairo’s famed Museum of Islamic Art. The blast blew out the building’s cathedral-like windows, hurled a streetlight through the thick front doors, and pockmarked the façade with cannonball-sized cracks.

Inside the cavernous, smoke-filled space, the devastation was even more jarring. After boring a deep crater into the road at the foot of the adjacent police headquarters, the shockwaves had torn through the flimsy aluminum shutters and shattered over 250 displays of ceramic art and glasswork.

Museum employees, like many other city residents, were rocked awake by the bombing, the work of Sinai-based jihadis. The staff soon dashed to the scene, where security services had strung up a tight cordon to ward off would-be looters.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), international governments, and private donors were quick to pledge support, and antiquities officials swiftly announced an ambitious plan to repair the damage within a year. But Egypt’s bloated bureaucracy is notoriously fond of endless committees and nowhere has this glacial pace of government administration been more keenly exhibited than in the authorities’ clumsy efforts to reboot the museum. From frequent delays in kick-starting construction, to the events immediately following the attack, the restoration has become mired in confusion, red tape, and allegations of corruption.

The problems began immediately after the blast. Amid the chaos, curators were unable to locate the distinctive Allen key required to lever open the intricate locking mechanisms for the few showcases that withstood the explosion. As water from the sprinkler system seeped into the cracks, desperate workers resolved to smash their way in, but succeeded only in chipping other valuables and mixing new glass among the fragments of 1,000-year-old lanterns and urns.

It was at this point that Egypt’s complicated political dynamic also intruded, according to several independent conservationists who asked to remain nameless. A pair of specialist German conservators arrived to offer their services, but police allegedly denied them entry due to their organization’s association with pro-democracy activism and the revolution of 2011, which many members of the security apparatus resent.

Fortunately for supporters of what many see as the world’s greatest collection of Islamic art, all but 17 of the shattered treasures look to be salvageable. As of December, 160 had been pieced back together.

But Hamdy Abdel Moneim, the head of the restoration department, is still consumed by the loss of various treasures.

“I was tearful when I saw the damage. So much history was destroyed,” he said, while surveying an eighth-century pot hailing from the reign of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, which one of Moneim’s apprentices had been painstakingly patching up for three months.

Almost everything in the museum has since been moved out. Only a pair of bored security guards keeps watch over the dust-caked interior. A few large Mamluk-era floor tiles proved too heavy to shift, and so they’ve remained hitched against the wall. So too a seventh–eighth century Umayyad Quran, which is supposedly one of the earliest recorded examples of the use of vowels and consonants, and which somehow survived the blast unscathed.

“We believe its survival was a miracle,” said Ahmed el-Shoky, the museum’s director. “It was directly in harm’s way.”

But the museum’s still-bare windows and mounds of mangled metalwork and other debris piled in the corners speak of a construction process that has yet to really get off the ground.

American conservation authorities have had an offer to repair the façade accepted by the Egyptians, but without a final green light from the Ministry of Antiquities, which administers the museum, they’ve been unable to do more than erect scaffolding. “They were tortured by the approval process. They were ready to start in April,” said Tamara Teneishvili, a cultural expert at UNESCO’s Egypt field office.

Some ministry officials are relatively open in expressing their frustration with the pace of work. “The Egyptian routine makes things move slowly. I’m trying to change this,” said Shoky, who was appointed in September to shake things up. By way of comparison, the restoration of the Cairo police headquarters, the intended target of the Sinai-based jihadi group that claimed responsibility for the attack, is almost complete. The group claims the museum was collateral damage in its campaign against the state.

Much of this inertia is the result of the severe financial crisis Egypt has grappled with for the past few years. The Ministry of Antiquities is flat broke—operating off a deficit of 3.5 billion Egyptian pounds (about $460 million), and as the only government department required to self-fund, it’s been hit hard by the absence of tourists and corresponding loss of ticket receipts.

Having spent around $10 million turning the institution, which first opened at its current site in 1902, into a world-class facility between 2003 and 2010, the ministry now appears to have let its renewal slip down its list of priorities. “After only three years, it was bombed and destroyed, so it’s difficult for us to take funds so soon,” Shoky said when we met last November.

Authorities did receive a terrific boon a few months after the bombing when the United Arab Emirates—which along with Saudi Arabia and Kuwait has been propping up much of the Egyptian state—announced it would issue a blank check to cover costs.

No concrete figures were bandied around (though UNESCO suggests it will take $25 million to fully restore the museum), but things soon took another turn when the UAE’s cultural center in Cairo supposedly began to query the amount of money antiquities officials were requesting.

“The quotations [from the ministry] are overinflated and the Emiratis are not ignorant in this matter,” said a source familiar with the negotiations who spoke on the condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the situation. The UAE subsequently conducted its own cost assessment and struck a deal with a military-backed contractor to carry out the work instead of going through the ministry, the source added.

On top of everything else, the destruction has triggered a broader discussion about the institution’s design, location, and long-term structural issues. Some Cairo residents fear further terror attacks on nearby security installations, but with the museum abutting a busy traffic-filled thoroughfare, the site appears incapable of supporting a surrounding protective wall.

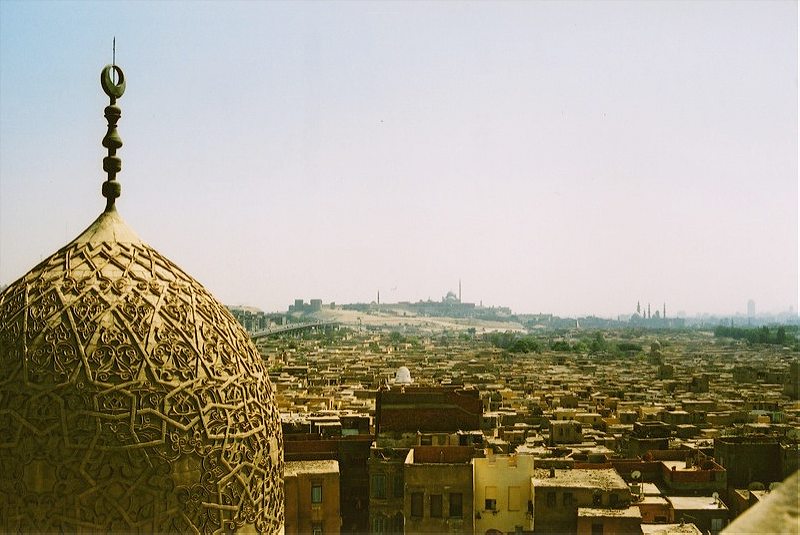

“I think that Cairo and a collection of this grandeur deserve better. It’s not secure, there’s no space between the building and the street, and the pollution is very bad. Perhaps it was a superb location 100 years ago, but it’s not today,” said Omneya Abdel Barr, an architect and conservationist, who’s one of many experts pushing for a move.

With water gushing in from the neighboring Port Said Street, which was once a canal, the basement storerooms already seem unfit for their intended purpose. “There are leaks and breaks so big you could put your arm in them,” said Shahira Mehrez, a former member of the museum’s advisory board, after an inspection last year. “You would not accept to throw your dirty linen in them. There are bits of wood, stone, and Fatimid textiles broken with dust all stacked on top of one another.”

Poor museum storage is not a uniquely Egyptian problem. Even the Louvre has been accused of treating its collection with insufficient care. But the Cairo museum’s structural issues have been compounded by a lack of coordination between the Ministry of Antiquities and the Ministry of Culture, which oversees an annex of the national archives above the museum.

An unwillingness to cooperate—a consequence, some say, of the enduring enmity of culture officials, who had authority over the antiquities department until a few years ago—has meant that the building has two different air-conditioning systems, which have thrust a lot of unnecessary weight on the roof. Museum officials also accuse their counterparts upstairs of placing undue strain on the foundations by adding inappropriately placed extra columns.

“They really just need to sit down together and ask how they’re going to deal with the monuments of Islamic Cairo,” Mehrez said.

The bomb did at least provide the impetus to conduct a full review of the museum’s contents. Only 1,500 of the collection’s roughly 92,000 objects were on display at the time of the bombing, and most haven’t seen the light of day since members of Egypt’s deposed royal family donated the bulk of its treasures in the early 20th century.

In digging through the museum’s tattered paper ledgers, officials found that at least seven pieces of historic decorative metalwork had disappeared over time, while an 800-year-old lantern from the Sultan Hassan mosque, believed to have been stolen more recently, is rumored to have cropped up on sale in London in October.

Conservation experts can only shake their heads in befuddlement.

“I just get the impression that this bureaucracy is strangling all initiatives,” said UNESCO’s Teneishvili. “It’s a marshland.”