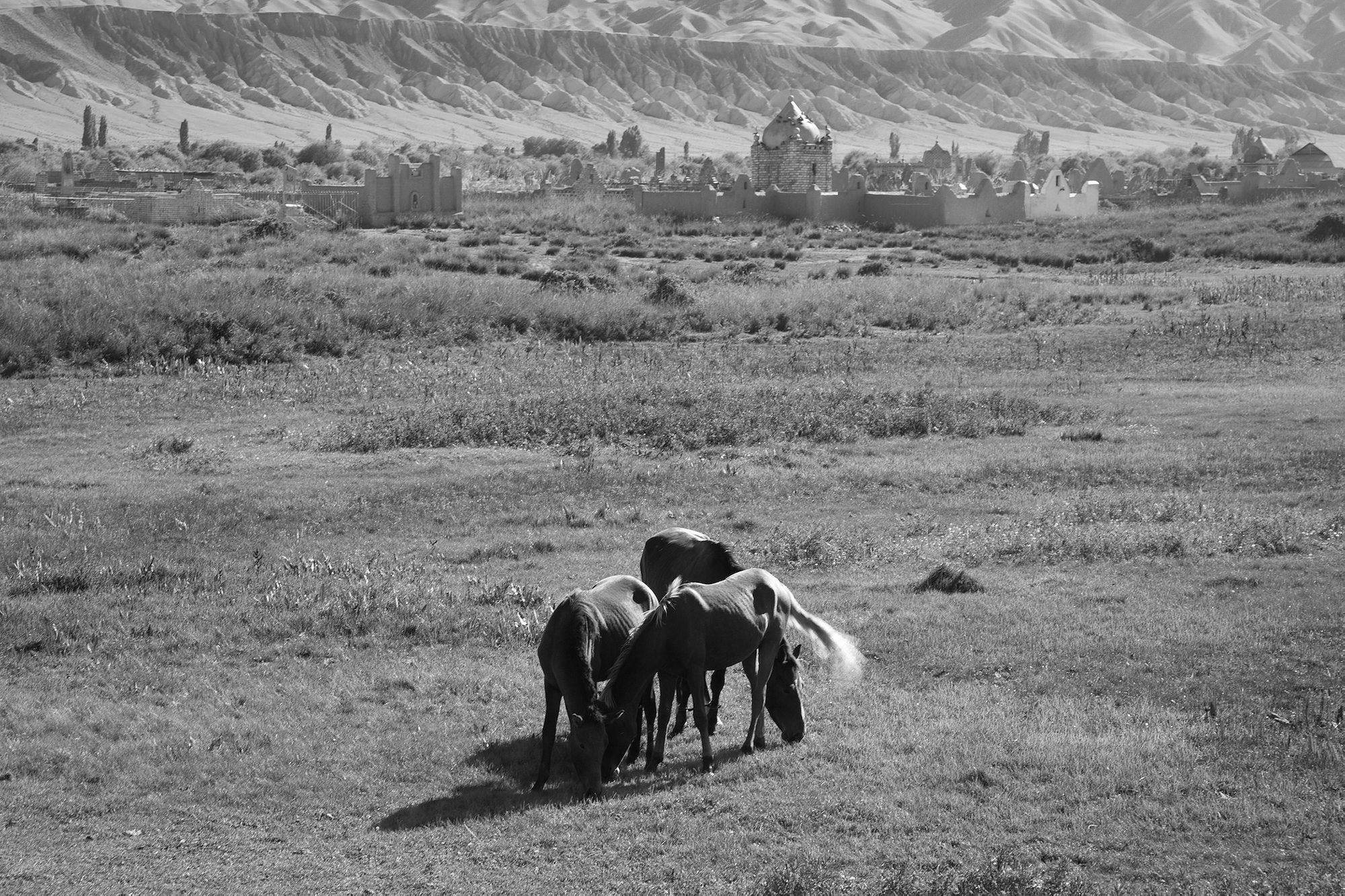

Crawling up mountains or lying in deserted plateaus, Kyrgyzstan’s ancestral cemeteries reflect the country’s complex religious and cultural identities.

The graveyards are scattered throughout Kyrgyzstan’s countryside, flanking mountains and standing sentry on deserted plateaus. Tombs built like giant bird cages and mausoleums topped with delicate stars and crescents appear like mirages against the jagged landscape. It’s a spectacular sight, but few are there to witness it: it is not Kyrgyz tradition to visit cemeteries. In 2006, photographer Margaret Morton became fascinated with the earth-colored structures, which blend Islamic architecture with nomadic and Soviet influences. Over three summers in Kyrgyzstan, she traveled to more and more remote places to uncover their stories. Her book, “Cities of the Dead,” was published in November. We met her at the Cooper Union in New York, where she works as an art professor.

Roads & Kingdoms: Was this your first time to Kyrgyzstan?

Margaret Morton: Yes, and it wasn’t a country I would ever have thought to go to. The director from La Mama theater company had applied for a grant to do a research project on a Kyrgyz epic about a female warrior. She was planning to turn it into a play here in New York. As part of the research aspect of the trip, she asked me if I’d like to go to Kyrgyzstan and be the photographer on this project. It sounded really intriguing and I was up for an adventure so I said yes. I didn’t even know what she was talking about really in terms of how to spell it and where it was exactly on a map. Four months later, she called me and said: we got the grant. It was a real spontaneous trip. For six weeks, we traveled all over the country with a local theater group. As I was photographing the sites of this Kyrgyz epic, I started seeing these cemeteries and asking to stop the car. I did that as much as I could get away with, but I realized that I needed more time devoted just to the cemeteries. The night before we were to fly back, I asked if she could change my airline ticket. One of the Kyrgyz actors, who’s actually the stage manager, said I could come live with her aunt and her, so I moved into this household of women all cramped into this tiny Soviet-era apartment block. I hired a Ukrainian driver because he wasn’t hesitant about going near the cemeteries—the Kyrgyz are very superstitious, they don’t visit them. After four weeks, I came back and applied for my own grant, which supported me for two more years.

R&K: Do you remember the first cemetery you saw?

Morton: The very first one that I saw was on the south shore of Lake Issyk Kul. I absolutely remember it because they were the tallest tombstones that I ended up seeing, but yet they were very thin and flat. When we came upon them, they looked so majestic and then as we drove past, they completely flattened and I realized they were just facades. I was totally transfixed by the illusion, that something that monumental could be just a sliver.

R&K: Were you able to stop the car and photograph it?

Morton: Yes. I did a lot of that. We had a Kyrgyz art historian traveling with us so she explained a lot of the burial traditions. Many of the actors wanted to show me their own tribal cemeteries and when I went back the other two summers I did stay with a lot of their families. Even though they don’t traditionally visit cemeteries, they would take me there and I got to see the most remote ones that way. I stayed with Elmira Kochumkulova, who wrote the introduction to my book, at her family home on the Uzbekistan border. That was fantastic because we went to cemeteries we couldn’t even reach by car, we’d have to walk up a mountain for the rest of the way.

R&K: Are the tombstones and burial traditions changing these days?

Morton: Today we see more of simple mounds, which is the more conservative Islamic tradition. That’s controversial over there, but Elmira says she sees more and more mounds. In 2008, old traditional tombs were desecrated. The eyes of the portraits were gouged out. Elmira’s uncle said he heard that some young people had completely destroyed a family tomb [because Islamic law forbids elaborate markings on graves]. Ancestral cemeteries are not maintained, they’re intended to just return to the earth and over time. Elmira speculates that they won’t be nearly as visible in 10 years.

R&K: These cemeteries say so much about Kyrgyz history and culture, starting from animism and Nomadic traditions to Islamic and Soviet influences. Can you give examples of what this looks like physically?

Morton: Animism is present in the animal horns and the yak tails that are primarily on the Uzbekistan and Tajikistan borders. The deer horns are actually in the northern shore of Lake Issyk Kul because that region was settled by a group of people called the Deer People. Elmira had heard about them and her husband drove me there in 2008. We saw a lot of cemeteries and as it was getting dark, we stopped to look at one more and there they were. It was kind of eerie because it was in the semi-darkness and we saw these deer horns sprouting out of Islamic structures. Another specifically Nomadic tradition would be the metal yurt structures and the paintings or etchings of yurts. When someone dies, there’s a whole process where women lament for three days in a yurt, with their backs to the entrance. I actually saw this taking place in Bishkek in the middle of a Soviet block of apartments, in that square courtyard they always have. Suddenly this yurt appeared, so I knew someone in the building must have died. It’s a very somber scene and the laments are brutal. It’s very raw. The body stays there for three days, which is something that actually horrifies other Muslims I mentioned that to. Even Nasser Rabbat, who wrote the book’s preface, said: “three days that’s unheard of in Islam, you bury immediately!” So I had to have Elmira tell him. That certainly is the Nomadic traditions, also the men on horseback, the women serving tchai with the big headdress, the eagles…

Animals just start to graze and snakes bask on these mounds of dirt.

R&K: What about the Islamic and Soviet influences?

Morton: The Islamic influence is clear in the architecture, the domes and the star and crescent. There’s a very obvious and direct reference there. The Soviet influence is more frequently revealed in the enamel portraits, which are an Eastern European tradition. And of course there’s that one image where there’s a hammer and sickle with the star and crescent. I did not see a lot of that, that was really incredible. In another photograph, you see everything: you see the star and crescent, you see the animal horns, the Soviet military star and the islamic architecture.

R&K: So one cemetery can have all of these things at once?

Morton: Yes. They coexist within the Kyrgyz people, who don’t see all these separations. They see it as part of who they are. And then, the fact that the cemeteries are set in these beautiful mountain settings is just extraordinary. The Kyrgyz really respect nature. They don’t kill animals except for food. One of the 40 great Kyrgyz epics is about that, about a hunter who killed a goat for the sport, and then he was led to the edge of a cliff by a goat. You can’t live if you violate that respect for the animal.

In Kyrgyzstan, people build their tombstones themselves.

R&K: You mention that these tombs are supposed to disintegrate over time and go back into the earth, no one goes to visit these places?

Morton: They really don’t. Some of the more modern Kyrgyz will go once a year, there’s one day where you can go claim the weeds from the graves or the animal dung. Because animals just start to graze and snakes bask on these mounds of dirt. There is life in these cemeteries but not human life. But nobody I spoke to [goes for visits].

R&K: Is this the first time you’ve worked on a project about burial sites?

Morton: Yes it is. But my four previous books were also about alternative built environments. They looked at the houses that homeless people create for themselves in New York. In Kyrgyzstan, people build their tombstones themselves. The metal ones are more complicated to make, but it’s still going to be the local handyman who does them. It’s not a big industry. In the larger regional centers, there are places that make monuments, but not this type, it’s more something that’s been introduced with all the trade from China—black granite. It wasn’t that interesting to me really. Usually people are just making tombstones out of the mud of that cemetery. There’s something about that process that fascinates me. It’s very pure. They make it from that land and then it returns to that land.

R&K: It’s fascinating what the way we bury our dead says about us. In the book you mention that during Soviet times, they banned religion but they really didn’t touch the burial process…

Morton: No they didn’t. They destroyed a lot of very important mosques but they never touched the cemeteries. I mean, we all have the same destiny. I think how you respect the people who’ve gone before has a lot to say about you as a culture and as a civilization. And I think when the dead aren’t respected, that’s often the demise of a civilization. There certainly are cultures that, no matter what happens, make sure their dead are buried. I always respect that when I see it. Look at the students in Mexico that just disappeared, their families are so desperate. It was even on the radio this morning: “until we see the body we’ll never believe that our son is dead.” I don’t think any culture is casual about death. Even with the airplane that just came down, it’s a huge loss to people when they can’t reclaim the bodies of the dead. I don’t think anyone can say that’s okay. It’s part of being a civilized society.

You can buy “Cities of the Dead” here.