Hunting the fabled Cockentrice in Britain’s 1,000-year-old meat market.

There are four days until Christmas. It has just gone six in the morning, I’m in the heart of the City of London, and I’m wondering: How do you tell a good quality pig’s head from a bad one?

There are three left in the display cabinet, their dead eyes judging me judging them. I look to the butcher, a balled fist of a man clutching a vicious blade. I want to ask him which head he would recommend, but worry that would mark me as even weirder than I already feel. Likely one pig’s head’s as good as another.

“So, who will it be then?” he asks.

His voice is full of impatience, which doubtless builds in the couple of seconds it takes me to realize that when he said ‘who’ he meant the heads. I point to the least misshapen, least hairy of the three, i.e. the one that looks most like a pig.

“That one, please.”

“So you want the pretty boy, then?” the butcher grins and reaches into the cabinet to withdraw said ‘pretty boy.’ He drops the pink-grey head into a plastic bag: “Anything else?”

This is Smithfield Market, the biggest wholesale meat market in the UK, a supermarket of animal parts impossibly located amid some of the most expensive real estate in the world. Every night it is a factory of cutting and blood. It is too grotesque for modern London to put up with in the daylight; for the general public to shop here, they must arrive before dawn.

Needless to say I did not drag myself out of bed for a pig’s head alone, even a pretty one. I am hunting Cockentrice. The idea to attempt this medieval dish (delicacy is too fine a word) was born out of a desire to reinvigorate our Christmas roast. My friends and I had been discussing how easily the festive season can beget turkey fatigue and decided that this year our traditional pre-Christmas Christmas dinner needed a more inspiring, not to say, unusual main event.

With the head of a pig, the body of a capon (a castrated rooster) and a tail of goodness-knows-what, a Cockentrice was certainly that. This unlikely combination of fine dining and rogue taxidermy originated in the English cookbooks of the 14th Century, and was roasted as the centerpiece of kingly banquets, delivered to the dining hall like some slain mythical creature amid fire and song. There was, though, only one place in London where I was sure that all of the beast’s constituent parts could be found.

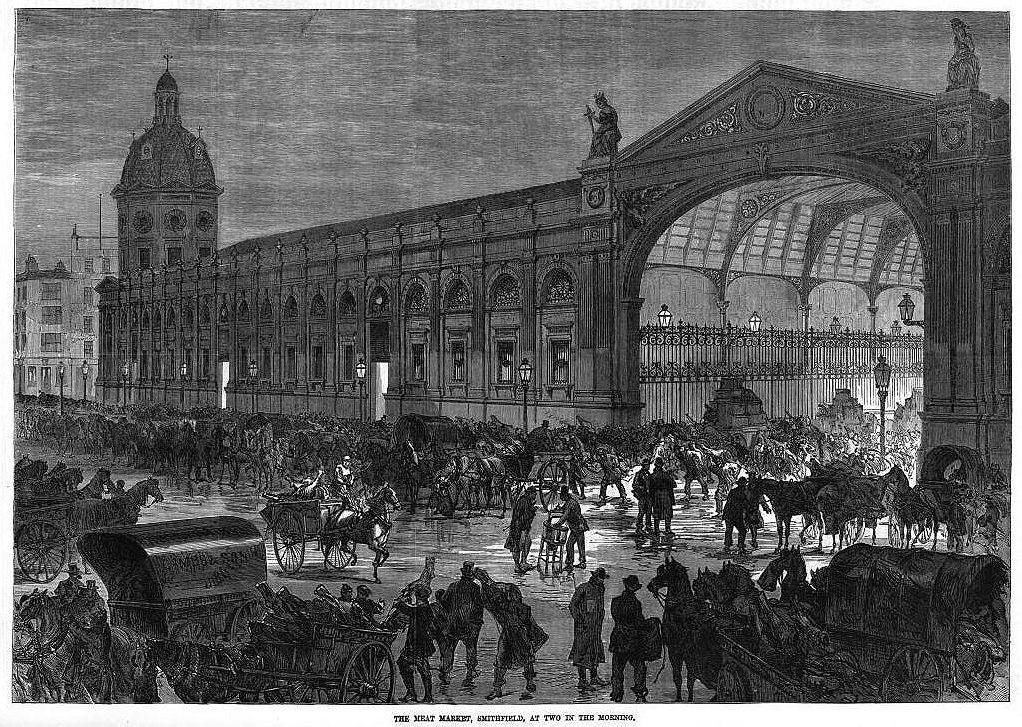

Smithfield Market has a pedigree even older than the Cockentrice. While its current butchers’ incarnation dates back only as far as the mid-19th Century, livestock has been traded here for almost 1,000 years. Originally named for being a ‘smooth field’ outside London’s walls, the area played host to city entertainments – jousts, dances, hangings (William Wallace, latterly of Braveheart fame, was put to death here in 1305) – then began to double as a livestock market some time in the 1100s.

While over time the city expanded, the market remained. In fact, Smithfield was a livestock market right up until the mid-1800s. At its peak in the Victorian era over 220,000 head of cattle and 1.5 million sheep changed hands here every year. In the heyday of the industrial revolution, the heart of London resembled a manic farmyard.

Even today, the absurdity of the market’s squeezed location is immediately apparent. A coronary of white vans clog the roads surrounding its elegant 19th Century colonnades (designed by the architect who built Tower Bridge, Sir Horace Jones) and closer still, there tussles a claustrophobic frenzy of forklifts, people, and meat.

The soundscape is of idling engines, bleeping industry, and coarse shouts. The smell is of cold blood. As I walk closer I am put in mind of a motorway pileup, or the aftermath of a battle. This is not meant for tourists.

It is though, a place where the spirit of London runs strong. For despite the excess of modern development that surrounds it – the chain shops, the glass and the chrome – there is something that feels very old about this part of the city. While many other European towns, particularly in the continent’s south, may have their heritage better preserved than London, they can often feel like museums.

In London, in the central square mile that forms the City of London in particular, history has been bludgeoned so hard it has become a ghost, and thus so much more affecting. It haunts the street signs, the banks of the river Thames and the very early dawn. It is the ideal location to search for a medieval meal.

Long plastic flaps curtain across the entrance to the market’s main arcade. Shouldering through them I walk into the biggest butcher’s shop I have ever seen. In fact, it is many different butchers’ shops, all selling slightly different produce, the variety of meats is remarkable. The uniforms of the butchers, though, are the same: white, with many spattered in blood.

Primarily a wholesale market, there are few concessions to more squeamish shoppers, and none of the hashtags or slogans of modern commerce. Most counters back directly onto their storage facilities, and are separated from them only by glass. It is a rarely offered backstage reveal of the butchery theatre, with whole hanging carcasses displayed like pink coats in an over-stuffed wardrobe. The blood smell is stronger too. It is a raw steak raised up close to your face: a clean smell but one that has the potential for decay. You feel it at the top of your nose.

A Cockentrice does not require that many ingredients (I settle on trying to find a beef rib for its tail). Nevertheless, it becomes apparent that I won’t be able to find them all at the same cabinet. So I move on from the pork specialist, taking the head with me.

Smithfield is not all offal and off-cuts, but I am drawn to the unusual, to the counters that look more like medical anatomy displays than offerings of things to eat. I talk to a young butcher who tells me his name is Justin. In the counter, beneath his folded arms is a pile—literally a pile—of hearts (which animal they belong to, I have no idea, if I didn’t know better I’d say they were human.)

I ask Justin if he sells many. “Course,” he says, “‘round this time of year ‘specially. We sell bundles of hearts.”

Later, I talk to another, more senior butcher: his position marked by the fact that his overalls are not covered in blood. His name is Oliver Absalom, director at Absalom & Tribe. I ask him the question that has been plaguing me all morning: how does it work? How does a wholesale market continue to function in the very heart of an area given over to finance? Don’t the banks want it to leave?

Absalom admits that Smithfield’s continued success remains a mystery, and that there’s often talk about moving the market to a less central location.

“But, then, this place does have a sort of magnetism to it,” he says. “And because we’re right in the middle of everything it means buyers can come from all directions, from every corner of London, and even beyond. So there is a kind of practical reason to it.”

But a central location does not come cheap. The rent on Absalom & Tribe’s counter space is £100,000 a year, and buying it is not an option. Fortunately the meat trade does not show any signs of slowing.

Absalom & Tribe cannot sell me the meat that I’m looking for. Their trade is in more traditional cuts – a lot to kebab shops, Absalom tells me. I am directed to more specialist butchers, and in the smorgasbord of Smithfield my hunt for the other parts of my Cockentrice does not last long.

I leave the market building clutching the pig’s head, a decent sized capon rooster, and a rib of beef. I step back into modern London, where an orange dawn is just cresting the surrounding skyscrapers. Then I go for a beer.

As well as warping one’s sense of which century it is, Smithfield plays havoc with your perception of the time of day. The expertly carved and displayed meats that pile the pre-dawn counters are the product of an entire night’s work. And like workers the world over, come the end of their shift, the butchers of Smithfield go in search of a drink.

A pub on Cowcross Street, with its morning opening hours, has been obliging them for generations. Its name, perfectly inappropriate for an establishment that specializes in dawn drinking, is ‘The Hope.’

I enter with my bag of disparate animal parts clutched innocently in one hand, and walk to the bar feeling uncomfortably like a serial killer. My awkwardness must show, as before I know it, I’m being heckled from a nearby table; a group of punters are inviting me to join them for a drink. Keen to talk to more people who work at the market, I accept.

But these are not butchers; they are construction workers, fresh from a nightshift in the tunnels of Crossrail, London’s new multi-billion pound subway expansion. The project, scheduled for completion in 2017, will link the West side of the city with the East.

It is an emblem of modern London: representative of progress at any cost, drilling blindly through layers of the city’s history. At Smithfield, there were fears that that history may fight back, that Crossrail’s tunnels may break into a famed 14th Century mass grave of victims of the Black Death. That it would release the anthrax spoors buried in the plague pit into the outside world.

Yet despite this potential for the area’s history to bite back, the Crossrail project is set to leave the main market largely intact. And so Smithfield’s unlikely success story continues. Indeed, the new train line may bring more customers to the area. Might the future of this wholesale meat market involve accommodating tourists after all?

I’ve got fifty-two steaks in my freezer at home

When I ask the workers, though, if they are aware of any negative effects Crossrail may have had on the Smithfield area, they are fast to come to its defense.

“It’s the biggest construction project going on anywhere in Europe,” one tells me, proud to be a part of such an event. “An’ all the men workin’ this part of it, they buy their meat from the market.”

“Yeah, the butcher boys love us,” says another. “I’ve got fifty-two steaks in my freezer at home.”

“Fifty-two?” I echo; this seems like an unnecessarily high number.

“You tell me if I could afford fifty-two steaks from a plain supermarket.” I shrug. “I couldn’t,” he says.

I am already feeling carried away, thinking how these men, hard at work on one of London’s ultra-modern businesses, are connected with Smithfield, one of its oldest.

“And Dave here, he even buys a couple of pigs heads every week from the market, don’t you Dave?”

I look to Dave. He has been silent since my arrival at the table. He’s one of Crossrail’s designated ‘black hats,’ a foreman on the project. He is broad and middle aged, has a raised scar on his cheek, and arms that are intimidatingly crossed over his chest.

“Really?” I ask him, excited now. The centuries feel like they’re cramming into each other: I’ve met a Crossrail worker with medieval tastes! Also, it occurs to me that I can perhaps I can get an answer my question about how to judge the quality of a pig’s head.

“No,” Dave growls. “Sydenham Nick’s having you on. But I do buy a lot of sausages.”

Outside The Hope, time summersaults back the right way again. Dawn has broken now, and London is revealed in its gleaming modernity. A flow of cyclists and suited commuters are rolling past me, ignorant of all the blood so recently spilt nearby. The activity at the market has almost ceased.

The only butchers left are the younger ones, and rather than heading for The Hope, they are queuing to get into a Pret a Manger— a trendy, somewhat health-focused sandwich chain. After a night tussling with meat, perhaps I’d want a whole-grain super greens sandwich too.

With daylight, the ghosts of London’s history depart. So, I too head home with the Cockentrice, thinking how this evening I will again cook up the past.