Tatars fleeing the annexed peninsula are bringing their culture to the rest of Ukraine.

Crimea has seemed like an exotic place to me since I was a child. It was the land of sunshine, sea, and mountains; most of all, it was the land of the Tatars. They looked different from the rest of us Ukrainians. They spoke a different language, belonged to a different religion, and cooked a different kind of food. Going to Crimea was like taking a trip abroad, except that you didn’t need to speak English to be understood and no visa was required.

From early May until late October, the trains bound to Simferopol—the regional center—were packed like cans of sardines. You had to buy the tickets a few weeks in advance to get even a basic third-class sleeper bunk. My parents brought me to Crimea mainly for health reasons; it was widely believed that Crimea’s subtropical climate could prepare a child for another frigid Ukrainian winter. I didn’t think much about the health benefits of those trips, but I enjoyed them all the same. I was excited about camels strutting along the waterfront. I adored spending time in Bakhchysarai, the former capital of the Crimean Khanate. I gawked happily at the old palace of the Khan and the brightly colored crafts made by local artisans. And then there was the food.

All year, I longed for a taste of local pakhlava, a honey-colored pastry oozing sticky sugar syrup. As I found out later, local pakhlava is similar to its cognate, Turkish baklava, but with a few key differences. Whereas baklava is made of several dozen thin layers of dough interspersed with nuts, pakhlava is made of only a few thick, twisted layers of dough. Both of them are soaked in sugary syrup or honey, causing them to melt in your mouth. It was to die for, and I envied Tatar children who, I imagined, could eat it every day.

EVERYBODY TURNED A BLIND EYE TO THE EXCESS OF OIL AND SUGAR

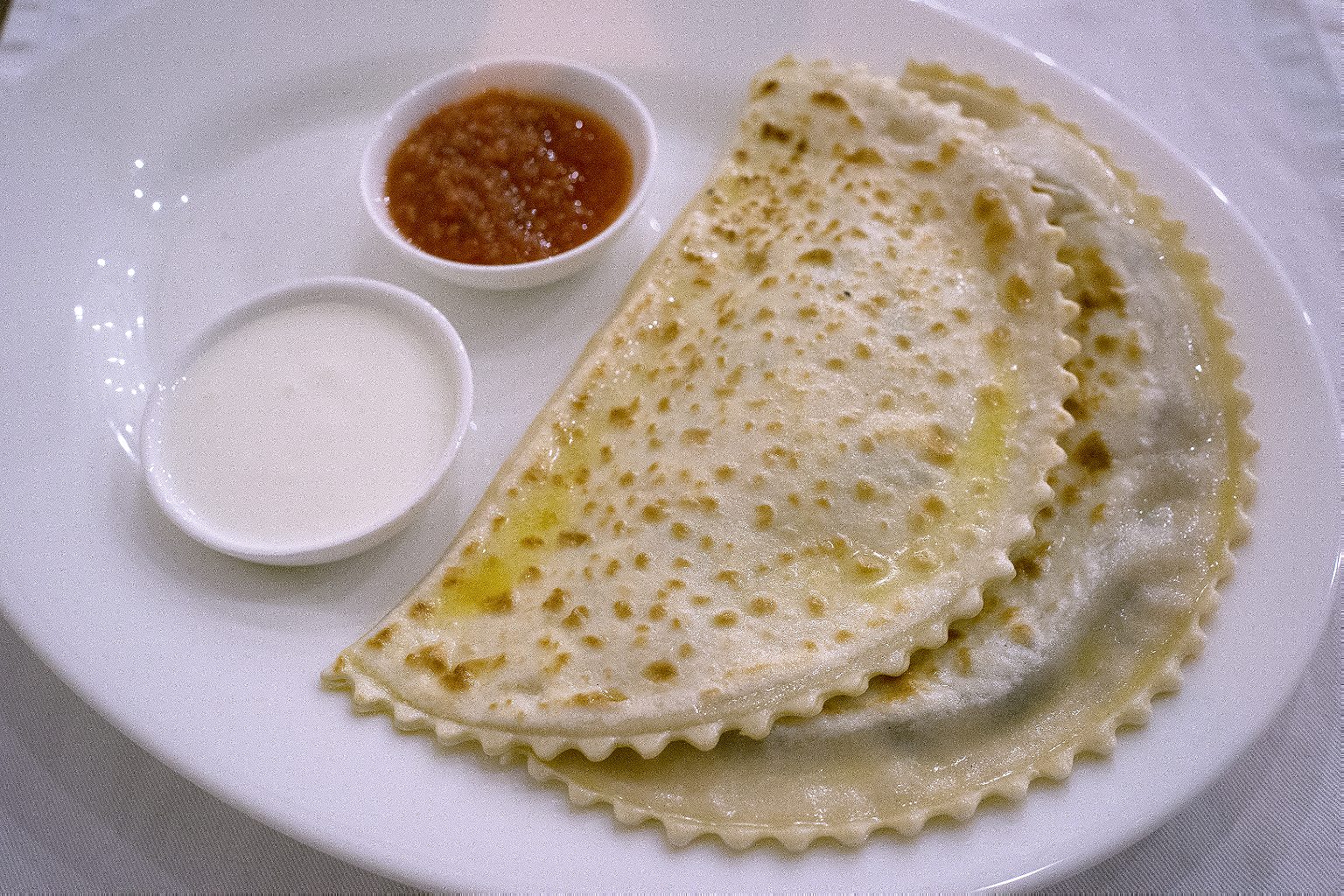

Only one other dish could rival the joy of pakhlava: chiburekki. Chiburekki are deep-fried turnovers filled with minced mutton or beef mixed with onion and spices. The best chiburekki are those made to order, right in front of the customer’s eyes. The cook rolls dough into a thin circle and puts a dollop of filling on one half before sealing the pastry into a half moon. These half moons are then deep fried and served scalding hot. Ideally, they should be dry and crispy on the outside and juicy and soft inside.

The dishes are as unhealthy as they sound. But everybody turned a blind eye to the excess of oil and sugar: most people could only treat themselves to this exotic combo once a year, after all. There was no quality Crimean Tatar food to be found elsewhere in Ukraine; not the kind of Tatar food that would make you feel transported four hundred miles to the south.

So, imagine my surprise when I saw real Tatar cooks serving original Tatar pakhlava and chiburekki in the Ukrainian capital city of Kyiv, far from the Crimean seaside. As I walked down a city street, I spotted a small kiosk churning out deep-fried half moons of chiburekki and their grilled variations, called yantiki. Customers formed a long line, attesting to the food’s authenticity.

The reason for the recent spread of authentic Tatar cuisine around Ukraine is far less pleasant than a plate of chiburekki. In the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution, the Russian Federation annexed the Crimean Peninsula. First came the arrival of the so-called “polite people” or “little green men”: masked militants without insignia who occupied strategic sites on the peninsula without firing a shot. The pro-Russian government was then established and an unconstitutional referendum was held, the result of which was the proclamation of Crimean independence and its integration into the Russian Federation.

Since the annexation, tourism in the area dwindled, and with it a vital source of income for the Tatars, as well as the rest of the Ukrainian population on the peninsula. Many residents preferred to stay, but others decided to try their luck somewhere on the mainland. Kyiv became the city of choice, and a few Tatars began opening small cafeterias as well as full-fledged restaurants. These establishments are easily recognizable by the two flags hanging by the door: one is the blue and yellow flag of Ukraine, the other, the yellow on sky-blue flag of the Crimean Tatars. The two flags hanging side by side are a symbol of support and unity between the Tatar population and the rest of Ukraine. The owner of a small Tatar cafeteria, Burma—named after a rolled Tatar pastry—near the Demiyevski green market, keeps a low profile, but at the same time actively promotes the rightful place of Crimea within Ukrainian borders. (The owner asked not to be identified by name in this article.) A slogan on the window of her eatery reads: “Crimea is Ukraine,” a popular slogan among supporters of Ukraine during the Crimean crisis.

She, like many other Tatars, didn’t encounter any problems registering her business outside of Crimea, which many of those attempting to relocate see as a sign of support from the Ukrainian government. At the same time, the Tatars don’t see this move as a solution to their problems. They still consider Crimea to be their home and plan to return as soon as it is possible to live and work there safely and without obstructions from the new regime. “Our ancestors have lived outside of Crimea for too long,” says Emine Emirsalieva, the owner of a recently opened Tatar restaurant Musafir. “If we all move out, who will stand for our land?”

Crimean Tatars trace their history back to the Mongol invasion of Europe, when several clans of the Golden Horde Empire decided to stay in Crimea and make it their homeland. There they mixed with the local tribes and formed a separate Crimean Khanate. With the spread of the Ottoman Empire to the north, the Khanate became the Turkish sultan’s vassal state. As descendants of the Golden Horde, the Crimean Khan was allowed to rule the southeastern plains of Ukraine, which he did till the annexation of its territory by the Russian Empire in the eighteenth century. At that time, many Tatars preferred to emigrate to present-day Turkey, Bulgaria, and Romania. Many of those who stayed were deported by force after the end of the WWII to Central Asia, namely Uzbekistan.

Only in November 2015 did the Ukrainian government acknowledge that the forced deportation of the Crimean Tatar population was an act of genocide and pass laws to support the preservation of Tatar culture in Ukraine. The statement was announced as a response to recent discrimination, persecution, and suppression of freedoms of the Tatar population in Crimea by the Russian government. The leader of the Crimean Tatars, Mustafa Djemilev, states that around 10,000 Tatars have emigrated from the peninsula since the most recent occupation of Crimea.

Emirsalieva remembers those times of exile with pain in her voice. Her family still lives in Crimea and doesn’t want to leave, even though their family restaurant in Bakhchysarai was forced to close. Her husband moved to Kyiv five years ago for professional reasons, but it is only recently that they decided to open a restaurant here, after their restaurant in Crimea was closed.

“We saw the niche for our type of restaurant in Kyiv, so we decided to give it a go. We try to preserve the same style in decoration as in Bakhchysarai and we invited the cook that worked for us there so that she could train the cooks we found in Kyiv,” she explains.

The personnel in Musafir are a mix of Ukrainians and Tatars who were forced to emigrate from Donbas and Crimea, but after training, they manage to successfully create authentic Crimean Tatar dishes. They even prepare coffee in hot sand and serve it Tatar style: in a jezve, a small pot designed to make Turkish coffee. “We added some vegetarian variations of chiburekki and yantiki because there are many vegetarians in Kyiv,” says Emirsalieva. “And after many discussions we decided to put beer on the menu,” adds Sorina Seitvelieva, her partner and sister-in-law.

The decision to serve alcohol is a contentious one because Tatars, unlike the majority of Ukrainians, are typically Muslim. All of the food at Musafir is halal, one of the traditions they are trying to preserve. Besides providing the new settlers with jobs, Musafir has become a center of Tatar culture. They organize events where traditional Tatar music is played and hope to become a place for Tatar craftsmen to present their work. Local Tatars drop by for a dinner or gather to celebrate birthdays and holidays. According to Emine, they prepared iftar—an evening meal served during Ramadan—this year, and also celebrated Kurban Bayrami—also known as Eid al-Adha or the Sacrifice Feast, during which every family slays a lamb— by sharing pieces of cooked lamb among their employees.

“One of our former cooks from back in Bakhchysarai has recently moved to Kyiv and opened a chiburekki shop near Volodymyrski market, in the center of Kyiv. But he comes here from time to time for a meal,” says Seitvelieva. “We are still friends.”

Tatar cafeterias and kiosks in Kyiv are strategically located near the green markets and in the vicinity of universities. Students, shoppers, and vendors grab freshly cooked food and eat it on the go, while cooks keep on rolling the dough and sculpting more pastries. Large restaurants serving Tatar cuisine remain rare. There are only two of them in Kyiv, located far enough apart that they can barely be called competitors. The market is not yet saturated enough to create tension; for now, there is a sense of solidarity among the community. The Tatars are viewed not as intruders in Kyiv but as those persecuted by a hostile regime and in need of support.

Though the annexation of Crimea is painful for both Tatars and the rest of the Ukrainian population, they can come together to enjoy a piece of Crimean life, albeit far away from the sea and the mountains of the Ukrainian south. In Kyiv, for now, all they can do is proclaim the brotherhood between their two peoples over a plate of chiburekki.