Last year, two young Jewish Americans began leading educational tours of the troubled Palestinian territory. But their ambitions are bigger than a bus trip.

WEST BANK—

Last year a friend and I started Extend, an organization that offers young Jewish Americans visiting Israel the opportunity to go on a five-day tour of the West Bank. Every year, tens of thousands of college-aged Jewish Americans visit Israel—on vacation, on programs like Birthright, for internships. We wanted these young people to have the opportunity to meet Palestinians during their time in the region, to learn about Palestinian history and day-to-day life, and explore the diversity of Palestinian views on the conflict.

There are many programs that ferry young Jewish Americans from the U.S. to Israel, but not many take them the next few miles into the West Bank. My co-founder Sam Sussman and I devised a fairly simple plan: Hire a bus and arrange a thorough tour of the West Bank with Palestinian locals. First we put the word out to see if young Jewish Americans were interested in coming along. They were. In our first year of operation we ran five tours and took nearly 60 young people along with us. Through running these tours, I’ve become convinced that our generation of Jewish Americans sees this conflict radically differently than our parent’s generation. We want to engage directly with Palestinians as players of equal standing in a tragic conflict. That is no consolation to the millions of civilians trapped in the current fighting, but perhaps it’s a tiny glimmer of hope.

Organizing the tours proved relatively seamless. There were a few Palestinian and Israeli civil society organizations with whom we wanted to work. We called them up and asked if they were interested in speaking with our group. Almost all said yes.

The tours started off in East Jerusalem, where we learned about Palestinian heritage in the city, and spoke with experts about the municipality’s demolition of “illegally built” Palestinian homes. We headed into Hebron, where we were given tours of the city—Palestine’s largest, with a Jewish settlement directly in its center—led by Breaking the Silence, an organization of former Israeli soldiers who are critical of the missions they were asked to carry out for the Israel Defense Forces.

Afterward we went into the settlement to meet the settlers themselves and learn about their lives and why this land is important to them. We spent the rest of the day with local Palestinian organizations. We listened to local Hebron residents tell us about how their city had been squeezed by the Occupation—Shahuda Street, once the busiest street in Hebron, had been closed to Palestinians, shops had been relocated or shut down. Later, we met with the leaders of protest movements in Nabi Saleh and Bil’in, and spoke with Palestinian businesspeople and entrepreneurs about the challenges of starting a business under the Occupation. Speaking with Military Court Watch, a legal organization that monitors the IDF’s detention of Palestinian children, we learned about the separate West Bank legal systems for Palestinians and Israelis, and how Palestinians who are accused of crimes are tried in military, not civilian, courts. We talked about the future, and how our speakers expected the situation would evolve.

Throughout the tour we lead seminar-like discussions about the stories we were hearing, discussing questions like why settler accounts of the conflict differed so much from Palestinian accounts, and where the differences came from.

The most compelling moments of the tour, however, were the ones we couldn’t plan. On one tour of Hebron, a Palestinian man who was trying to sell the group trinkets was detained by Israeli soldiers. When a student asked how long the man would be detained, the Israeli soldier said, “For as long as we think he should be.”

There is no easy way to summarize how young Jewish Americans react to spending time in Palestinian communities. The students who come with us tend to enter the West Bank curious and skeptical and to leave the same way. They aren’t naïve and they aren’t extremely shocked when they hear criticism of Israel. Often participants will discuss how the debates about Israel’s conduct—detention of detainees without trials, military overreaction to terror attacks, racial and religious profiling—mirror post-9/11 debates that still haven’t been resolved in the United States. The debates in the West Bank may feel more urgent, but they are not unfamiliar.

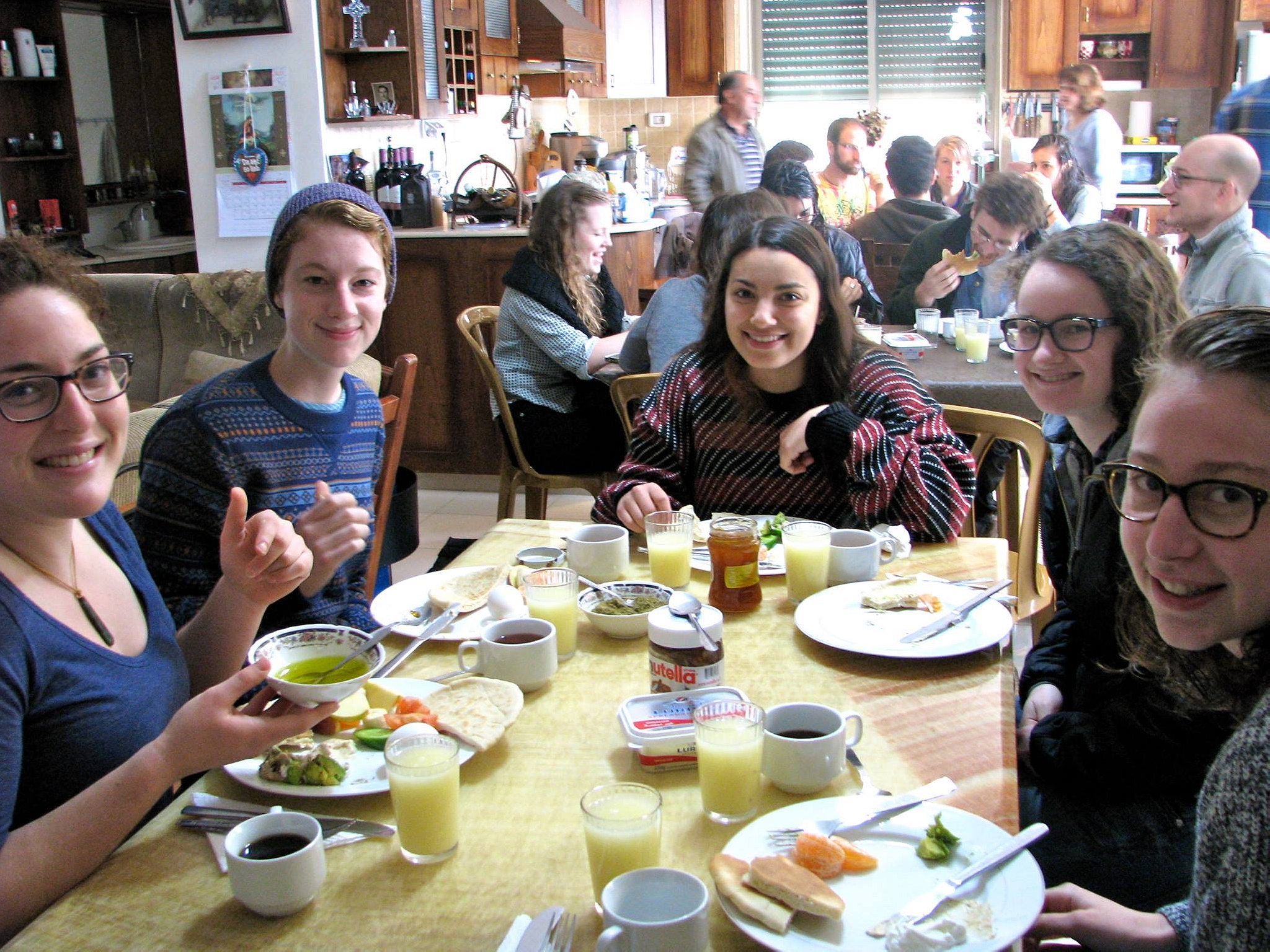

The Palestinians we meet are uniformly gracious, serving us sweet tea and pita bread, and handling pointed questions with aplomb. Many Palestinians we work with have told me that they have complex emotions about chatting with Jewish groups from the U.S. On the one hand, they are grateful we are coming and listening to their stories. They understand that for many of our participants deciding to spend five days in the West Bank is a brave step, and one that may put them at odds with portions of their community back home. They are pragmatic and know that our voices matter in the U.S. On the other hand, many Palestinian speakers confess to me that they wish their civil rights weren’t at all dependent on how Jewish American twenty-somethings judge their situation. They long for a world where they won’t have to plead their case to well-intentioned people—Jewish or non-Jewish—who possess political power but will never fully understand their reality.

There are a few things we hope all of our participants will take away with them. Most can explain why Jerusalem is a city of extraordinary importance to both Jews and Palestinians, and how the 1948 war meant something very different for Palestinians than it did for Israelis.

This knowledge allows participants to sensitively collaborate with Jewish and Palestinian activists when they return home. Many of our participants, when they return to their universities, have taken leadership roles in organizations that work to create an autonomous future for both people. Others have given talks about their time in the West Bank at their local synagogues, or have decided to study abroad in Israel and join local organizations dedicated to finding a peaceful solution to the conflict.

A LONG-TERM POLITICAL SOLUTION TO THE CONFLICT SEEMS IMPOSSIBLY FAR AWAY

These are awful times in Israel and Palestine. Gaza has been bombed to rubble; Israeli life is regularly interrupted by rocket and mortar fire. Hamas has proven extraordinary belligerent and its rhetoric is toxic. Israeli President Benjamin Netanyahu made clear, during a press conference on the fourth day of fighting, that he does not support any commonly understood version of the two state solution—that Israel will always maintain “security control” of the West Bank. A long-term political solution to the conflict seems impossibly far away.

Some good news amid all this is how active members of the Jewish American community’s youngest generation have been in reaching out to Palestinian partners and affirming their believe that violence is no solution. Last year saw a proliferation of grassroots Jewish movements, spearheaded by young Jewish Americans, designed to bring Palestinian perspectives into the American-Jewish conversation about Israel and Palestine.

Open Hillel is a movement that agitates for college Hillels—Jewish centers that host Jewish celebrations and events—to allow Palestinians who support boycotts against Israel to speak at Hillel events. It’s already had some success; during the last academic year a number of college Hillels declared themselves “Open Hillels” and rejected the restrictions placed on who is allowed to speak. In response, Hillel’s CEO has called for a review of its partnership guidelines, acknowledging that policies “haven’t been updated or modernized.”

When the most recent fighting started, a group representing young Jewish Americans called If Not Now, When? sprang into action in New York City, publicly reading the names of the Palestinians and Israelis who have been killed in the latest round of fighting. In Israel, All That’s Left, a grassroots anti-occupation group formed largely by young Americans living in Israel [disclosure: I’m a member], has actively protested the violence.

The American Jewish community still has incredibly far to go in incorporating Palestinian perspectives into its discussion about Israel and Palestine’s future. Statements from the Conference of Presidents of American Jewish Organizations issued over the past few weeks consistently reaffirm American Jewish solidarity with the suffering people of Israel, but neglect the suffering of Palestinians, as if the fighting is exclusively one side’s fault, or one side’s deaths are more tragic.

I THINK A RECKONING IS COMING

Nonetheless I believe that the gap in views between my generation and my parent’s is bridgeable. When I spoke about Extend this February at Temple Israel, the Conservative synagogue in New Jersey where I was raised to love Israel as a child, I was petrified about how the congregants would interpret my activism. I sat in the pews, toward the back of the room, nervous, feeling like it was my Bar Mitzvah all over again. As people filed in, my mom whispered things in my ear like, “She really is not going to agree with you” or “I know that family, they’re not going to like what you have to say.”

But afterward most of the congregants who showed up to services that Friday evening seemed to agree that Jewish Americans didn’t know nearly enough about Palestinian life, and that it was to everyone’s detriment. One person who my mom insisted would not be sympathetic to my talk came up and congratulated me afterward. She told me that her niece had lived in Israel and spent time with Palestinians in the West Bank.

She came back disturbed by the separate legal systems, and convinced that Palestinians needed a state of their own. The niece helped change her entire family’s views of the Occupation. It’s a story I’ve heard many times since launching Extend.

I think a reckoning is coming. Young Jewish Americans grew up with a different Middle East, one where Israel’s military was dominant and American hawkishness caused terrible hardship. It seems obvious to many of us that any long-term solution to the conflict is going to involve accepting Palestinians as equal partners. It won’t be long before mainstream Jewish organizations will start to listen. But even if they don’t, the current violence will eventually let up. Then there will be more buses, and more opportunities to connect and improve the situation.