Inside the bizarre subculture that lives to explore Chernobyl’s Dead Zone.

IVANKIV, Ukraine—

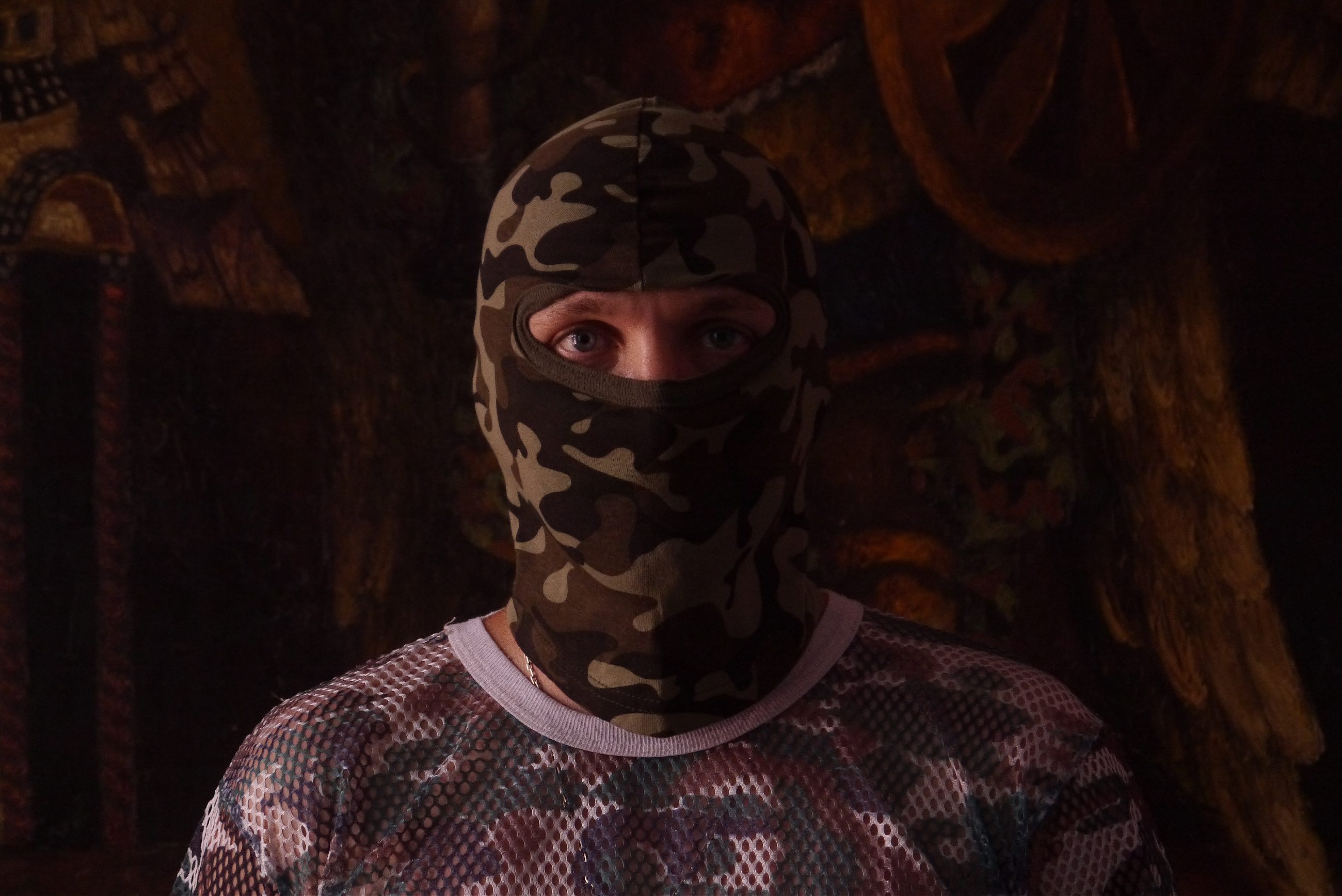

A teenager in green and black paramilitary gear is speaking Russian in a hushed, low voice. An overgrown graveyard is barely visible off to the right of him. Traditional Ukrainian cloths hang on a few crosses. A white stork passes overhead.

“This should be the cemetery,” he says. “We got to the exact spot we were aiming for.”

He puts away his GPS. He holds his hand-held Geiger counter up over a mound of dirt that covers radioactive machinery; the beeping goes wild and the numbers shoot up. 1.1.7, 1.1.8, 1.1.9. “This is beyond the scale,” he says, half-scared and half-thrilled. He moves away from the spot. The carcass of Chernobyl’s Reactor No. 4 punctuates the distance.

On April 26, 1986, the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant’s Reactor No. 4 exploded, and the ensuing nuclear fire burned for 10 days, releasing 400 times as much radiation as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. A radioactive rain of cesium, plutonium, and strontium blanketed parts of Ukraine, western Russia, and Belarus. Twenty-eight years later, Chernobyl remains the world’s worst nuclear accident. (Caveat: The Fukushima disaster is still playing out.)

The long-term effects and death toll of Chernobyl are controversial and hard to quantify. The World Health Organization expects a total of 4,000 deaths linked to the event, including those who died in the initial disaster and cancer cases that have developed and will develop afterward. Other organizations, such as Greenpeace, contend that the health hazards have been wildly underestimated and that eventually the death toll will hit nearly 100,000.

It will be generations before the consequences of Chernobyl are fully understood

The fallout was political as well. The Soviet Union’s inability to deny or control the story of the disaster arguably represented the first cracks in the superpower’s totalitarian myth—cracks that would widen into glasnost and within just a few years shatter the Soviet state. It will likely be generations before the consequences of Chernobyl are fully understood, and we are only one generation into what will be a centuries-long nuclear parable.

As the first generation of Ukrainians born after the Chernobyl tragedy comes of age, a small subculture of them is now doing the unthinkable: defying government prohibitions and illegally entering the highly radioactive Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, or “Dead Zone”—for fun. This group is monitored and pursued by the police and not fond of journalists: They curry in the forbidden, recover meaning from Soviet detritus, and take digital appropriation to new extremes. “It’s a post-apocalyptic romance,” as one young man put it.

V. is standing in front of a barbed wire fence, looking left and right, his head down. He is nervously entering near a militia post, a place where arrests happen frequently. He opens a flask and takes a shot of vodka, as is his tradition, anointing this trip into the Zone. He shimmies under the bottom strand of barbed wire and gets to the other side then holds it up for his friend.

“This is your first time in the Zone, right?”

“Yes.”

“Congratulations.”

They get low and trot toward a tree-covered area off to the right.

Shortly after the accident, the Soviets declared a 1,000-square-kilometer Exclusion Zone uninhabitable, and mass evacuations began to take place. Nearly three decades later, the Zone remains among the most contaminated places on Earth, and at its center is the ongoing hazard of Reactor No. 4, with 200 tons of lavalike nuclear material underneath.

Just 3 kilometers from the reactor is the plant’s company town, called Pripyat. Today, the bleak radioactive ghost town’s abandoned apartment buildings slowly fall apart and pay quiet homage to the nearly 50,000 people who fled. Pripyat is full of still-lifes; a table set for dinner, a Ferris wheel squeaking in an elegiac, fruitless wait for children. Wild boar snuffle through rusted playgrounds, and kindergarten napping areas are scattered with wide-eyed, broken dolls, thick with radioactive dust. From the top of a high-rise, one can see “the sarcophagus,” 3 kilometers in the distance, covering Reactor No. 4, which sits cracked and rusted and wafting radioactive dust. Twelve-foot-long catfish swim in its long-defunct cooling pond.

For the “post-apocalyptic romantics” who have taken to sneaking into the Zone, a visit to Pripyat has become the Holy Grail. Like trauma victims returning to the scene of the incident, they come here for reasons they can’t fully explain.

V. makes his way past rusted, still bumper cars, surreptitiously; it is dangerous to move through Pripyat at dusk. Usually he goes only at night. He keeps his dosimeter off so as not to make noise and alert police who might be on patrol. V. walks into a nine-story building, up the rickety stairs and into an apartment with peeling flowered wallpaper and many shades of gray. “Dobryj den.” Good afternoon, he says to three young men who are already there. They had agreed in an online forum that this is where they’d meet. This is their hideout.

The term that has come to be used for those who sneak into the Zone is “stalkers.” It’s a word and a cultural type with deep resonance in this part of the world, first appearing in a 1971 science fiction novel called Roadside Picnic, by the Russian brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. In the novel there are “post-Visitation” (presumably by aliens) worlds in which “Zones” harbor inexplicable, deadly phenomena. The government tries to tightly regulate the area to keep a group of thieves called “stalkers” from sneaking in and taking out artifacts. In the book, stalkers must evade both the police and a strange array of invisible, deadly booby traps.

What the artifact-gathering stalker in Roadside Picnic truly wants is meaning and hope, represented by the wish-granting “Golden Sphere” that rests at the center of the Zone.

Eight years after the release of the book, Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky adapted it into the now-classic film Stalker. Both book and film became cult classics in the waning years of the Soviet empire.

Roadside Picnic and Stalker, created 15 and seven years, respectively, before the Chernobyl accident spread radiation throughout the region, also proved prescient: An apocalyptic event leaves behind an invisible force with the power to create mutants? It’s not entirely fiction, unfortunately.

They arrive at Rudnya-Veresnya after walking for several kilometers in the woods. It is a village inside the Zone that was evacuated, but not buried, as many others were. A cottage is overgrown with rambling bare wisteria vines, and a shed next to it is totally collapsed. They enter, measure the levels at the fireplace, and scuffle through decades of old debris; memories of a life—cursive postcards from a beach vacation, a notebook with a list on it—left in the wake of a hasty departure. They flip through old newspapers and find Communist Party ID cards. “It’s a time capsule,” says one visitor. “If you want to see how it was in the USSR 30 years ago, you can go to the Chernobyl Zone.”

In 2007 the stalker legend was updated for the digital age when a team of young Ukrainian designers released a post-apocalyptic first-person shooter video game they called S.T.A.L.K.E.R. (Scavengers, Trespassers, Adventurers, Loners, Killers, Explorers, Robbers), set in the Exclusion Zone around Chernobyl. “We had a dream to create a game based on the story of Chernobyl,” says Oleg Yavorsky, one of the game’s creators. “To help make the Chernobyl story well-known around the world—especially to younger people.” In the game, Chernobyl has experienced a second nuclear disaster. The player assumes the identity of an amnesiac stalker who navigates the Zone’s radiation-caused “anomalies”—altered physics, zombies, and other sci-fi-inflected hazards.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. caught on, and along with several sequels, has sold more than 5 million copies to date, mostly in Eastern Europe and Russia. It also spawned a subset of fans who were not content to confine their gameplay to the screen. Loosely organized squads of gamers began to experiment with breaking into the zone for real, living out the fantasy without the blessing of the game’s creators. “Many of the guys wanted to visit the real site after playing,” says Yavorsky. “We didn’t expect that to happen, of course. We were just trying to make a cool game.”

Since the Exclusion Zone was created in 1986, there have been isolated trespassers who’ve snuck in to loot. But today breaking into the Zone has become a true geek subculture, and for some, an obsession.

The young men have arrived at Skazochniy camp. They slowly walk across the field, past weather-worn blue picnic tables, measuring radiation levels. It was a “Young Pioneer Camp” where they were sent as children, like many children in socialist states across the region. They walk inside, through vast dormitory rooms, and crunch over the rubble-strewn tile floor. Huge swaths of dark pink paint hang, curled, off the sides of every wall; aggressive conifers punch through glassless windows.

The nuclear accident referred to in the region simply as “The Tragedy” may be hazy history for today’s twenty- and thirtysomethings, but it remains an open wound for their parents and grandparents, many of whom were affected directly. The scores of first responders to the accident were exposed to fatal doses of radiation and were Chernobyl’s initial victims. After them, robots tried to put out the fire, but the extreme radiation levels made the machines malfunction. Next, the Soviets brought in soldiers, who became known as “liquidators.” Thousands of these young men were presented with a grim choice: two years serving in the bloody Afghan war, or two minutes shoveling radioactive debris off the top of Chernobyl’s reactor. Most of them took a shot of vodka and opted for the latter. (Vodka was, and still is, widely believed by Ukrainians to combat radiation.) Most of the liquidators are now sick or dead.

One 14-year-old stalker told me, in hushed tones, how his grandfather was one of the Chernobyl plant’s control room engineers. The Soviets put his grandfather and his colleagues in prison after the accident. (Soviet officials blamed plant workers for the disaster.) “He got out a few years later and died of cancer. I never knew him,” he says.

Most stalkers hide their activities from their families; others do it in defiance of them.

One casually explained his status as a card-carrying “Child of Chernobyl” due to his exposure at a young age. “It allowed some privileges. We were sent to retreats and summer camps to rest and improve our health.”

“My grandfather fought the fire in the Zone for a month,” he continued. “He would not be happy if he knew I was going. He was there against his will. I go because I want to. It would be unimaginable to him.”

The stalker generation has grown up with a distrust of government and authority, first forged under Soviet rule and furthered in a post-Soviet era beset by corruption and economic turmoil.

Sex, drugs, and radiation

Another oft-cited piece of cultural fallout from Chernobyl is a pervasive fatalism; a widespread victim mindset, which creates a feeling of “lacking control over their future,” as Fred Mettler of the International Atomic Energy Association wrote in the report Chernobyl’s Legacy: Health, Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts. He adds, “The population remains largely unsure of what the effects of radiation actually are and retain a sense of foreboding. A number of adolescents and young adults who have been exposed to modest or small amounts of radiation feel that they are somehow fatally flawed and there is no downside to using illicit drugs or having unprotected sex.”

Sex, drugs, and radiation: Stalking might be seen as the adolescent acting-out of a generation that feels it’s got nothing to lose. But for many stalkers, it’s clearly something more.

V. puts his cap on backward and is taking off his shoes to cross a cracked asphalt road swamped over with water. Suddenly there’s a sound—Kacscchhhhh.

“Police? A Moose?” one of them whispers hoarsely. The boys take off running into the woods, barefoot, cursing from the pain to their feet, and the fear of being caught by the authorities.

“I knew we were close to a security post.”

They lay in the bushes, still and hiding, for 40 minutes until they know it is safe to make an escape.

Online communities have emerged to trade information, tips, and advice on what routes are safe from the police, which entrances have become too dangerous, or where supplies are hidden. Experienced stalkers sometimes mentor younger wannabes. Pseudonyms are always used. In-person meetings are only cautiously pursued, as stalkers worry about police sting operations.

Some forums are open only to those who’ve achieved a certain level of success. Stalkers pursue a set of thresholds—or “acceptances”—by reaching an increasingly challenging (and dangerous) set of destinations. “Dogs and security are the biggest problem in the Chernobyl Zone, not radiation, not zombies,” says one veteran who almost lost an eye while fleeing police.

I drink water in the Zone, eat apples…

Of course, radiation seems like the most obvious danger, though the health risks aren’t as clear as you might think. Nearly 30 years after an accident, nuclear contaminants with short half-lives are no longer a threat, and acute radiation poisoning would only take place if you “went into the sarcophagus and sat on the fuel containing rods,” says Chernobyl official Vita Polyakova. But there are still elevated background radiation levels in places such as Pripyat as well super “hot spots” of severe contamination, many of them undocumented. The risk of ingesting radionuclides—the radioactive strontium and cesium present in dust, water, and food grown in the area—is the most acute threat.

“Maybe on the outside we got more radiation than usual,” a stalker concedes, “but once we leave, radionuclides are washed off our skin and that’s it. The greatest risk is when it gets inside your body. That’s why we try to bring everything with us—water, food.”

“But D. ate apples in the Zone,” I remind him.

“I did, twice. They were so big!” D. chimes in. “I drink water in the Zone, eat apples, and everything is good for me. No second head,” he adds with a small smile.

“Before eating anything there is a stereotypical fear,” their friend adds, “but it goes away later.”

Among the stalkers I meet, their concerns for the risks—and attentiveness to radiation protocol—vary. Some use dosimeters, others don’t—or don’t trust them “There’s no guarantee the dosimeter will show a hot spot,” says one stalker, correctly. Some reference radiation maps. Some take care to bring their own water supply; others drink from the highly contaminated ponds or rivers inside the Zone, sometimes out of necessity: “We got lost and ran out of water. We had to collect morning dew from the greenery until we could find water.”

Others drink water in a misguided show of videotaped heroics. One infamous stalker, seemingly maligned by both stalkers and officials alike, is a Russian named Sergey Papov. Alexandry Naumov, a retired military police officer who now monitors the Zone, showed me a video of Papov drinking from the Pripyat River near the plant’s cooling pond, which is surely the most contaminated water in the Zone. “By doing this he is sending a message to everyone who’s watching that there is nothing dangerous about the Zone,” says Naumov with disgust.

Papov is now in prison for possession of drugs. When he was arrested, radioactive items that had been removed from the Zone were in his home, Naumov tells me.

V. and his young friend walk under a bridge near Rudnya-Veresnya village, under which a sandy-colored, sluicy river flows.

“We’ll collect some water from the river to drink,” says V.

His friend rinses out their plastic beer bottle, fills it with river water, and then hesitates.

“Come on now, drink the water. Then you’ll film me. I’ll drink some, too.” He drinks … then passes it to V. “This water is great,” says V., as he finishes the bottle. “Probably better than in Kiev.”

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone can be a place where adrenaline and headier interests and curiosities can meet.

“For stalkers, it is a unique place where you can find old production facilities and lost military machines,” says Sergiy Paskevych, an ecological expert and head of radiation safety in the Exclusion Zone. Indeed, many stalkers seek out these spots where Soviet cleanup machinery (“machinery cemeteries”) was piled or buried after the accident. These are among the most contaminated locations and are often unmarked and unmapped because the government did not keep records. Finding them is part of the “adventure.” GPS and dosimeters help. (Several sources report that the machinery dumps are dwindling in size: Scrap metal is a valuable thing in a broken economy, and the government is rumored to be selling it to China.)

Many stalkers swoon over a kind of natural setting they’ve never seen before. The mass exodus of humans after the accident has been a boon to many species, and the Zone has become an unlikely animal refuge. Scientists have discovered mutations in species, but to put it in crude terms, the upside of the absence of humans has far outweighed the downside of radiation for some creatures.

“Try to imagine: One hundred kilometers from Kiev, you can look at a wide range of predators, bird of prey, wild boar, roe deer, moose,” says Paskevych, explaining this appeal for the stalkers.

But the Zone’s wildness can also mean danger. One 27-year old told me a harrowing story of entering an abandoned cottage at night only to be attacked by several wild boar, which are notoriously vicious Another group spoke of chain-smoking to keep an angry mother moose at bay, and of the chilling mating sounds that echo through the black Chernobyl nights. “Autumn is the moose period of ‘marriage,’ and they scream at night. … It sounds like a cow, lion, and bear combined.”

It is officially forbidden to hunt or eat wild animals from the Exclusion Zone, which can be highly contaminated, but in a country facing economic and political crises, and living with endemic corruption, the laws are often ignored. Police generals, charged with enforcing the rules of the Zone, are said to shoot game from helicopters. Contaminated meat of poached animals, some say, ends up in nearby restaurants. The ubiquitous mushrooms and berries, notorious absorbers of radiation and beloved throughout Ukraine’s Polesia region, make it to the country’s spottily monitored markets.

The leaves on the birch trees that crowd the spaces between the Pripyat apartment buildings are turning orange and red. It is V.’s fifth night in the Zone, the second in a Pripyat apartment strewn with cheap high heels from the ’70s and decaying ceiling tiles. He has explored the kindergarten, tinkled piano keys in a music store, and picked his way through a destroyed gym; read dusty handwritten love letters from another era; crossed rivers, wondered over brilliant stars, and pilfered condensed milk. He has found the peace that the Zone delivers him.

“In S.T.A.L.K.E.R.,” one of the game inventors, Alexey Sytianov, says, “the most important thing is the mystical atmosphere. Being around abandoned, destroyed places while heading toward one big goal and true wish, the player starts to be in contact with something—something that is even hard to describe with words. It comes from the destroyed surroundings, and from what he is believing in.”

What do the stalkers believe in? An invisible enemy that might kill them at 50 years old rather than 70? No. Walking through their past on their own terms? Maybe. Responding to the energy and potential of their youth, despite the risk? It seems so. Clearly, stalking delivers them the present moment—the lawless wild greenery and pathless reality of the Zone—that makes them, if only for a short while, masters of their destinies.

As the sun starts to descend, he makes his way to the roof, where others—Belarusians, Russians, Ukrainians, a Latvian—come together to watch the sun set behind the hulking, cracked sarcophagus that covers Reactor No. 4. It may not be the Golden Sphere that will make all their wishes come true, but they drink in a happy moment, on a sparkling autumn day, having reached their goal. Budjmo!—a vodka shot goes down.

A voice yells from atop another building: “Slava Ukraini!”

Glory to Ukraine!