The largest photojournalism festival in the world, Visa Pour l’Image provides a sense of continuity and stability in difficult times.

Yunghi Kim’s first overseas assignment was in Somalia. She was 29 and had never been to Africa. A staff photographer at The Boston Globe, she was sent in 1992 to cover the famine that claimed the lives of over 200,000 people by that year.

She had barely arrived when she and a reporter were taken hostage by a warlord. They were rescued after 13 hours in captivity and a few days later, Kim was on a relief flight back to Somalia to complete her assignment.

“I was scared shitless,” she tells me in the beautiful Sainte Claire convent in Perpignan. An exhibition of her work in the region called “Africa, the Long Road Home: from Famine to Reconciliation, 1992-1996” is being presented as part of the Visa Pour l’Image festival this year. “I’m told that’s a good thing because if you’re not scared, there’s something wrong with you. But it’s something that I had to do. I wasn’t not going to complete the assignment.” Her coverage of the Somali famine was a runner-up for the Pulitzer Prize in 1992.

Violence against photojournalists isn’t new. And Visa Pour l’Image makes a point of it: past winners of the Ian Parry scholarship are exhibited in the Minimes convent, honoring the British photojournalist who was killed at 24 during the Romanian revolution. In the Hotel Pams, a retrospective of Chris Hondros, the photojournalist killed in April 2011 with Tim Hetherington, is one of the highlights of this year’s festival.

But this year, the risks that photojournalists take reporting stories around the world feel especially contentious. As I enter the large Palais des Congrès, which serves as somewhat of a base for the festival, the first thing I see is a stand on the left that reads “Homage à Camille Lepage.” The 26-year-old French photographer was killed on May 12th, 2014, during an ambush in the Central African Republic. She was working on a story about child workers in diamond mines.

Her last ever photos constitute her first, though posthumous, book. On sale for 10 euros, I’m informed proceeds will go to a fund that will be presented at Visa next year. Nearby, I visit an exhibition in homage to Anja Niedringhaus, the Associated Press photographer who was killed in Afghanistan in April 2014.

Thirty-three journalists are confirmed to have been killed doing their job in 2014. Of those, 17 were photographers. With the shocking executions of James Foley and Steven Sotloff broadcast worldwide, the dangers of being a journalist in the 21st century have never been clearer. The Committee to Protect Journalists says that the last two years have been the most dangerous for journalists on record, with 174 confirmed deaths since 2012.

The largest photojournalism festival in the world, Visa Pour l’Image provides a sense of continuity and stability in difficult times. With 26 exhibitions, evening screenings, as well as grants and prizes that amount to a total of around $200,000, it attracts around 230,000 visitors over two weeks. The shows are dotted around the quiet southern city of Perpignan, which a local tells me, comes alive twice a year – during Visa and the religious processions at Easter.

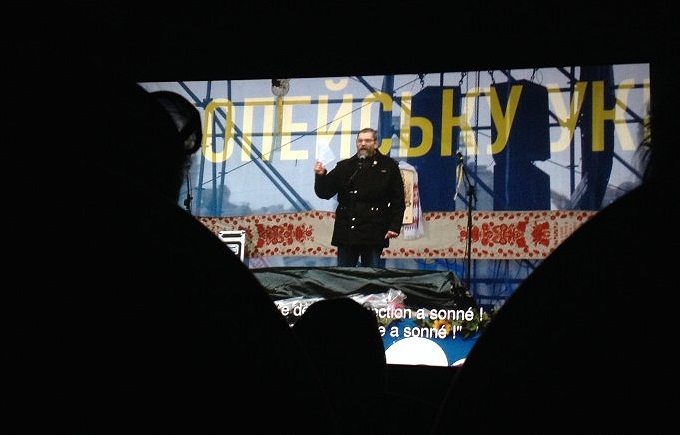

This year’s edition of the festival places a special importance on the religious conflict in the Central African Republic and the crisis in Ukraine. After a screening of “Maidan,” a sublime film by Sergei Loznitsa, photographers Guillaume Herbaut and Maxim Dondyuk discuss the challenges of reporting in Kiev. At least six journalists have been killed there covering the revolution since the beginning of the year.

But the festival isn’t just a solemn affair. In the narrow and winding pastel streets, strangers collide to let cars pass by. The mood is cheerful and the extreme friendliness of locals is infectious. Terraces are full and tapas are out (we’re a 30-minute drive from the Spanish border). At night, visitors climb onto the metal bleachers at Campo Santo to watch the evening shows, a sort of photographic meditation on the main events of the past year accompanied with music. Then, they party and schmooze at the Café de la Poste.

That’s where I meet Stefano Carini, editor in chief of Metrography, Iraq’s first photo agency. “Photographers choose to go wherever they want,” he says. “My approach to it is I will try to persuade them not to go until I’m convinced of their reasons, until I know that they will do it anyway. When that happens, I will give them full support.”

Jean-Francois Leroy, the festival’s founder, has lost many friends and colleagues, says Carini. This year’s edition of Visa Pour l’Image reminds us that photojournalism has always been dangerous work. And that somehow makes a very bad month for reporters seem a little easier to take.