Cengiz Yar photographs the refugee children that have taken shelter in Syria’s bordering countries.

A year after the news of a devastating chemical attack in Syria brought the conflict briefly back into the international spotlight, war continues to rage. The death toll is now approaching 200,000, and around 3 million Syrians have fled their country. But how do you report on Syria these days, when it has turned so deadly for journalists? At least 69 reporters have been killed there since the conflict began in 2011 and approximately 80 have been kidnapped. For documentary photographer Cengiz Yar, it has become impossible to go, as he did in 2012, into Aleppo with the Free Syrian Army. But he didn’t want to abandon the Syria story, so instead he spent time with the Syrian refugees that have taken shelter in bordering countries. In particular, he wanted to meet the kids who have been most affected by the crisis. In the space of two months, he photographed over 150 Syrian children in four different countries. He spoke to R&K near our Brooklyn offices during a recent visit to New York.

Roads & Kingdoms: What is the concept behind this project?

Cengiz Yar: It’s designed to put a face to the crisis in Syria. I think that a lot of the stories that are coming out of Syria and the refugee crisis overlook the individuals and are more focused on the big picture. It’s really easy to look at a number and forget that there are people behind it. There’s a real lack of connection especially between the American audience and Syrians. I wanted the American audience to care about what’s going on over there as much as I care about it. These kids have gone through really traumatic times, but that doesn’t mean they don’t need to be respected just like any other kid. It doesn’t mean they don’t have something fun to say or that they don’t love corn-on-the-cob or pizza… I just wanted to try to bring that home.

R&K: What does the project look like photographically?

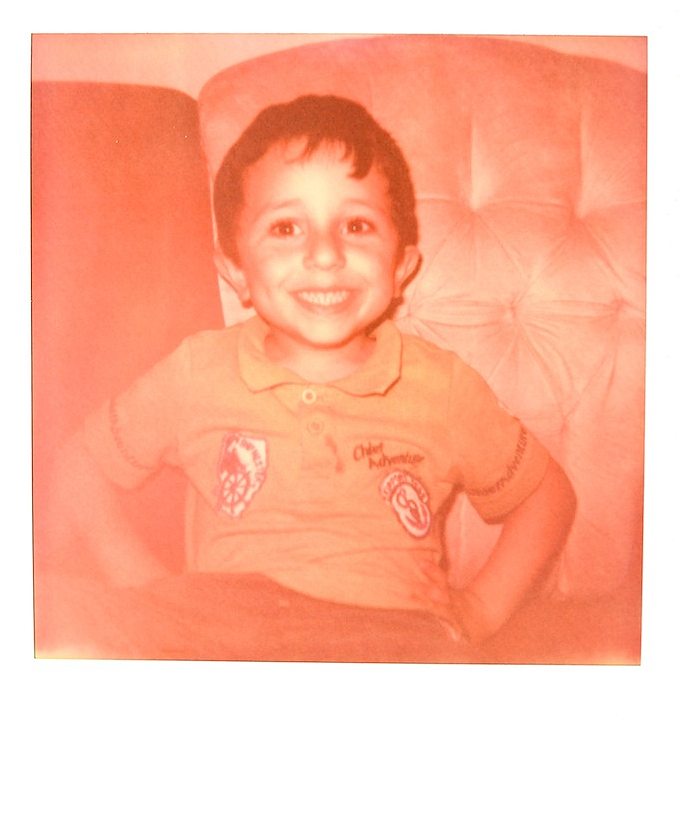

Yar: The idea was to have a portrait of kids I talked to and then get them to tell me a little bit about themselves. The Polaroid part of it was me trying to conceptualize some way to give back a photo. I love film and I love how Polaroid film is unique. It creates beautiful texture and color and I really wanted to share that with the kids and also record it, so I could share it with an audience. The kids’ reactions to getting these pictures back was just unbelievably beautiful and a lot of these pictures just turned out perfect. And being able to honestly tell a kid: “this is one of the best pictures I’ve ever taken” and see that smile was just so cool. The whole concept was to communicate the faces and the stories of these kids.

R&K: Which countries did you travel to?

Yar: The four countries that are the most affected by the Syrian refugee crisis right now are Turkey, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon – there are also large Syrian refugee populations in Sweden, Italy, Libya, Egypt, and a variety of other countries in the region. So the goal was to go to border towns all along the way. I started in Gaziantep and then went to Antakya, which is a southern Turkish town and to Kilis, a pretty infamous border-crossing site. Then I went to Diyarbakır in Eastern Turkey and I crossed into Kurdish-controlled Iraq. There, I did a lot of refugee camp work, so I stayed with an NGO called Rise. They’re an amazing organization doing excellent work for refugees and are now focusing their attention on refugees from the recent ISIS offensive in Iraq. I would go to the refugee camps every day, observe their work for a little bit and then go off on my own and hang out with the families. In Jordan, I wasn’t focusing on Zaatari, the biggest camp that’s very well-known, because I think a lot of the stories that are outside of it have been missed. So I went to refugee communities in Amman and in one of the border towns. Then I went to Beirut and to some of the Palestinian refugee camps that are now taking in Syrians, as well as makeshift camps in Bekaa Valley.

R&K: So you didn’t just focus on the refugees who lived in camps…

Yar: In Turkey I just did schools and refugees living in apartments in makeshift shelters. Iraq was all camps. Jordan was all apartments and then Lebanon was a mix of both – no official camps though just makeshift.

R&K: Is there one country that particularly stood out for its conditions or for its response to the refugees?

Yar: Each country is very, very different. I would say the best conditions for living as a refugee that I encountered were in Turkey. I’d say that refugees were treated the best by their neighbors and a lot of them had schools they could go to. Not every kid could afford to go, but there were a lot of Syrian schools in Turkey. Most of the families had food to eat. Relatively speaking, conditions were pretty good. In Iraq, the camps were well taken care of, they had food. They were terrible conditions for anybody to live in but they were safe and people had enough to eat. They were extremely bored though and there weren’t enough doctors in most of the camps and the schools were overwhelmed. But the Kurdish government, from what I saw and was told, is doing an excellent job taking care of the Syrian refugees. I don’t think I met anyone in Jordan who enjoyed living there. All the kids told me they hated it and they hated their neighbors and they were having fights at school… I’d say that across the board, Jordan was probably where there was the highest tension between refugees and local residents. Lebanon was the saddest, the most abject conditions of poverty that I saw Syrian refugees living in. A fourth of the population of Lebanon are Syrian refugees, they’re everywhere. They’re being taken advantage of by landlords, having their aid money and food stolen by locals, the conditions are really horrible. So Turkey I guess really stands out. They’ve even put in regulations so that if Syrians are being taken advantage of by Turkish business owners, they can report them.

R&K: What is unique about photographing children?

Yar: It’s hard. You have to be really careful about not hurting them or endangering them. You have to be really sensitive, specifically when dealing with kids that are in circumstances like these. It was something I knew before going into this, that I would have to work very carefully.

R&K: Some of them are actually quite young, did you feel like they really understood what was going on?

Yar: I specifically was looking for kids between five and 15. Under five I found was way too young to grasp the conditions they were living in or remember anything about Syria. But then there were six-year-old kids that would just blow me out of the water with all the stuff that they wanted to talk about. For example they would remember the garden behind their parents’ house or their next-door neighbor who they used to watch pigeons with. Just all these crazy things that would probably have been missed if someone didn’t sit down with a six-year-old because they thought they were too young. The tragedy that’s happened because of this war – all these kids’ lives have just been completely up-rooted. Some kids had been in camps for three years, basically since the conflict had started, so all they could remember was living in a camp.

R&K: Can you talk about one child that had a particular impact on you?

Yar: There are so many… This kid in Jordan named Hamza, he was this awesome little kid who was running around, going crazy in the house. I was talking to his family, I hadn’t even started interviewing him yet and out of nowhere in Arabic he said: “I swear to god we’re Syrian.” It was the weirdest, funniest thing. It made everyone in the room laugh, including me. He took my notebook and was drawing in it and then we played patty-cake games and he wanted to show me how he would pray every morning. He was just a fun, awesome kid. His dad was describing how he saw the emotional change in his children, specifically Hamza, from this depressed scared child who would hide in his room everyday because airplanes were bombing his town and he saw dead bodies in the street and his neighbor’s house got hit, to being this fun kid I had in front of me because he was now living in Jordan. His father expressed how important that last year in Jordan was for their family and how happy he is, although life in Jordan is really hard, that Hamza is semi-close to having the personality he had before.

R&K: How did parents react to your project and to you as a journalist?

Yar: In certain areas, people were pissed off that journalists were coming through and not doing anything. In southern Turkey it was very evident, just because that route has been frequented by journalists quite a bit. And then just disdain in Jordan because they’ve been there for so long, they’re sick of it. In Iraq it was completely different because the Kurdish region of Iraq has been pretty much ignored by the media until recently. So in that region they were very accepting and they wanted to tell their story. But I would say that after my explanations, people understood what I was doing and they were very receptive. I remember specifically one grandmother saying: “you’re treating our kids better than how we treat them!” At the start of the project I made sure that I was asking the Syrians I interacted with: “how do you feel about this? Should I even continue doing this?” And the reaction was constantly: “this is important, yes.”

R&K: What did you talk about with the kids?

Yar: I had a list of questions that I varied depending on the child but always trying to keep the questions light so it was always like, what’s your name? Are you going to school? How old are you? What’s your favorite subject? What’s your favorite sport? What’s your favorite sports team? Just real simple, basic questions.

R&K: Questions you could ask a kid anywhere, really…

Yar: Exactly. Except for “what do you miss most about Syria?” which was always the last questions that I asked, and only if I thought they might want to talk about it or remember. The question that I had the most problems with though was: “if you could say anything to everyone in the world, what would you say?” A lot of kids didn’t understand that concept. It got a lot of funny or inquisitive reactions. And then a lot of kids just said: “I would just say thank you” or “God bless you.”

The website for “Syria’s Children” will be up soon. In the meantime, you can follow the project on instagram.