A photographer documents the surprisingly successful refugee population of Idaho’s capital.

A few weeks ago a delegation of professionals, public officials and volunteers from Germany descended on Boise, the capital of Idaho. Their goal: to learn how the predominantly white city of 216,000 integrates refugees. In 2015, nearly 700 people were relocated to Boise from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Over 300 more resettled in the nearby town of Twin Falls, placing Idaho in the top five most welcoming states for refugees. And though that might not sound like much compared to the one million refugees who crossed into Germany last year (the US has a cap at 70,000 people per year), Idaho is among the states with the largest number of refugees relative to overall population. Photographer Angie Smith had been noticing the changing demographics of Boise on her yearly visits to her relatives. She started documenting the refugees’ stories shortly before the migrant crisis escalated in Europe. Now, she’s raising funds to turn her project “Stronger Shines the Light Inside” into an outdoor exhibition. She joined R&K from Boise.

Roads & Kingdoms: What is your impression of Boise as a city?

Angie Smith: Idaho is a beautiful state, it has the Rocky Mountains and lakes and rivers, and Boise is a really nice city with lots of trees and a river that runs through town. It has old craftsman houses everywhere and lots of families. Everything is very family-friendly. People are kind, they are really active in trying to make their community better, and it’s the perfect place to build a foundation for this project. If I start taking it to other resettlement cities, I won’t have the same support system there, but at least I will have figured out my routine and how to get great pictures and great interviews.

R&K: You have been visiting Boise your whole life. Is that always how you felt about it?

Smith: Yes, my family history goes back three generations in Boise but my dad moved to Oregon in his thirties and decided to raise a family in Eugene, so that’s where I was born and raised. I pretty much always felt this way about Boise, and in contrast to Eugene, the sense of community there is very strong. I started noticing refugees when I would visit my family there and I just thought: wow, what an amazing combination, how amazing is it that they’re ending up here, probably the last place on earth they ever expected that they would live? But it’s actually a place where people are extremely welcoming and friendly, except for the small contingency of very conservative, obnoxious people who have made a lot of noise protesting the refugee resettlements. There definitely is that here, but it’s a small population of very loud people. And then there are a lot of people who just don’t really know much, they’re kind of indifferent to all of that.

R&K: Can you explain what the resettlement program entails and who’s involved in it?

Smith: Boise has been a refugee resettlement city since 1975. It started with the governor who was in office at the time and he was responding to a national call to take on a bit of responsibility for resettling refugees. Boise was established as a resettlement city then, and it’s really changed throughout the decades. Back then they were accepting refugees from Bosnia and Vietnam, in the 90s and the 2000s it started to shift to the Congolese and now it’s a mix of a lot of different African and Middle Eastern countries, with a small percentage of Syrians.

When they find out they’re going to the US, they expect Los Angeles, New York, Las Vegas.

R&K: Has the opposition to the program existed since the 70s?

Smith: It’s definitely more recent than that. In the last year or so, since the terrorist attacks and since the refugee crisis in Europe has been in the news, I think that it’s become more widely known and recognized that refugees are resettling in Idaho. There have been a few pro-refugee demonstrations at the capitol where these people have shown up across the street, and so it’s been very contentious in the last year.

R&K: You’ve spent time with a number of people who arrived recently to Boise. What are their first impressions of the town?

Smith: A lot of people have told me that when they find out they’re going to the US, they expect Los Angeles, New York, Las Vegas… They expect skyscrapers and beautiful cars and big houses. When they get to Idaho, they’re just like: man there’s nothing going on here, where are the people in the streets? It’s so quiet, it’s kind of boring. But then they always ended up telling me that they loved Boise. The number one response that I got was that it’s peaceful and calm here. I haven’t interviewed anyone who said they didn’t like living in Idaho.

R&K: So through this program they get help finding a job and a home in Idaho?

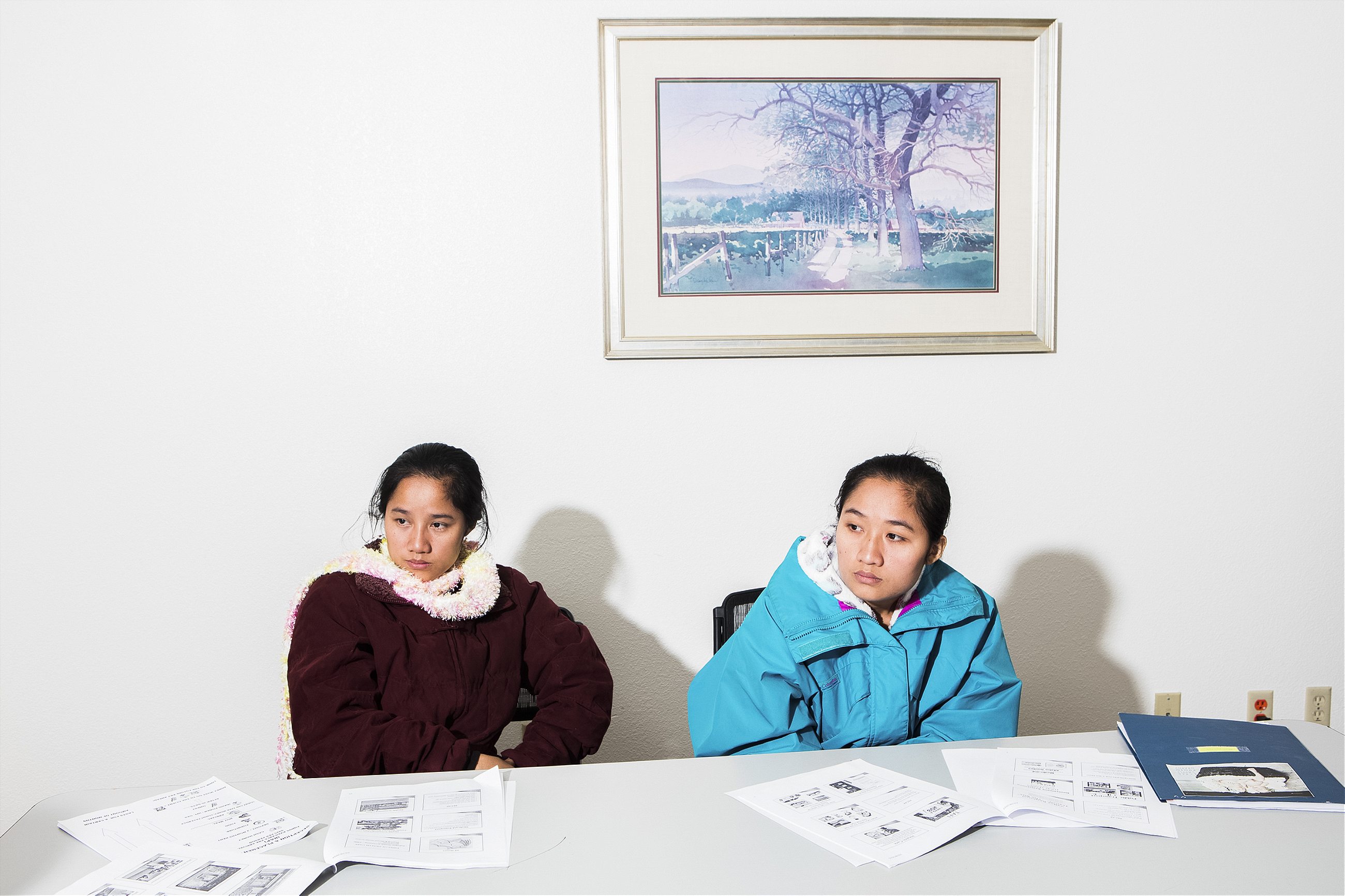

Smith: Once they get here, they are taken care of by one of the agencies—International Rescue Committee, the Agency for New Americans or World Relief. The support usually varies between three and nine months. They get intensive English classes, job training, and all of the agencies have a lot of workshops and resources. If you go to the IRC here in Boise on any given day, you’ll see lots of families sitting in the waiting room and meeting with their case workers. They have volunteers who help with the process of getting families settled when they first arrive.

R&K: Did you document that process too?

Smith: I have gone to the IRC and just hung out in the waiting room and photographed people there. I have gone with case workers to the airport for pick ups, and then gone with them when they take the family to the hotel room and photographed them on their first night in Idaho. The IRC stocks the refrigerator so I took pictures of the food items that are waiting for the families. Now that I have a couple months left to finish the exhibition, I want to be focusing more on that because there are just so many interesting moments and things that happen in the first week of someone’s life here.

R&K: Tell me about Rita Thara and the role that she had in shaping the project.

Smith: Rita was the first person that I was introduced to who was a refugee in Boise. She and I really clicked. We’re around the same age, we’re both creative people and I don’t know, we just got along really well. She loved having her picture taken, so it was great to start practicing on her and shooting her in different situations. She also has a fashion company here and she’s always sewing new outfits and needs new pictures. She introduced me to her neighbors and friends, and she goes to this church where most of the congregation is from the Congo. I offered to take family photos there. She was my introduction into the Congolese community, and then the agencies helped me get introduced to the other communities too.

R&K: The project really kicked off when you got a grant from the city of Boise. Can you explain what your dialogue with them was like?

Smith: I proposed to them that I would create an outdoor exhibition and that it would be in three locations around the city. By giving me the grant, they were accepting that plan, and they’ve been really supportive. I think they had no idea it was going to be this big, and now they’re starting to understand that it could even become a tourist draw, it could have an economic benefit for the town. Right now I’m trying to confirm the exact locations of the banners. It could be a really positive thing for whatever business is near, because a lot of people will be attracted to come and look. I think they’re really excited.

Boise is starting to become recognized for this work.

R&K: I was reading the local press coverage that you got. Idahoans seem quite proud of the project.

Smith: I think they are really proud. Boise has built a reputation on just being a great place for refugees. And many organizations and people in the community have started groups and non-profits to fill in the gaps because the agencies can only do so much, so there have been a lot of other programs that have sprouted up. I think Boise’s starting to become recognized for this work.

R&K: Do you think it can be used as an example for other places in the US and in the world?

Smith: Definitely. It’s probably one of the best examples of how to help. But Boise still has a way to go. There are still improvements to be made with further integrating the refugee community. It’s an example in terms of the community self-motivating and volunteers stepping forward. I think the people here are really wanting to do more, but because Boise has had such a lack of diversity for so long and a lot of people in Idaho have never left the state, I think many of them don’t know what to do. They don’t know how to interact with people from a completely different culture. The education factor is really important.

R&K: Was it important for you to work on this project now, as the presidential campaign touches on these issues and the refugee crisis escalates in Europe?

Smith: Yes. I actually started this before everything exploded, before the terrorist attacks in Paris. It was March 2015. I found out I got the grant in August, and the months after that were when things really started to heat up. I had enough time to get a good head start and a solid body of work established before everything started exploding. And then when things started getting really contentious in Boise, people were like: how does this affect your project and what you’re doing? Is it making it more difficult? And I was like: no, it’s just making it more important.

R&K: In a way, you’re showing a new face of Boise. How did your family and longterm residents react to seeing their town in such a different light?

Smith: I think they were surprised. When I find myself in conversations with native Boise folks, they say they have seen refugees walking in the street or waiting for the bus. They don’t know where they live, they don’t know what their lives are like, they don’t know anything about them beside just seeing them in passing. I photographed a couple of people next to the Boise river and the foothills, and people from here love seeing the beauty of Boise combined with the portraits. It will be interesting to get feedback from the residents who are just a bit more indifferent. I know there are a lot of people who don’t necessarily have negative views, but they just don’t really care. I’m curious to know if my pictures can touch these people.

R&K: Is that why you decided to create an outdoor exhibition rather than a gallery show?

Smith: Yes, exactly. I want it to be something that people can’t miss. They won’t have to go out of their way into a museum and pay five dollars to see it. I want it to impact people who didn’t think they even cared, and even if they stop and look at one picture and read one interview, they might walk away feeling like: god I had no idea that this is what some of these people have been through. Maybe it will strike curiosity and they will want to know more, and then that can hopefully change people’s perspectives.

[Top image: Sonia adjusts her head wrap in the front yard of her home in a suburb outside of Boise. Sonia is a former refugee from Togo. She has lived in Boise for 18 years and is now an American citizen. She has worked full time in several local Boise hospitals but recently realized her dream of opening her own hair-braiding business.]