Boat-dwellers have been living on Britain’s canals since the industrial revolution. Will their unique culture be able to survive Britain’s latest boom and bust cycles?

For many tourists, authors, and daydreamers, Oxford, England is a fairy-tale world of spires and towers, medieval gentility and lofty knowledge. But as with all heritage sites, its identity is a mythology. When you scrape it away by turning down the wrong street or stepping into the wrong building, you’re confronted with Costa coffee, fluorescent lighting, and ill chosen plastic office furniture: all the accretions of modern England that we strategically ignore in favour of quaint pubs and cobblestone mews.

Yet there’s one part of Oxford that seems to live apart from the rest of the city, and from the rest of the nation. It’s not ostentatious, and it doesn’t announce itself. Just beside a car park in the center of town, the Oxford Canal unceremoniously branches off from the River Thames. It meanders along the western edge of the city, often obscured by apartment complexes or leafy inclines. But not far from the headquarters of the Oxford University Press, the canal spills out into the Port Meadow, a flat expanse of open common ground spotted with grazing horses and meandering townsfolk. Here, along the edge of the canal, the region’s river people have set up their liveaboard boats, forming small, floating communities on the fringes of the city, and a world apart from the day to day life of most of their countrymen.

The Oxford Canal, stretching over 78 miles and 97 mooring sites from the Thames in the south to the Hawkesbury Junction near Coventry in the once industrial English midlands, is just one small part of a whole parallel British dimension. At least 3,000 miles of canals and rivers under the care of the UK’s Canal & River Trust crisscross the English and Welsh countryside. At least 34,000 licensed boats wend their way along these routes. Most of these are just land dwellers out for a temporary escape, but somewhere between 4,500 and 6,000 of the boats on the canals belong to permanent boat people, those 15,000 or so Britons who have chosen to live their lives entirely on the water, and by so doing separate themselves from much of what defines the economy and life of the average Brit.

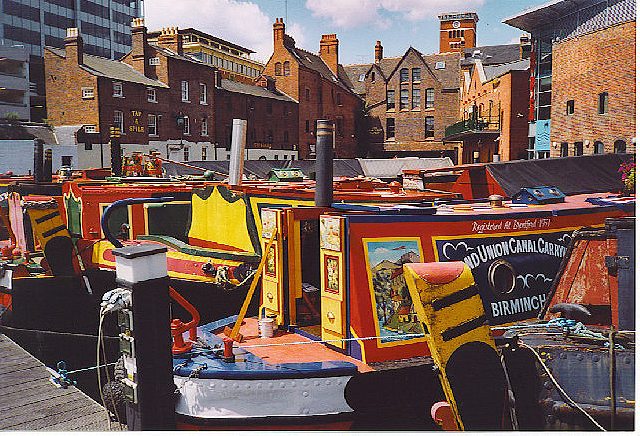

It’s easy to look at the rich, hand-painted narrowboats on the canals, up to 72 feet long and 7 feet wide, done up in rich, oily paints with names scrawled on their sides in a style ripped from the 19th century, and conjure up images of fantasy river folk à la the Gyptians of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, which drew on Oxford and its canal for inspiration. The boats and their denizens seem separate, noble, and idyllic. But that image whitewashes and exoticizes a diverse community.

Some boat people are here because that’s where they grew up. Some just love the water. And some are expressly seeking to abandon what they feel is a modern world gone awry. Some live on narrowboats, built to navigate industrial freight down the tight canals. Some live on so-called dumb boats, engineless blocks bobbing at a mooring. Some live on wide-beamed houseboats, those floating offshore flats. And some live as continuous cruisers, tooling around, never stopping for more than a couple of weeks in one place. What binds them as a community are the shared trials of near-autonomy—dragging your own sewage up an icy shore to a do-it-yourself disposal site, hauling your own water—and the same sense of greater or lesser dissociation from the mainland.

WILL THE CULTURE OF THE BOAT PEOPLE BE CROWDED OUT OR CONSUMED?

They also share a mutual threat to life on the canals. Over the last few years, as housing prices rise in British cities, the waterways have been flooded with more and more everyday folk who buy houseboats thinking it’ll be a cheaper way to live. Many will soon realize that the hidden costs of water life add up, or they will fail to integrate into the community, and eventually wash out. But in the meantime, many of them block up canals, bend the rules of the rivers, and bring more scrutiny to the waterways. The question becomes: will the culture of the boat people be crowded out or consumed?

The earliest populations of boat people in England probably date back to the early Industrial Revolution, when the canals were initially built to transport raw materials and manufactured goods to factories and ports. The Oxford Canal, amongst the oldest, was inaugurated in 1769, and then opened in stages from 1774 to 1790, carrying coal and limestone about the countryside on a path that followed the contours of the land. But the heyday of the canals was short-lived, as by the mid-19th century railways sprung up parallel to the canals, then began buying the waterways to control and snuff out their transit competition. According to Matthew Symonds, the South’s Boat Liaison Manager from the Canal & River Trust, freight continued to travel along the canals into the 1960s, until a particularly frigid Christmas season with no icebreakers allowed ice to block the canals so thoroughly that most good moved over to the roads and stayed there evermore.

As the industrial potential of the canals declined, though, people who had grown up around the water started to envision a new life for the canals. In the late 1930s, T.L.C. Rolt, a renowned industrial historian and biographer, purchased an old boat called the Cressy and retrofitted it to liveable standards, then began taking months-long cruises along the waterways. His 1944 book, Narrow Boat, helped to launch a movement from the 1950s to 1970s to save and revive the island’s canals as a leisure area, and as a protected home for permanent water residents.

Alan Wildman, the Chairman of the Residential Boat Owners Association, became a part of the boating community in the 1960s, during this revival. He sees a good degree of continuity in the type of people on the water and the nature of the community from his childhood onwards. “Society in this country is getting kind of aggressive financially,” he says. “People want everything now, they want everything quickly.

People like myself, we don’t like that much.” He and his fellow boaters have traditionally been those uncomfortable with the mainstream (alongside those who just like the water): people you’d cross the street to get away from, or marginalized communities. “There were a lot of gay people on the water” for a time, he recalls. “We are what we are,” says Wildman of the community’s approach to this ramshackle community of contented discontents. “We just enjoy what we do. We don’t care what you do, or if you have long hair or a bone through your nose. You’re a boat person, and we love you for it.”

Perhaps the presence of marginalized peoples living somewhat unorthodox lifestyles helped to spread an initially dim view of boat people across the country, especially in smaller towns with less river traffic. This ill repute has persisted in some districts even as boating has gentrified.

But, according to Wildman, “over the last five to ten years, there’s been an increase in boating, mainly because people see it as a cheap housing solution.” As of February 2014, housing prices in London had reached, on average, £175,000 ($300, 000) to £600,000 ($1,027,000), depending on the area. Panicked apartment and house hunters often look at boat prices—£10,000 ($17,100) for the cheapest immediately livable craft but £100,000 ($171,000) to £250,000 ($428,000) for something bigger and better equipped—and think they stand a better chance on the water than anywhere else. This may be why, as of the last boating surveys taken, at least half of residential boater households earned less than £30,000 ($51,000) per year: The lower wage bracket has decided that, while still pricey, they stand a better chance finding an affordable home on the water than on land.

LIFE ON THE WATER ISN’T ALWAYS THAT MUCH CHEAPER

The thing is, life on the water isn’t always that much cheaper, especially when one factors in the man-hours and attitude adjustment that the lifestyle requires. On the financial side, cautions Wildman, one must keep in mind the cost of a permanent mooring, few of which are available in overpriced and congested London (one of the main sites of the economic land-to-water flight). Then there’s council tax, parking if you have a car, assorted maintenance fees, and the price of water, electricity, and any other utility we usually take for granted.

The utilities do not come easily, either. Pumping in water supplies, offloading toilet waste, and finding and hooking up to electrical stations can be quite onerous tasks that few think of when looking into boat life. “Not everyone takes to it,” says Wildman, “especially if you’re iced in and you need to dump your toilet waste at a dump point a few miles away.”

Then there’s the claustrophobia of it all. The average 7 foot by 50 foot narrow boat amounts to 350 square feet of space for bedroom, kitchen, living area, toilet, and a cockpit, often shared by more than one person. According to Symonds, at least 75% of those on the waters are couples. And these rail-thin boats tend to be the more spacious models. “You wouldn’t get me back into a house, nor my wife,” says Wildman. “But if you didn’t get on, it’d lead to some friction.”

Despite these disincentives and boaters’ best efforts to ward them off, economically minded boaters have begun to clog up the canals at Bath and London. The 100 miles of canal and 42 miles of the Thames that run through London have at least a few thousand residents at the moment, although the numbers are hard to estimate as many canals and moorings bend the rules, fitting in more people than laws permit. At the worst, this can lead to slum boat conditions with 20 or more people sharing just a few shacks.

Some boaters, economically minded or not, also push the rules in an attempt to escape steep mooring charges, especially in places like London, by taking up continuous cruising licenses.

ONE OF THE LAST BASTIONS OF A TRULY DIFFERENT BRITAIN

This type of boater is obligated to move forward on a set course from place to place, staying in one location for no more than a few days. Most towns along canals have one to two day free moorings, and almost anywhere along a towpath, boats can tie up for at least 14 days. But rather than move directly forward, some cruisers just move back and forth along a canal from free mooring to free mooring, or move in tiny increments.

“We’re doing targeted work on new boaters who choose to be continuous cruisers,” says Symonds. He notes that the Acts of Parliament governing cruising specify that one must move forward in a continuous course from place to place, but do not specify what counts as a “place.” He and the Canal & River Trust plan to release a series of maps outlining places for reference in the coming months.

Many of those clogging up the canals right now will eventually wash out when they realize that life on the water is neither all cheeseboards and wine in the sun, nor that cheap and affordable. “I think there will be a natural plateau,” says Wildman, “especially when house prices go. It’ll self-regulate. But I don’t know when.”

A new era is coming, regardless. Perhaps it will come from new attitudes from canal authorities and local councils, inspired by the recent boating spike. But more likely the changes will come about because the boating population is aging. According to Symonds, at least two-thirds of boat people are aged 55 and over, and most young people only come onto the water as holidaymakers, rather than permanent residents. He and the Canal & River Trust are already looking into ways to make the canals more geriatric-friendly to accommodate the demographic shift, although it’s hard to install new infrastructure as most of the canals are heritage sites.

The absence of young Britons is either due to the expense of buying a suitable craft, or the result of a cultural shift away from the community and ideals Wildman describes. If it’s the former, then there’s a chance that youth will return after the economic crisis and integrate into the boat people’s world. If not, then these may be the dying days of this authentic remnant of industrial era history. It’s unlikely, and it wouldn’t happen fast, but it would be a shame, as the boat people and their happily marginal communities are one of the last bastions of a truly different Britain.

[Header image: Narrowboat on the Avon by David Merrett, used under CC BY 2.0]