A diary of fifteen days on a cargo ship.

DAY 1—April 26, 2013

The crew calls it a vessel. Not a boat, or a ship, or a freighter. A vessel. The most common topic of conversation among the sailors, when they bother to talk to one another, is how much they loathe being onboard the vessel—three-month stretches for the European officers, six-months at a time for the Filipino seamen—and the most common question for me, the MV Hanjin Geneva’s lone passenger, is “Why are you on this vessel?” said with raised eyebrows and an amused smile that suggests, You’re a fucking moron.

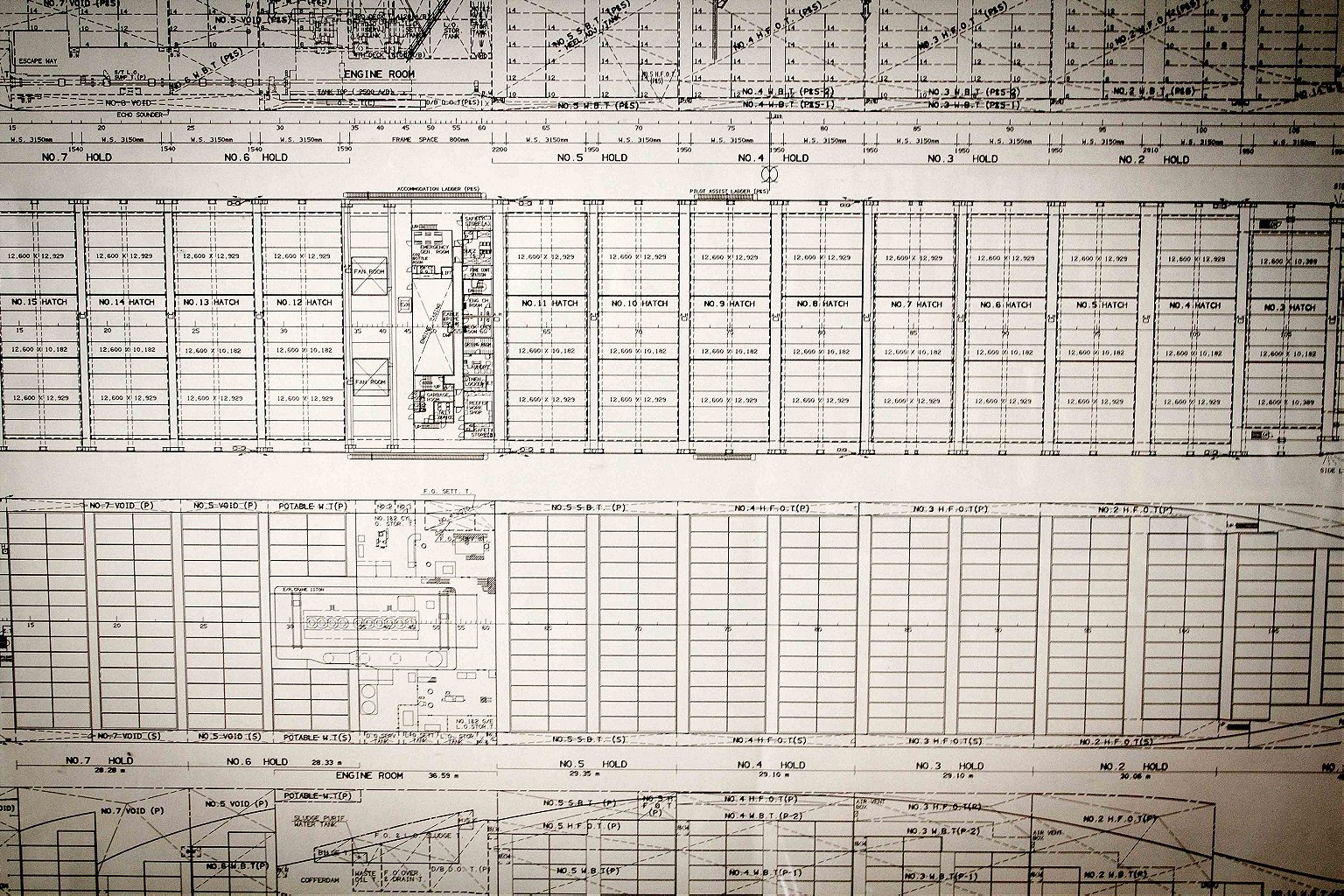

I board on a bright, warm morning in Pusan, Korea, along with a fresh batch of crewmembers, including the incoming captain, a gruff, chain-smoking German with hair like steel wool. I haul my luggage up the steep gangway as a massive crane piloted by a man in a suspended cockpit loads hundreds of containers. The Hanjin Geneva is humongous—912 feet long, weighing 65,918 tons, not including fuel and the 4,000-odd containers it can hold above and below deck.

Once the cargo has been loaded, we’ll set sail and spend fifteen long, ponderous days crossing the Pacific Ocean until we reach Seattle, where I’ll disembark.

Why am I doing this? The crew really wants to know. Really. Why? Why would you do this, when you could fly and save yourself the excruciating boredom of fifteen days at sea? The same journey would be approximately 350 hours faster, and several hundred dollars cheaper, if I took a plane. The sailors exhibit a kind of desperation when they ask this, as if my response might provide them with a clue about how to better endure the weary existence of life at sea.

I’ve always wanted to do it, I tell them. My dad, as a young man, had attempted to do so on his first trip to Asia. He and a friend went to the port in Vancouver and tried, unsuccessfully, to hitch a ride on a cargo ship. I remember thinking, Wow, that would be cool. So epic. Such a great start to a journey. (My trip was easier to procure than my dad’s; I bought a ticket through a UK-based travel agency called Sea Travel Ltd. that I found online. The voyage cost a hefty $2,200.)

In my case, it’s a journey that will end with me settling in the States after six years living in China. It’s a big move, and I’ve got two-plus weeks to think about it, with few distractions—no phone, no family, no friends or Facebook. What I do have is a stack of books and magazines and a brick-thick sleeve of pirated DVDs I bought in Beijing. I also have a big bottle of whiskey I picked up at a convenience store in Pusan, in case things get really desperate.

After embarking, the Hanjin Geneva’s Filipino steward, a slim man named June, shows me to my “Super Cargo” cabin. “Only the captain has a better cabin!” June says gleefully as he flings opens a door to reveal a room in shades of brown, featuring a double bed, a television and DVD player, a small couch, and my own bathroom. My cabin smells like shower mold and the tiny porthole windows offer a view of nothing but the backside of a container, but otherwise these are spacious digs.

I completely unpack my belongings—might as well make myself at home—and then take a walk around the multi-story tower, called a “superstructure,” which houses the living quarters, dining rooms, recreation rooms, gym and sauna, and navigation bridge.

After lunch, I wander up to the bridge and speak with Captain, who has cigarette-stained teeth and a uniform of a faded company t-shirt and dad jeans. He makes us cups of instant coffee and tells me about his background. He was in the East German Navy, and then the reunification Navy, where, despite crippling claustrophobia, he spent three years on a submarine, traveling as far as the Caribbean, where the sub, built for cold Baltic waters, was excruciatingly hot, so hot the computers sometimes malfunctioned.

Captain pats my back and says, “Back to work! So much to do.”

But there’s no work for me. I’m explicitly barred from working on the ship, in fact. Instead, I retire to my cabin for an afternoon nap. Job done.

We start moving around 9:30 p.m., 12 hours after boarding. I pour myself a glass of whiskey and go outside to the deck. I take a seat, light a cigarette, and blow smoke up at the biggest moon I’ve ever seen as we set off into the vast Pacific.

DAY 2

Wandering around the ship in the morning I run into a group of Filipinos. These are the guys who work below deck, paint the rusty bits, do maintenance, keep the engine firing, etc. Other than June, the steward, most of the Filipinos onboard speak terrible English, which is ironic because Filipinos dominate the cargo ship deckhand profession in part because they speak English, the language of the sea.

When I tell them I lived in China, they ask in garbled English if I married a pretty Chinese lady, and then they pantomime their hearts breaking when I tell them I didn’t.

This life? It’s not a life. On the sea like this for months. For what?

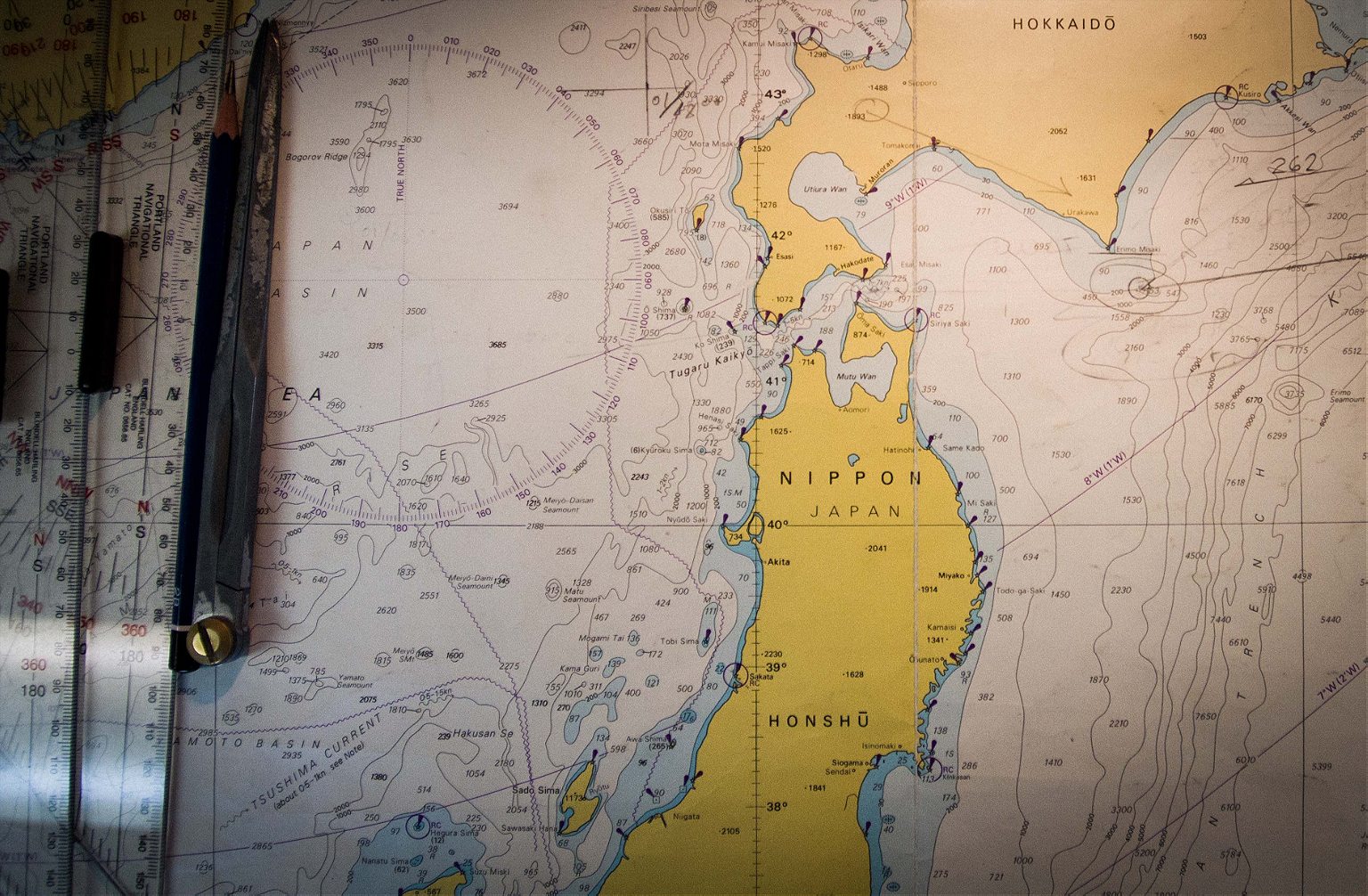

In late afternoon, I sit on the bridge with Claudiu, the 29-year-old Romanian First Mate. Once at sea very little is done on the bridge except staring at the ocean, smoking, and complaining. (Claudiu, I quickly learn, is a master of all three.) The ship’s cockpit, with its strange buttons and knobs, looks to be from a bygone era—straight out of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. Even though we have GPS, our location is updated hourly on paper maps. They are made by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office and feature places with very nautical sounding names: Musicians Seamounts, Chinook Trough, Shatsky Rise. There’s a notice taped to the wall that says if we’re attacked by pirates we must meet in the Ship’s Office on A Deck where a public address will be made.

I stare out at the rows of containers—“boxes,” in sailor parlance—and ask what we’re carrying. “I don’t know,” Claudiu says in his hard Romanian accent, “I don’t care.”

Claudiu has a shaved, balloon-shaped head and a wide smile. He is single and spends his off-months on the Black Sea, where he and his brother own a little shack and rent beach chairs and sell beer. He hates his seafaring job to the core but seems resigned in his hatred. “This life? It’s not a life. On the sea like this for months. For what?”

For the money, of course. It’s a good paycheck for many men from countries with limited opportunities. But times have changed for the world’s sailors. Today’s shipping industry is built on efficiency—goods are loaded and unloaded quickly, every dollar is accounted for, and the small crew works hard to make it all happen. Gone are the days when longshoremen painstakingly arranged every item into a ship’s hold by hand, or when sailors boozed away the long weeks at sea, counting down the days to run amok in Hong Kong or New York.

It’s dark in here now except for the radar screens and other illuminated buttons; the sea and sky is nothing but black. There’s nothing to see. Claudiu works two watches a day, from 4:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m., and then again from 4:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m., slouched in the captain’s chair, monitoring a radar for other ships that rarely appear. Sitting, thinking.

I try to point out the possible upsides of life on the ship, and he shoots them down one by one. The gym: he hurt his knee. The sauna: more than fifteen minutes is bad for your health. DVDs: “I’ve seen them all.” (He perks up when I tell him I’ll leave him my sleeve of DVDs when I disembark.) Books: “I don’t like books. I prefer watching movies. In my life I only read one book and this book I didn’t finish. It was Da Vinci Code. I read this book and the movie comes out so I stop.”

He laughs.

Much to my disbelief, Claudiu expresses zero interest in going ashore while in port. None of the crew does. If I were a sailor, I tell him, shore leave would be the highlight of the whole thing: The anticipation of leaving the boat, walking around town, drinking good coffee, getting absolutely shitfaced at night.

“What ever happened to ‘a girl in every port’?” I ask.

“What, should I have a tattoo of an anchor, too?” he jokes. “It’s not like this”—air quotes—“‘sailor’s life’ anymore. This is business. Maybe twenty years ago, sure, it was sailor’s life. Now it’s just I come here, do the work, take the money, go home. That’s why I tell you this is no life. It’s just business.”

DAY 3

Set clock ahead one hour.

I dedicate myself to twice-a-day workouts in the ship’s tiny gym in an attempt to get in terrific shape by the time I reach the U.S. The gym has free weights, a Nautilus machine, a stationary bike, a dysfunctional elliptical trainer, and a punching bag. Taped to the door is a piece of paper that reads, “Why get high when you can gym and fly?” (“To gym” means to workout in Filipino seaman lingo.) Above the bench is a faded 1990s magazine spread outlining Arnold Schwarzenegger’s training regimen.

After working out, I go up to the bridge and watch the ocean go by. Around noon we pass between the Japanese islands of Hokkaido and Honshu, with mountains and small towns on both sides. The sky is bright and a deep, saturated blue. We see a cruise ship and later a fishing boat getting hammered by the swell. “The real mariners are on that boat,” Claudiu tells me.

In the afternoon I take a full lap outside on the deck. I walk past the rows of containers. I walk up starboard, down port. There’s a basketball hoop at stern, but it’s too cold to play. Some Filipino deck hands are out here wearing yellow rain ponchos, painting and cleaning. I listen to the grinding, humming, stretching, and creaking of a working vessel. It sounds… powerful. It smells of grease and paint.

I’m disoriented all day because of the constant motion. I spill milk. I drop a used coffee filter on the floor, spilling black grounds in the dining room. June groans audibly when he sees the mess. In the gym, I accidently drop weights on the ground.

At one point, we receive a distress call about a fishing boat taking on water in the Indian Ocean. I ask Jarick, the ship’s hulking Polish Second Mate, who looks like a soft-souled European nightclub bouncer, why we got the call, since we’re an ocean or two away. He doesn’t know. He tells me that once, off the coast of Australia, his vessel received a distress call about a boat ferrying Indonesian refugees. They were twelve hours away and were instructed to go save the sinking boat, but arrived too late.

“Everybody dead,” he says.

DAY 4

Set clock ahead one hour.

June takes me on a tour of the kitchen, where the chef, who is also Filipino, is preparing a lunch of pea soup and sausage. “Call me Cookie,” the chef says with a beaming smile. “That’s a fitting name,” I say, and June leans in and whispers that all vessels have a chef called Cookie.

Cookie seems like a nice enough guy, but the food is already starting to get to me. (Of all the things the sailors complain about—and the list is long—food is right up there.) Cookie does his best preparing the “European” meals we eat in the officer’s dining room, but I can’t help but think he gets a perverse pleasure from his inconsistent cooking. I picture him peeking through the kitchen door and cackling maniacally as we stomach yet another plate of slimy cold cuts and fork into our mouths another salad made of wilted lettuce.

DAY 6

April 30, 2013: The day I live twice. We cross the international dateline and set our clocks back 24 hours. How do I take advantage of this rare opportunity? This chance at re-doing a day of my life? A chance to right wrongs, etc.? To live out my very own Groundhog Day?

I do nothing. I sleep till 10 a.m. I make coffee. I crawl back into bed and watch a DVD until noon, when I go down for fish soup and roast beef with green beans and potatoes. I workout (legs, shoulders, arms) and then go up to the bridge to figure out where we are on the maps. Later, I’ll eat, do laundry, read—anything to kill the hours until I can cross off another day from the calendar.

Today, I discover that ocean hangovers are worse than regular ones.

Early evening: I’m in the dim cargo ship weight room, alone. I ride the exercise bike and stare out the window at the ocean—dark, cobalt ocean in every direction. Divide the horizon into four and you have four quadrants of gray, 360 degrees of the restless North Pacific under a sky that is nothing but two shades of gray: medium and dark. I look at all this and think that there must be something profound to be found in such bleakness.

And then I burp and taste the gravy that topped the dry roast beef Cookie made for lunch.

DAY 7

Over lunch (vegetable soup, fried beef, mashed potatoes, cabbage), I chat with June about the only thing we’ve talked about since day one: basketball. In the States, the playoffs are in full swing. The problem is, we don’t know what’s happening, so our conversations are based on information that is days old. Basically we just repeat teams whose chances we like this year and list the players we know on each of those teams. We’ve had the following conversation three times:

June: Ahhh, but the Knicks… (raises eyebrows). When Melo gets in a rhythm… (makes shooting motion).

Me: Yeah, but you can’t rely on one guy.

Those exact words for three days.

Captain calls me to the bridge after lunch; he needs some info for U.S. customs. He complains about how aggressive and intimidating the agents are—they board the ship and do face checks and sometimes employ drug-sniffing dogs. “They treat us like we’re terrorists!” he says. “But without us, the U.S. no longer functions.”

I ask if we have a list of what we are carrying and he says no, it’s all on electronic files the shipping company provides to customs. The only thing we know is what’s in the Dangerous Goods containers. I look at the manifest and it turns out we’re carrying fireworks made in China.

“For, what you call it, Fourth July,” Jarick observes.

I find it very amusing that we’re carrying fireworks from China. All this—the endless days, the slow trudge across the North Pacific, the boredom—so that Americans can alight the sky on their country’s birthday.

(Later, in New York, a friend looks up the Hanjin Geneva’s full manifest for me. Among other things, the containers held: sleeping bags; bicycles; “assorted soya snacks” from Australia; Halloween accessories; car parts; frozen tilapia fillets; Samsung washing machines; men’s pants; women’s bras; soft drinks; and hot dipped galvanized steel.)

DAY 8

Set clock ahead one hour.

Breakfast: raisin bread

Lunch: soup, meatloaf, vegetables

Dinner: pork chop, veggies, ice cream

In the afternoon I walk to the ship’s front section—the oddly named “fo’c’sle”—dangle my legs through the railings, and sit. Crewmembers rarely come up here, and containers obstruct the view from the bridge. I’m completely alone—if for some unlucky reason I fell into the water, no one would ever know what became of me. I’m far enough from the rumbling engine that the only sound I hear is the bow parting the water below. Wind whips my face and the cold and quiet makes it feel like riding a chairlift in the mountains. All around me is ocean the color of ripe plum. The ship rises and falls, gliding through the water, this massive thing, bringing fireworks to America.

DAY 9

At night, after eight days of sobriety, I drink half a bottle of whiskey and chain-smoke cigarettes while reading Patti Smith’s Just Kids until late. Just for something to do.

DAY 10

Today, I discover that ocean hangovers are worse than regular ones.

DAY 11

It’s all about finding ways to kill time. Taking a little longer in the shower. Spending more time brushing your teeth. Flossing. Cutting an apple into slices instead of eating it whole. Looking forward to small things that mark the days. Coffee. Workouts. Sauna. Reading. A late night snack.

Your room becomes both a sanctuary and a prison. Despite having miles and miles of ocean in every direction, your world shrinks to the size of the computer screen on which you watch your nightly DVD.

Because of the motion and the almost nightly time zone changes, deep sleep is next to impossible. Your mind starts acting a little batty after a few days. It goes to dark places and gets fixated on strange, random thoughts, like this one, which I record in my journal: If I were to name a chewing gum flavor based on the taste you get on your tongue when you brush your teeth after drinking coffee, I would call it EspressoMint™.

DAY 12

Land! LAND!

We’ve almost reached Canada, where I was born and grew up. Tonight we’ll port in Prince Rupert, a small town in British Columbia not far from Alaska, and tomorrow I’ll be able to get off the ship for a few hours. Around us are islands, beautiful islands, some with trees and snow-capped mountains, all leading the way to the coast of B.C., which I can see on the horizon through binoculars on the bridge.

Today is gorgeous, not a cloud in the sky, crisp and cool and bright. Everybody is in good spirits, even the ever-gloomy Claudiu. He doesn’t plan on getting off, but like the rest of the crew he’s happy for one reason: Internet. For a few precious hours, the sailors will be able to Skype with their families, check emails, and get the latest sport scores.

Captain says he might disembark to get groceries. He’s craving Doritos.

DAY 14

My last full day onboard the Hanjin Geneva. I take a final walk on deck. As we sail not far from the coast of Vancouver Island, I see a pod of about a dozen orcas, one of which jumps out of the water, right up to the middle of its torso, and then plops back into the sea.

DAY 15

I learn many things from my 15 days at sea. I learn it takes great stoicism to be a sailor. I learn that there’s a lot of garbage floating in the ocean, even in the middle of nowhere. I learn that sketchiest dish in Cookie’s repertoire is oxtail and gravy.

Mostly, I learn that the seafaring life is not for me. I’m ready to get off. I’ve had too much time to ponder, too much time to stare at the ocean. Claudiu and I have run out of conversation topics and my joints hurt from spending too much time in the gym. I need a beer.

Thankfully, when I get out of bed this morning we’ve already arrived in Seattle. It will still be several hours before I’m allowed to disembark, so I take my time packing my things, snap a few more photos, and say goodbye to the crew. Captain invites me back for another trip. June says to email him if I ever go to the Philippines. I give Claudiu my pirated DVDs and tell him that if he ever passes through New York he should get off the ship and come say hi. He laughs and says he probably won’t.

The U.S. customs agents board and I tell a mustachioed officer why I’m on the ship and what my purpose is in the States. I’m somewhat nervous about how this is going to go down. But instead of grilling me, he chuckles and says that crossing the ocean on a cargo ship sounds like a “cool idea.” He flips through my passport, stamps it, and says, “Welcome to Seattle. Have fun.”

I haul my luggage down the gangway into a misty Northwest Pacific morning—another immigrant to America, arriving, like millions before me, after a long journey across the ocean.