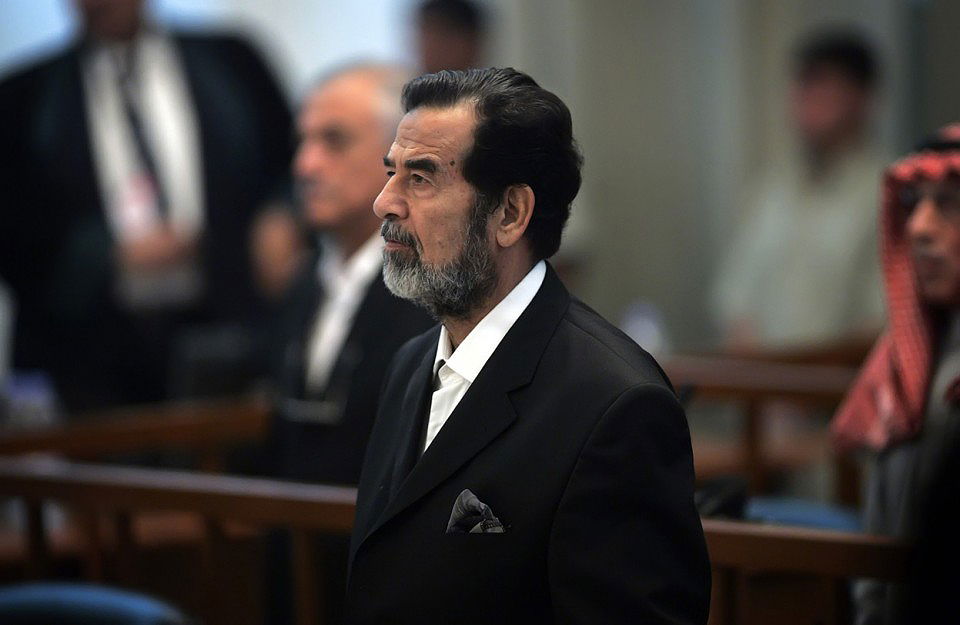

Ten years ago, Saddam Hussein went on trial for crimes against humanity. Meet the Kurd who outfitted him.

ISTANBUL, Turkey—

On July 1, 2004, former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s trial for crimes against humanity began. The deposed dictator, who was pulled from a spider hole a year earlier with a stash of Bounty candy bars and of 7 Up, was forced to face his accusers. Asked to state his name, Saddam fired back, “You’re an Iraqi. You know who I am.” In rambling speeches to the court, he took potshots at everyone from President George W. Bush to the Kuwaitis. The trial ended with Saddam’s execution two years later.

Saddam’s suit was made by a man who belonged to the very ethnic group the dictator had tried to annihilate.

For some, the trial brought closure to a long nightmare. For others, it helped legitimize the post-Saddam state. But for Recep Cesur, who followed the trial closely from Istanbul, it was something entirely different—a commercial for his unique line of menswear.

“I watched the trial from the first day,” Cesur says. “I wanted to see how he looked in the suit.” Despite the intervening years, Cesur, who sports a gray beard, can rattle off Saddam’s measurements: “His shoes was 11.6, his trousers 54, and his jacket 56.”

Astonishingly, Saddam’s suit was made by a man who belonged to the very ethnic group the dictator had tried to annihilate. Recep Cesur is a Kurd. During Saddam’s Anfal campaign in 1980s, 200,000 Kurds were killed and 4,500 communities razed. At one point, in a move that foreshadowed the tactics of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Saddam used chemical weapons against his own people. “Saddam’s politics were evil, but he was a good customer to me,” says Cesur, a proud Kurd who holds a deep admiration for late Iraqi Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani, who fought against Iraq’s Baathist state and died in exile in 1979.

While still in power, Saddam’s entourage bought 220 suits from Cesur’s Baghdad outlet, 80 of which were worn by the mustachioed strongman himself. Before the trial, one of Cesur’s employees in Baghdad prepared another set of suits for Saddam specifically for his historic court appearance.

In his youth, Cesur, who comes from the southeastern Turkish city of Diyarbakir, the largest Kurdish city in the world, taught himself men’s tailoring as he earned a living shining shoes. In the evening, he and his brothers would discuss plans for a future business. By the early 1990s, Cesur had saved enough money to buy an ailing tailor shop. Realizing many cities in the Middle East lacked quality menswear and custom tailoring, he opened a shop in Baghdad in the 1990s.

Today, Cesur’s suits are exported to three continents and his customers have grown to include statesmen and rebels. His list of clients includes former Pakistani President Perez Musharraf; Afghan President Hamid Karzai; and Ramush Haradinaj, the former Kosovo Liberation Army leader who was twice acquitted of war crimes charges. He exports 60,000 suits and 250,000 shirts a year from Turkey to clients around the world.

Over a glass of Iraqi tea, Cesur admits Saddam’s patronage has helped Iraq remain his largest market, followed by Belgium. He also believes his business has a tremendous potential for growth in Africa. He points out that, like Baghdad in the 1990s, many cities in Africa lack high quality suits and tailoring. Recently, Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, the president of Mauritania and current African Union chairman, purchased one of Cesur’s suits. In late March, Cesur took a trip to Ghana, which has a strong tailoring tradition, looking for business opportunities. He travels four months of the year. “I go through a single passport in one year,” he says with a smile.

Cesur’s most prized client was the late Nelson Mandela, who purchased a jacket and trousers from his label in 2000. “There has been no politician even close to Mandela in his importance and skill as a leader, not even Mustafa Barzani,” he says, referring to the Iraqi Kurdish leader.

When asked to name people he’d like to have as clients, he glances at the world map: “Nicholas Sarkozy is a fashionable guy. The prime minister of Denmark, what is her name? Helle Thorning-Schmidt? It would be great to tailor a suit for her. It would be an interesting challenge to tailor for a political leader who is a woman. Women can look great in suits as well.”

He’s stopped counting his appearance in local media, but claims to have been interviewed by everyone from Al Jazeera to Le Figaro. He reaches into his desk and flips through a German language guidebook to Istanbul that recommends visiting his shop.

IN THE WAKE OF SADDAM’S TRIAL, CESUR TRIPLED HIS SALES IN IRAQ

His shop is bustling. In the course of an hour an Uighur hospital manager stops in for a chat; a family of Kazakhs browses the aisles; a Cameroonian businessmen picks out 10 suit and tie combinations and begins to haggle over the price with Nicholas, a Moldovan salesmen. Cesur is comfortable conducting business in Turkish, Kurdish, Persian, and Arabic—a benefit of both his international travels and growing up in Diyarbakir, once an important hub on the Silk Road.

Cesur’s four brothers have played important roles in the growing empire. In addition to a small staff in Istanbul focused on tailoring and sales, the family business maintains a store and factory in Diyarbakir. In all, Cesur employs 350 full-time employees. Before the end of the decade, he hopes to return to Diyarbakir. “We Kurds should help each other economically and I have skills and business experience; I can give back to the community I came from.”

In the wake of Saddam’s trial, Cesur tripled his sales in Iraq. Prominent Iraqi leaders now visit his shop. Tariq al-Hashimi, who served as Iraqi vice president from 2006 to 2012 has taken up residence in Turkey and is a frequent client. A photo of Hashimi visiting the Istanbul shop sits on the wall in Cesur’s small office. Hoshyar Zebari, the Iraqi foreign minister, himself an Iraqi Kurd, also shops at Cesur’s.

He keeps information on all his political clients in a special record book. The first page contains Saddam Hussein’s measurements, but Cesur notes that he has to keep adding pages for new Iraqi businessmen and politicians eager to buy his trademark dark suits. Regimes may change, but style remains the same.