From ponytailed girls teams to beer leagues to the vaunted junior ranks, hockey is in Ontario’s blood.

The minivans and SUVs begin arriving at the Windsor Family Credit Union Centre in the dimming hours of a brisk afternoon, long before the puck drops for the Windsor Spitfires game at 7 p.m. The Spitfires, or “Spits” in local vernacular, are part of Canada’s vaunted junior hockey system, the lifeblood of a nation that spawned the winter pastime.

It’s certainly not the National Hockey League. Halfway across Ontario, in Toronto, fans regularly chuck $200 Maple Leafs jerseys onto the ice in a show of disgust against a team that earns tens of millions of dollars in ticket and jersey sales but shows little for it in the standings. According to ESPN The Magazine, the Leafs are the worst sports franchise in North America in terms of the value it offers fans. Ouch.

But junior hockey holds a special place in the hearts of Ontario hockey fans. Unlike multimillionaire NHL players, the teenagers who comprise the junior hockey ranks embed themselves in their teams’ communities. They often live with local host families who get a thrill from housing prospects for the big time. The whole set up brings people closer to the sport that defines their nation even more than mounted police or maple syrup.

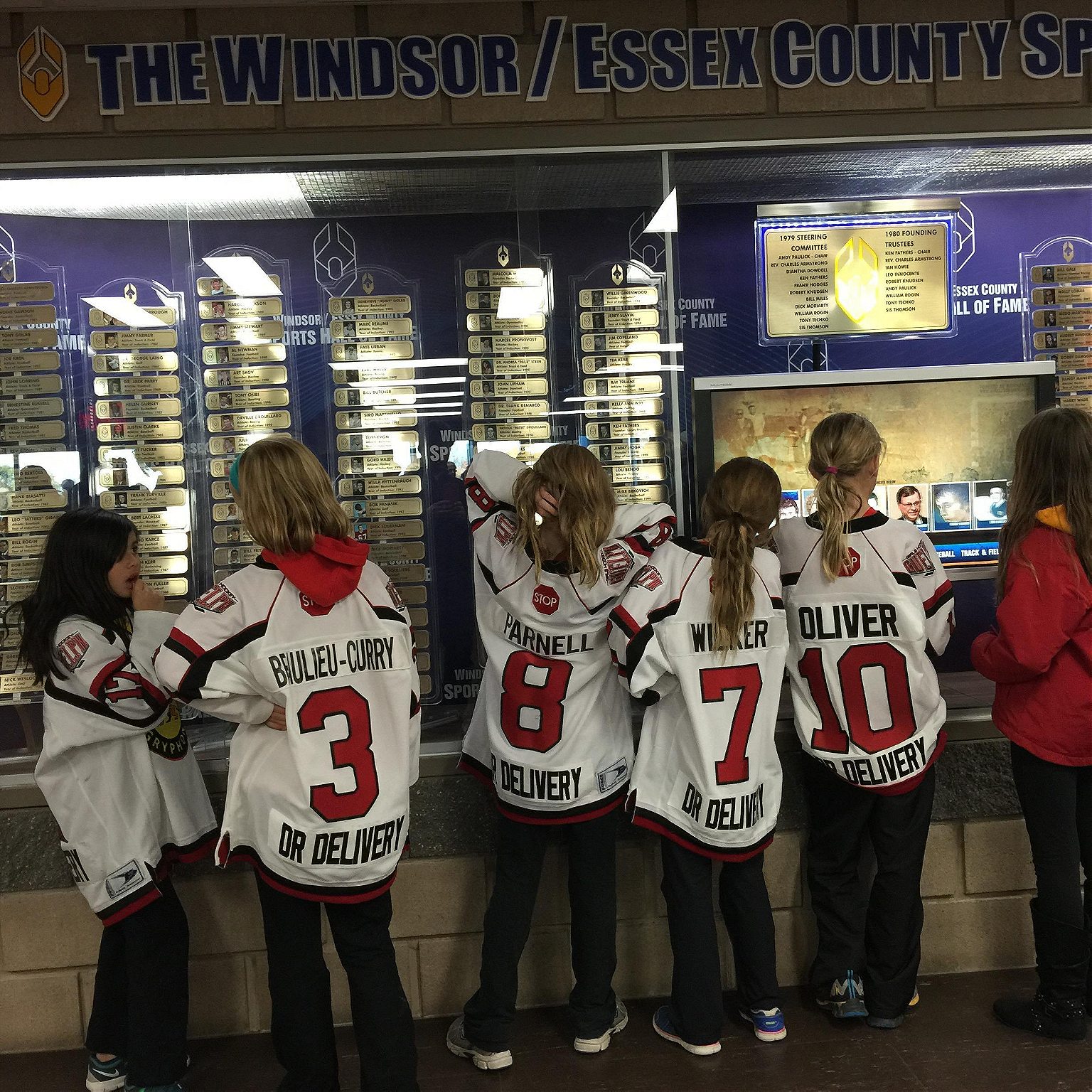

But in places like the WFCU Centre in Windsor, just over the Ambassador Bridge from Detroit, hockey’s grassroots go even deeper. Because all that traffic lining up outside isn’t for the Spitfires game. Out of the vans and trucks hop kids, some as young as five, lugging equipment bags bigger than they are. Soon, the arena’s lobby is teeming with chattering teens, tweens, and tykes, all waiting their turn to play in a weekend tournament.

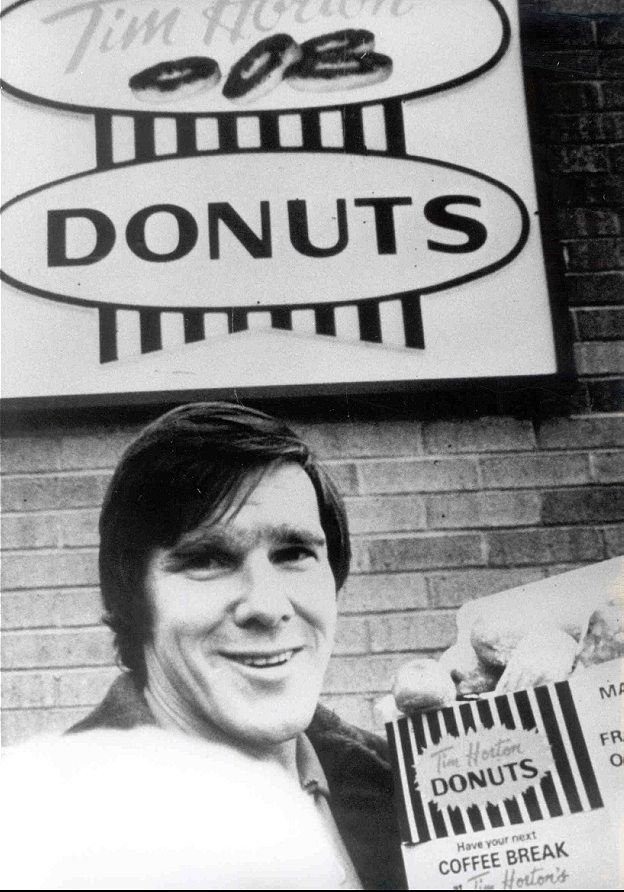

The parents, meanwhile, follow their children in a time-honored tradition shared among all hockey moms and dads. They stand in line at the Tim Horton’s cafe adjacent to the lobby. The coffee and donut chain is as ubiquitous in Canada as hockey, and the two often go together. It makes perfect sense that the namesake of the business was himself a professional hockey player before he started hocking donuts.

In many ways, this scene is what Ontario is all about, even though the origins of ice hockey stretch further east to Nova Scotia, where a group of college students adapted a field game from Ireland called hurling to the ice. The sport pushed west from there. The first known organized game on a rink occurred in 1875, at Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal.

Parents spend an average of $740 to suit up their kids

Today, however, Ontario boasts more youth hockey players than any other province in Canada. It produced Wayne Gretzky, the greatest hockey player of all time, who was born in Brantford and played junior hockey in Sault St. Marie. Ontario is where the most current Canadian-born players in the NHL call home. According to QuantHockey.com, 164 of the current 393 Canadian players in the NHL are from Ontario.

It’s an interesting time for Canada’s national pastime, particularly in Ontario. The International Ice Hockey Federation’s annual participation survey showed a decline in 2013, spurring newspaper columns about how rising expenses are driving out kids from middle-class families. Those equipment bags are huge for a reason. The CBC reported last September that between the skates, helmet, gloves, pads, and stick, parents spend an average of $740 to suit up their kids.

And that’s just equipment. Karl Subban, a father of three sons who were drafted into the NHL, told the Globe and Mail in October that one year he and his wife spent $15,000 to register all three in a minor hockey league in Toronto. No wonder more parents are shunning their Canadian birthright and registering their kids in expensive alternatives like soccer or basketball.

And yet the IIHF’s 2014 survey showed participation rates in Canada were up again, and the scene at the WFCU Centre seems to confirm it. When youth tournaments come to town, the lobby looks and feels like one big party. Kids group together and talk about whatever kids talk about these days, unburdened by any pressure of the game they’re about to play. It’s the parents who bear watching. They huddle together clutching paper coffee cups, talking about the commute and the weather. Then they start eyeing the clock as the caffeine takes hold and their kids’ games draw near.

They migrate to the bleachers opposite the team benches. Many stand against the glass, shouting encouragement and muttering comments about the refereeing to anyone standing within earshot. Toward the end of the game, they jostle for position with players getting ready for the next game.

The cycle repeats itself again and again until around the dinner hour, when angular teenage boys dressed in coats and ties arrive in groups of one and two. They weave their way through the lobby crowd to the stairs leading down to the Spitfires dressing room. A set of double doors near the Tim Horton’s swing open. A line forms. A man in a Spitfires polo starts scanning tickets.

The crowd for the Spitfires game is different. The youth hockey contingent has been at the arena all day. The coffee buzz is long gone. The adrenaline is spent. They just want to go home. The incoming fans—men, women, and children all decked out Spits jerseys, sweatshirts, and jackets—are fresh with excitement. They stream into the arena in the final hour before the puck drops.

This year’s Windsor team isn’t as strong as in seasons past. It doesn’t matter. The hype is palpable. The crowd builds and a square-jawed broadcaster mugs for the camera on the concourse during his pre-game show. About 5,000 people eventually pack into the concourse of the main arena for the Spits game, but it feels more like a neighborhood block party. Everyone is eating something from the concession stand, saying hello to familiar passersby between bites.

Spectators file into the rink to pulsating techno beats. Both teams have taken the ice for their pre-game warm ups. The routine is a wonder. Amid all the roar of music and fans, the players swoop in choreographed circles like birds of prey, flicking pucks with machine-gun precision at the net, forming lines at the boards and going through the whole thing again. The horn sounds. Fans settle into their seats. The game against the Mississauga Steelheads, and eventual 5-4 win for the home team, finally gets underway.

This happens everywhere in Ontario. The Ontario Hockey League has 20 teams, in towns as far north as Sudbury and as far east as Kingston. Most teams play in single-rink arenas where ice time is divvied up between local youth teams and the junior league squad. But two other teams play in multi-rink hockey hubs like the WFCU Centre.

The grand dame of the trio is about 180 miles northeast of Windsor in Kitchener, where Memorial Auditorium has been a monument to the sport since it was built in 1951. The solidly built main building looks as if it will stand another thousand years. The city tacked on two more rinks in 1986, and those host beer- and youth-league teams while the main rink and its 5,800 standing-room-only capacity is reserved for the Rangers.

In the western Toronto suburb of Mississauga, the Hershey Centre hosts not only the Steelheads, but also every other team in all of the major Mississauga/Toronto leagues. The place is a hive of hockey activity morning, noon, and night.

As in Windsor, the parking lot fills hours before the junior league team plays. The lobby is packed with kids and their huge equipment bags. Skates are laced, coffee is sipped, whistles blow. This is the essence of Ontario.