A road trip to southern Egypt with the exhausted optimists who are powering Hamdeen Sabahi’s presidential campaign.

Magdy is still groggy an hour after Mostafa shook him awake at 5:30am. But he and Mostafa need to make certain they have a place on the campaign bus heading south from Cairo to Sohag, the last campaign stop for left-wing presidential candidate Hamdeen Sabahi ahead of Egypt’s vote on May 26-27. Sohag is one of the poorest provinces in the Sa’id, Egypt’s south, a region that toppled Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi dominated in 2012.

Magdy, a fresh-faced university student with slicked back hair, is one of the army of youth volunteers that have taken to Egypt’s streets to campaign for Sabahi—the sole challenger to the state-groomed, ex-army chief Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, who led the 2013 coup against Morsi.

“How do you smoke this shit?” he grouses, struggling to inhale the Cleopatra cigarette. Mostafa—a paunchy, bespectacled techie—shrugs. He’s busy trying to decide whether to stock up on posters or not. The banners and flyers seem more important. He grabs a few for good measure and by 9am, he and Magdy, along with two other campaigners, Wael and Mohaymen, are speeding down the desert road in a minibus crammed with campaign material.

Just one of those Sisi billboards costs more than twice what you saw in our campaign office.

Before reaching the desert road, Mostafa pointed to a group of three large campaign billboards, a rather smug-looking Sisi peering out.

A look of stoic resignation flashed across his face. “Just one of those billboards costs more than twice what you saw in our campaign office.”

The outcome of the race has been all but decided in favour of the former field marshal, who has the machinery of the state backing him as well as the deep pockets of businessmen who control much of the private media.

Egypt’s media has frequently cited the results of one Egyptian pollster, Baseera, placing Sisi in a commanding lead. Their most recent survey on voting intentions shows support for Sisi at 76 percent, while Sabahi straggles behind with 2 percent. But the Egyptian polling centre was well wide of the mark in 2012. Indeed, a recent survey by the Pew Research Center, an American pollster, indicates that Egypt’s media has overemphasised Sisi’s popularity, pegging his approval rating at a less-overwhelming 54 percent.

These findings are telling of an ever grimmer public mood—a nation increasingly divided, but a Sisi victory, nevertheless, remains a foregone conclusion. This will be the result of months of state and private media propaganda calling for a strongman to save Egypt from all manner of internal and external plots. That and the recently doubled campaign spending limit, which heavily benefits the military brass and conservative business elite, who are happy to foot the bill.

But Sabahi, a seasoned opposition figure, couldn’t accept a single-horse race. Other opposition candidates had resigned themselves to that possibility when they withdrew in protest of a controversial electoral decree. But Sabahi believes electoral battles are part of the revolutionary struggle. He has battled before, surprising observers in the 2012 presidential elections when he placed third. And again, Sabahi—his thick crop of silver hair combed back and that charismatic smile at the ready—has entered into the fray.

He’s not alone. An army of passionate youth volunteers have taken up his cause. For them too, it is unfathomable that Sisi should run unopposed. They’ve been reared on the political ideals of Egypt’s 18-day uprising and the three years of revolutionary upheaval that followed. These ideals, they believe, must be given an electoral platform—a voice.

The four campaigners—all in their early twenties and full of grit and resolve—are prepared to fight for this voice, no matter how heavily the odds are stacked against them.

“We can only work to win, but if we don’t [win], at least we’ll know how loud our voice is,” Mostafa tells me. They will have built, even in defeat, a base and a strong opposition for future mobilisation.

He knows the media, the state and Mubarak’s rich cronies are behind Sisi. Sisi’s campaigners look more like thugs than anything, he says. But this doesn’t anger him.

“My anger and my grief are for those who died. The martyrs—some friends, some family, some neighbours and many others—who are still without justice. We can’t give up on their rights,” he says flatly.

“If Sisi is elected, we know he won’t do anything. It’ll go back to the way it was.”

Within an hour they are all conked out, awkwardly lodged amongst the reams of flyers. Magdy is sprawled diagonally across the front passenger seat, to Mostafa’s chagrin. They are the double act in this motley crew—Mostafa the long-suffering big brother and Magdy the obstreperous accomplice.

The two first met in 2012, during Sabahi’s first presidential bid. They later discovered they both come from Sabahi’s home town of Baltim in the northern Kafr Al-Shiekh province.

Wael, a garrulous activist from the Sa’idi province of Asyut, and Mohaymen, who has the daunting task of overseeing electioneering in four of the Sa’id’s provinces, are planning to remain behind and get out the vote. The Sa’id is the most impoverished region in Egypt, and has long been neglected by Cairo’s centralised government.

Wael, proud of his Asyut heritage, has a lot of admiration for Sabahi and his Nasserist ideology. For him, Gamal Abdel Nasser —the former nationalist leader who led the 1952 coup against Egypt’s monarchy —was the only president who cared about the south and its development. But its conservative politics and hierarchical social structure makes it a more difficult place for activists to operate. The villages are even more unwelcoming, Wael says.

“In my village, no one moves unless I’m there. But once I’m there, they’re happy to stand me in front of the cannon,” he brags, grinning broadly.

It’s a 300-mile journey south and the minibus, exposed to strong headwinds, fishtails from side to side for most of the way. Mostafa leans back and confesses he’s exhausted.

“We’ve left our studies, our work and our income, because we know if Sabahi’s elected we’ll be able to hold him to account,” he says.

But there’s nothing else he’d rather do. Mostafa boasts that he had projects outside of Egypt but gave them up to continue the struggle. He looks at Magdy’s sleeping figure and laughs. “No wonder it’s quiet,” he jokes.

Mohaymen has also been run ragged, juggling his end of term exams and the campaign. But he believes the campaign team’s spirits are high.

“We’ll learn from each experience,” he says. “We continue to learn every step of the way.”

They speak fondly of their experiences during the uprising and the protests that followed. Their activism has taken them across Egypt, opening up networks and establishing new connections. They’ve learnt to interact with the older generations and their legacy of dissident poets and artists.

They’re full of revolutionary zeal. They find it hard to speak about anything else. Mostafa’s ringtone is a Sabahi campaign song.

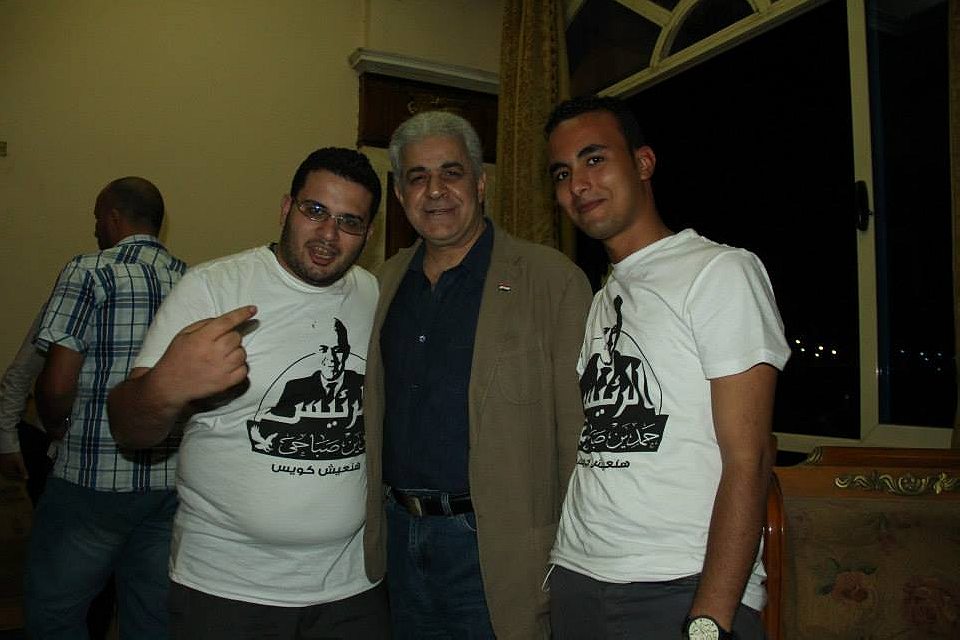

At 4:30pm, the minibus pulls into the narrow, dirt driveway of the riverside Nile Hotel. There’s no time to drink in the view. The four make a mad dash to the reception, ready to begin coordinating Sabahi’s upcoming conference with their Sohag counterparts. The white campaign t-shirts with Sabahi’s face and trademark smile marks out the otherwise ragtag bunch.

The opposition candidate and electoral underdog has a hectic schedule ahead of him. Village elders and political supporters from across the Sa’id have come to meet with him. While the elders are inside sharing their grievances with Sabahi and discussing his programme, the young campaigners are outside bargaining with each other, keen to get their hands on the fresh stock of campaign materials.

“You’ve got to send the banners to Sheikh Ahmed (a village elder),” one campaigner tells Magdy, who looks slightly bemused. “If you don’t, they’ll never reach us.”

In another corner, Mohaymen lends a sympathetic ear to the slighted Luxor delegation, who were left out of the meeting in the pandemonium that followed Sabahi’s arrival. “We’re not like the other Sa’idi provinces, you know,” a man remonstrates. He’s wearing a pencil moustache, grey suit and a tie decked out in multi-coloured lotus columns. “Luxor is a different case. We rely on tourism, and that has its own problems.”

Mostafa is busy showing his Sa’idi counterparts the latest flyer, a satirical debate between the tight-lipped and publicly absent Sisi and his forthcoming rival. The ex-army chief has refused to take part in a televised debate, let alone make a public appearance, citing security risks. And in lieu of an electoral programme, he has stuck to vague rhetoric and carefully edited television interviews.

Amidst the deafening garble of Sisi-mania, the flyers are a refreshing bit of humour for the campaigners.

The four firebrands from Cairo enjoy the attention. Magdy, wearing one earphone and letting the chord run concealed down his back, strides about, aware that he’s one of the gatekeepers to the beloved Sabahi. He’s quite smitten by his idol, speaking fondly of his Facebook profile photo, which shows the two warmly embracing.

Sai’di campaigners want their souvenir snaps as well and Sabahi always smilingly acquiesces. The admiration is palpable among the young activists. His revolutionary message of dignity, freedom and social justice resonates with them.

For them, there’s no going back to how it was: to single-candidate elections, unchecked police brutality and rampant corruption.

For Mostafa and many other formerly disillusioned youth, the 18 days in Tahrir Square serve as reminder that change is possible

“We grew up feeling that something was not right, but we didn’t know anything else,” Mostafa says. He became politically aware during the Iraq war and then threw himself into the Kefaya (Enough) movement in 2009 that opposed the hereditary transfer of power—Mubarak looked set to hand over the country to his son. But he left soon after, frustrated and looking for employment in neighbouring Libya. For him and many other formerly disillusioned youth, the 18 days in Tahrir Square serve as reminder that change is possible. The dreams dreamt during that cataclysmic month continue to motivate Egypt’s young revolutionaries.

“Hamdeen [Sabahi] relies on us. He knows how important our voice is,” Mostafa says coolly. “They don’t call him the youth’s candidate for nothing.”

He points to the two recent uprisings as evidence. “In three years, Egypt’s youth have removed two presidents,” he says, referring to the overthrow of Mubarak and subsequent removal of Morsi. He’s confident Egypt’s youth will rise up again if necessary. Sisi knows this, Mostafa tells me. “He knows he’s lost the youth.”

But if the aftermath of last year’s coup is anything to go by, an Egypt with Sisi at the reigns will be a grim, oppressive one. The brutal crackdown on the Muslim Brothers, human rights activists and journalists following the July 2013 coup has seen tens of thousands arrested—mostly youth. A punitive legal system, emboldened by the changing tide, has seen one judge sentence hundreds to death with one stroke of the gavel. These are all troubling indications of the re-emergence of Egypt’s totalitarian state.

Back in the minibus, en route to the next rally, Mohaymen shrugs these troubles aside. “There’s no room for anxiety now. I’m feeling good about today. Everyone seemed happy in the end, even the ones who initially felt neglected.”

“I’ve got to focus on the coming days, make sure I cover all my provinces… energise our base, you know.”

Perched over their take-away dinners, the four hardly exchange glances. Magdy pipes up but is quickly silenced by a collective moan. But the silence soon turns to laughter when Mostafa, whining about the rubbery pasta, reminisces about a dish he once had abroad.

“Meat and milk in the same dish?” Wael teases. “That’s mental.”

As the crowd of local campaigners begins to thin out, the four wearily check social media and set about updating their campaign’s Facebook page.

Magdy takes a deep drag of his shisha and stares off into the balmy Sohag night, oblivious to the hubbub of the Nile Hotel’s back garden and the perturbed local campaigner who is trying to grab his attention. He’s exhausted, but ensconced in his garden chair overlooking the Nile, he kicks back for brief moment. After weeks on the campaign trail, he’s well aware that his man likes to go the extra mile, and soon enough it will be time to work again.

And then, like clockwork, Sabahi re-emerges from his hotel room at 1:30am, ready for one final meet-and-greet.