An ambitious program is bringing modern tech to Mongolia’s 800,000-strong nomadic population.

TSETSERLEG, Mongolia—

As the crow flies, Gaaj, one of Mongolia’s 800,000 fully nomadic citizens, doesn’t live too far from Ulaanbaatar, the country’s capital and only metropolis. His yak-felt-and-wood tent, or ger, stands in a valley 360 miles away, just outside of Tsetserleg, the administrative and commercial nexus of the Arkhangai province.

But crows and maps are deceptive in Mongolia—they hide how rapidly Ulaanbaatar’s urban sprawl gives way to endless open plains and isolation. At 603,910 square miles, Mongolia is the 19th largest nation in the world, but with 1.2 of its 2.8 million citizens live in the capital with the rest in far-flung villages or living nomadically like Gaaj. It has the lowest population density of any sovereign nation. Underlining this fact, the trip out to Gaaj’s ger from the Dragon Bus Station on the eastern fringe of Ulaanbaatar is eight hours of an unending procession of yak dung and skulls dotting the plains.

Yak meat jerky so hard it has to be broken with an axe

These remains bear testament to the comings and goings of nomadic herds. Although elsewhere in the nation you’re apt to wander into valleys choking with goats or sheep, yaks predominate in this region, where herders rely on them for almost every necessity. Yak fur socks and yak felt walls keep them warm. Yak meat jerky so hard it has to be broken up with an axe and boiled like shoe leather, served with hot and salty yak milk-and-butter tea, fills their bellies. Tiny balls of rock-hard cheese, tucked against the cheek and sucked over long rides, keep them occupied as they navigate the unpaved hills on tiny, plodding, sturdy ponies.

Although motorcycles and a smattering of cars help a nomad get to town on short notice, these steeds (or camels in the Gobi Desert) are the best way to move tiny herds in slow, regular annual orbits around the towns and markets the herders frequent to sell their excess meat and crafts, moving forward as the grazing gets scarce. It’s not an easy life, but the connection to land and livestock is what they’ve grown up with. And the city, smoggy with coal fire, often more expensive, and lacking in easy, secure work for those with few skills or experience that don’t involve milking or shearing, doesn’t hold much appeal unless your herd is shrinking or dying, or you’re desperate for cash.

Even Tsetserleg is only a blip, quickly swallowed up by the smooth slopes of the central steppe’s Khangai Mountains. Cresting a pass in the hills, we see the two gers where Gaaj’s family lives in a valley, but nothing else. No power lines, no hum of traffic, not even another family’s camp breaks the isolation of the valley as far as the eye can see. Yet somehow when we duck through the tent’s tiny wooden door we find Gaaj’s family sprawled around a color TV watching a screening of 3:10 to Yuma (the more recent Russell Crowe version) broadcast with Mongol subtitles from a station back in Ulaanbaatar.

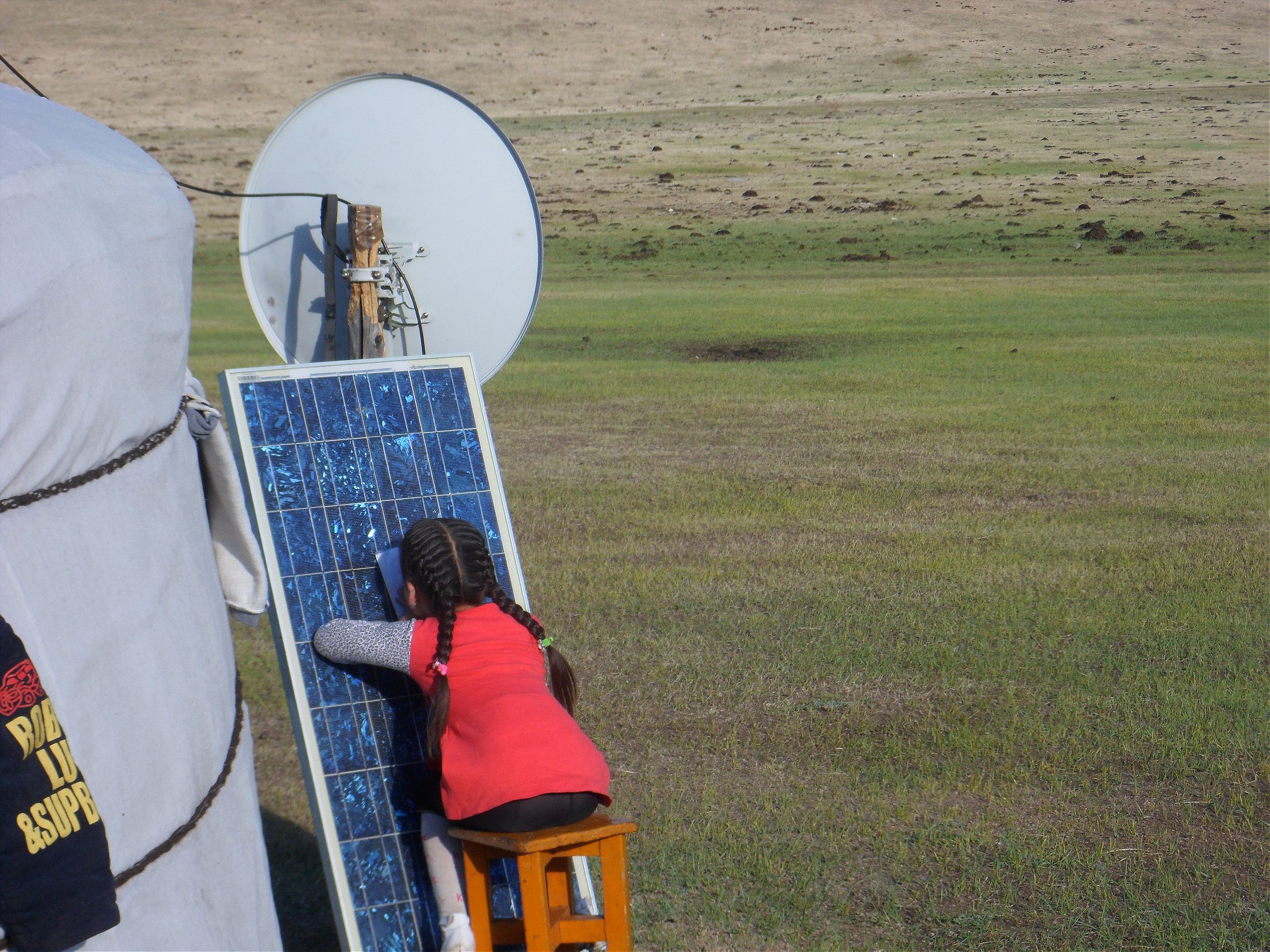

For all their isolation, Gaaj’s family lives on the grid, connected to broadcast waves and cell signals by the trusty solar panel tilted up on a post between the gers. Gaaj, a thirtysomething man with a hoof-shaped indentation on his face (almost certainly from a horse, but misplaced politeness keeps me from asking outright) and skin so weathered he looks closer to 50, is an entrepreneurial nomad. He has a car that he uses to run a rural taxi service for other nomads, and he’s the go-to host for foreigners passing through Arkhangai. Though hardly rich, even by Mongolian standards, he makes a bit more than the $3,780 average annual salary reported by goat, sheep, and yak herders in a 2010 study of nomad incomes in eastern Mongolia.

But his modest wealth didn’t buy him his solar panel, nor is he unique in having one. Gaaj is one of the beneficiaries of the Mongolian government’s “National 100,000 Solar Ger Electrification Program.”

Before I left Ulaanbaatar, I overheard a guide named Bold tell two older tourists, “You can charge your phone in the gers,” adding, “The gers all have these panels now.”

The project began in 2000, just as Mongolia’s boom years were kicking off following the discovery of some of the world’s largest untapped coal, copper, gold, and uranium deposits. These new resources revolutionized the economy of a nation that had until then survived mainly on cashmere and dairy. The wealth generated by mining developments—the Gobi Desert’s Oyu Tolgoi mine alone, built in 2010, is set to boost the national economy by one-third within a decade—created an inexorable nomadic moth-to-the-light process of mass urbanization. (In 2000, Ulaanbaatar was just 61 percent of its current size.)

While Ulaanbaatar’s skyline is dominated by construction cranes and newly minted skyscrapers, its fringes are made of nomadic gers fixed in place. Drawn in by a sense of missing out on wealth and development (nomadic salaries are still only 65 percent of the national average, and far lower than those of the rising Ulaanbaatar middle class), nomads feel compelled to abandon their lives to become a part of the nation’s development. Most end up living in slums, working as menial laborers.

“The government of Mongolia was keenly aware of its rural residents’ predicament,” write World Bank energy specialist Peter Johansen and consultants Ivy Cheng and Roberto La Rocca in a 2014 review of the project, “and was committed to bring about development … while preserving the herders’ traditional lifestyle.”

The government decided that the best way to do this would be to get solar panels in as many homes as possible. In the early years, the program looked like a failure. Limited in its capacity over such a massive area, the central government could only distribute and repair systems out of the capital. Plus, even with subsidies, the smallest wattage setup still cost about a year’s salary for an average nomad while the largest capacity cost two years’ wages. In 2006, six years into the project, they’d only managed to unevenly distribute 33,000 systems. Then, in 2008, international donors stepped in, led by the World Bank, and for once actually delivered as promised.

The project was flooded with $12 million in grants from the World Bank, the International Development Agency, and the Dutch government, a surprisingly proactive ally of the Mongols who also helped to reintroduce a population of wild Przewalski (Takhi in Mongol) horses to the country. The cash boosted the subsidies, slicing prices in half, and helped with the logistics of trucking panels out to the most remote corners of the country.

Another crucial contribution came from XacBank, a local Mongolian microcredit union and the first business to operate branches in every small region and village of the nation. Leveraging relationships between nomads and their local soums (the nearest market or village), the bank built on word of mouth and casual relationships to create local networks of credit providers, advice givers, and servicers to follow up on loans. Following in Xac’s footsteps, the World Bank managed to move the panels beyond Ulaanbaatar, setting up local sales shops and training 400 businesspeople in maintenance and service in about 50 locations spread evenly across the physical expanse of the nation. In short, they cut the costs and distance, created a warranty and service network, and started a cascade of positive word of mouth nationwide.

In 2008, when the World Bank launched its new network, almost everyone had given up on the government’s original 100,000 ger goal. At best, officials hoped, they would get to 80,000. Instead at the program’s close in 2012, just four years later, they’d distributed 100,146 solar panels serving 70 percent of all nomads in the country. And emboldened bureaucrats now hope to achieve universal rural electrification through solar power by 2020.

Before the program, about 90 percent of nomads relied on candles, coal, and yak dung to light and heat their homes, shelling out more than the cost of a solar panel in the space of a few years for smoky and inefficient power. Just over half managed to power a phone or radio with a diesel generator or motorcycle battery, draining more of their meager budgets. In cutting down on energy costs and increasing availability, the solar panel program freed up cash, creating a brand new industry of small appliance providers in the countryside. The industry is so robust that now 70 percent of nomads have a color TV and satellite dish and 90 percent are hooked into a mobile phone network.

Those mobile phones and televisions, in turn, have hooked nomads for the first time into the information superhighway. Gaaj now has access to weather reports and makes phone calls to markets to manage his livestock, keeping more animals alive and fetching a higher price for their wool, milk, and meat. His phone allows him to stay connected with young family members attending boarding school in the towns and to seek out medical advice from distant clinics.

Of course, there are still some limitations. On a visit to one of Gaaj’s relatives, a young woman slips out of the ger for several hours. Gaaj later tells me through a translator, “She wanted to use her phone, but there is no signal here. She rides to the top of the mountain every day to speak to our family.” It’s an hour’s trek up the mountain, but before she got the phone she was often out of touch with relatives for weeks or months at a time. “The phone has, to a large extent, replaced the need to embark on often long and arduous journeys just to deliver or pick up a message,” write Chung, Johansen, and La Rocca.

“We save on candles, we can finish our daily tasks without having to postpone them, and we can sell our meat at a higher price because we have better access to information thanks to our TV and phone,” a nomad from the Khentii province told World Bank consultants in an in-depth interview. “If somebody shows up at the ger, we can check the market price now. Before [the panels], we used to accept whatever figure the other person would suggest.” These little things add up into an infinitely more secure, connected, and profitable lifestyle.

According to figures from the World Bank and the Mongolian government, nine out of 10 panels purchased more than six years ago, before the warranty and repair program kicked in, were still working, and more than 90 percent of those surveyed found the current reliable and sufficient. Seventy percent of customers reported increased productivity and leisure time, with most families staying up an extra one to two hours to relax and unwind by lamplight.

“Perhaps we spend more time working at night, but the real impact is that we now carry out our work in a relaxed manner. We don’t have to rush to get things done before it is dark anymore,” a nomad from Kentii told the surveyors. Ninety-three percent said they were overall satisfied with their panels, and 100 percent said they had or would recommend them to anyone who asked.

There have even been reports in recent years of nomads who had moved to the soums and capital for work moving back to the countryside after hearing how much easier it’s become to hack it as a herder.

Granted, Gaaj’s life is still no idyll. One morning, he stands outside the ger as clouds roll in and a wind cuts through the hills. A man of few and exact words, he rubs his hands, stamps his feet, then shakes his head and just says, “Cold … very cold.” Temperatures in his valley sink to -22 degrees Fahrenheit in the winter, and if anything goes truly wrong, even if he can call a hospital, getting there in a nation three times the size of France with only one major paved highway a bumpy 30-minute drive away is a daunting prospect.

Nomads organized a horseback demonstration in Ulaanbaatar

Many nomads believe that the power of mines, 90 percent of the national economy today, allows mineral extractors and developers to flout laws protecting the forests, water reservoirs, and grazing grounds vital to nomads from degradation.

The sense of encroachment made national heroes out of four nomads who, in 2010, opened fire with their old hunting rifles on an empty mining camp and, the next year, organized a 100-man horseback demonstration in Ulaanbaatar, firing arrows at the Government House. In 2013 President Tsakhia Elbegdorj won his second term on a platform of tighter foreign mining controls. And even with these boosts to the rural economy, more than 800,000 Mongols, many of them nomads, still live below the national poverty line.

Their way of life is under threat, and they have not achieved parity with their urban kin. Some contend that these forces are breeding a nascent anti-mining, pro-traditionalist eco-terror movement. Tsetsegee Munkhbayar, one of those who fired on the mines, and his Gal Undesten movement now stand accused of planting bombs outside government buildings in 2013. “We are a small group of simple herders fighting powerful people,” Munkhbayar told a New Zealand journalist in 2011. “It’s not an easy fight but we cannot stand by idly and watch our land and way of life come to an end.”

But Gaaj is a savvy and entrepreneurial man. He has the tools to utilize his wits and to sustain his family without just scraping by now. The flimsy tinfoil-looking contraption outside his ger is enough of a lifeline to stand on and fight from, and that’s worth something out in the brutal emptiness of the steppe.