At France’s Piémanson beach, families build cabins on the sand and wait for the day their paradise will be shut down for good.

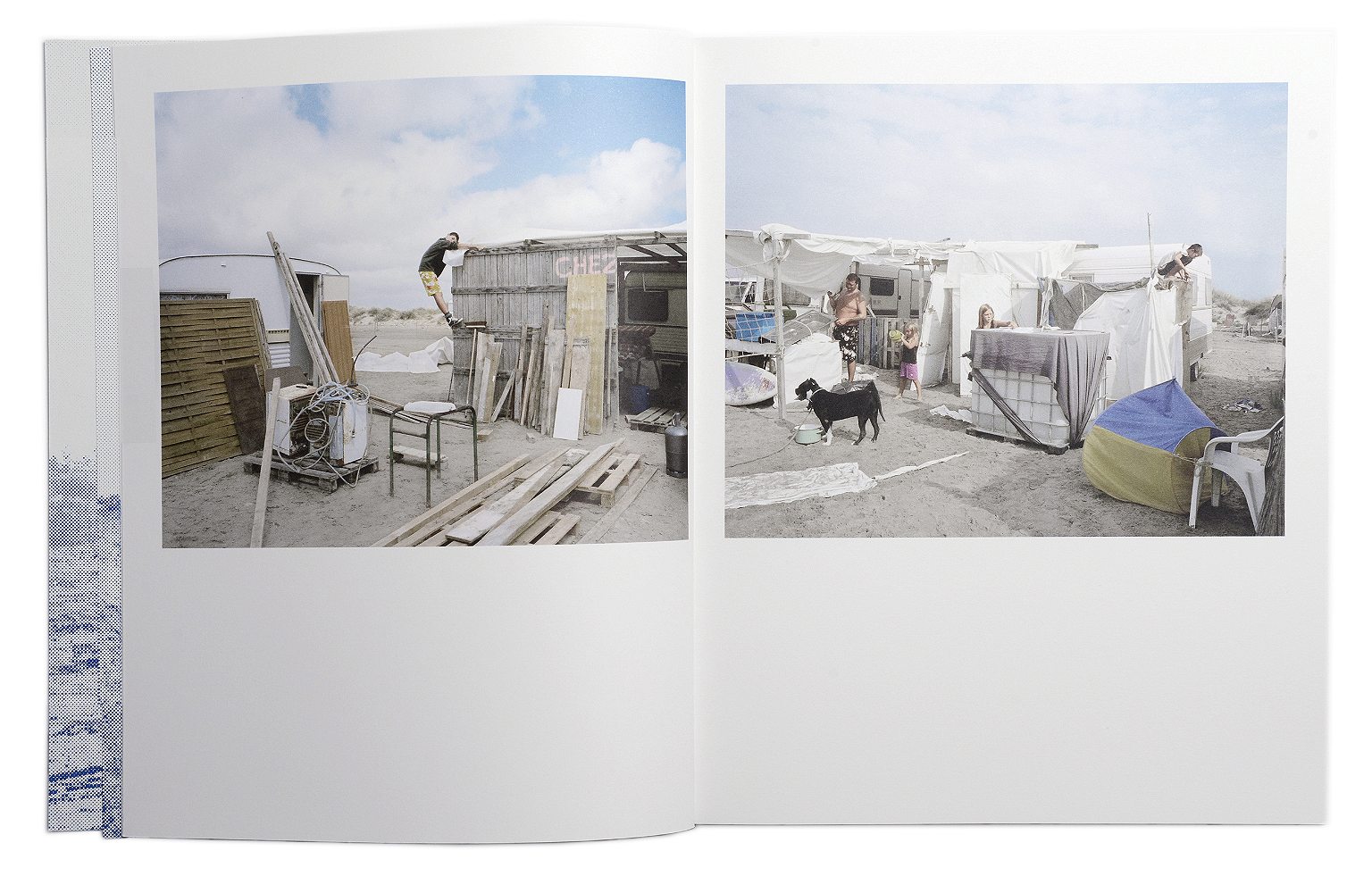

Every year on the first of May, families flock to the beach at Piémanson in the south of France. May 1 is both a public holiday and the day the beach opens for the season, and though it’s often too cold to go in the water, people have picnics while their kids enjoy the sand for the first time of the year. When the sun sets, the women drive back to the city with the children, leaving the men on the desolate, cold beach. For a week, they’ll be busy building cozy wooden cabins on the sand, sleeping in their cars to ensure everything is set for the summer ahead. How can they get away with this? It turns out that Piémanson, located in the Camargue coastland, is France’s last remaining “wild beach.” It’s not regulated in any way–and is therefore completely free–and thousands of people from the region and all over Europe camp here to get away from the bureaucracy, the clutter and the crowds of city life. Vasantha Yogananthan photographed Piémanson for five consecutive summers. This year, he self-published a book about daily life in this unusual refuge. He joined R&K from his home near Paris.

Roads & Kingdoms: What exactly is a “wild beach”?

Vasantha Yogananthan: In France, littoral law says that you can’t camp on a beach for more than one night. Piémanson’s particularity is that it exists outside of the law. People park their caravans there, they build small cabins in which they stay for a few weeks, a month or even the whole summer. That’s why it’s called a wild beach. It also refers to the fact that there’s no water and no electricity. You don’t pay to camp there, so there’s nothing. You are in the complete wilderness of the Camargue.

R&K: Why hasn’t Piémanson been shut down yet?

Yogananthan: In Camargue, there’s a strong tradition that dates back to the early 20th century when fishermen would build small cabins to protect themselves from bad weather. After World War II, when a fourth week of paid vacation was instated and people started taking more time off, those who couldn’t afford to go anywhere else went to the beach and built cabins for the summer. In Piémanson, it’s these same families that have been coming back for 30, 40 years. There’s a strong sense of history there, and an idea of transmission between generations. It made me come back myself, to understand why people who came as children were bringing their kids to the same place today.

R&K: So because of this history, authorities turn a blind eye?

Yogananthan: Yes. There are policemen who come to make sure everything is going well, but apart from that it’s a place that exists outside of the law. It fluctuates however because there have been a lot of projects to shut this place down and replace it with a proper camping site to develop tourism and the economy. But the beach is located inside a park and there’s a salt company that operates there.It’s very complicated to make a decision because it entails an agreement between the mayor of Arles, the prefect, the park authority, the minister, etc. There are a lot of actors at play, and on top of that, there are the people who want to keep their beach. Also, no mayor wants to lose votes by shutting down the beach.

R&K: So how did you find yourself in Piémanson?

Yogananthan: I was at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2009 and I wanted to escape the festival for a day. I asked a local in the street if he knew a beach that wasn’t too full of tourists and he told me to go to Piémanson. So I took the bus and when I arrived there, I saw all these cabins and wondered what the hell was going on. What’s great about Piémanson though is that when you’re not a regular, you’re quickly invited by someone for a drink or for dinner. And that’s what happened to me. I met a couple of families and started thinking this place could make for a great photo project. I came back a few weeks later, and then a little bit longer every year for five years. The goal was to live with these people in the same way they did, so I came with a tent and I didn’t leave the beach and I got by just like they did.

I took photos of adults playing with kids and I wondered who was really playing with whom

R&K: What was it that kept you coming back every year?

Yogananthan: A lot of things. I was very interested and surprised to see how a community had emerged in Piémanson that wasn’t an ideological gathering like the Rainbow Family for example, or Burning Man. People don’t come together to protest against something there, they’re not anarchists who want to abandon city life or reject the consumer society. They’re just like us, but they have developed a special relationship to a place since their childhood – a place that happens to be wild. It’s also interesting to see how much they invest in a place that has nothing. They just turn it into whatever they want. And you can see how creative people are; the architecture of the cabins changes every year and people are very proud of their ephemeral homes. They visit each other’s cabins and help each other build. For example, the electrician will install electricity in his neighbor’s cabin while another guy will do his woodwork. There’s a solidarity that doesn’t develop in normal camping sites in France, which are, at the end, reproductions of the private property system with fences and families staying amongst themselves.

R&K: How many people live together in Piémanson?

Yogananthan: About 3,000 to 5,000 people live on the beach in July and August. It seems completely crazy to think that all these people are in a place where there’s nothing, but they manage to make it work. In five years, I’ve seen a couple of arguments or fights, but it’s not at all a dangerous place. Instead, the spirit of conviviality and of sharing is simply very beautiful and very powerful. This was my first longterm project as a young photographer, and when you finish something like this, you tend to ask yourself why you’ve worked so much on it. Five years is a long time, and people kept asking me why I continued. Piémanson has been photographed a lot, it has been romanticized as a place where poor people spend their summers and play boules and have drinks. But I wanted to have a more subjective, more subtle approach, showing what daily life is like on a wild beach. A beach that people come back to every year and where neighbors are friends and kids find things to do even though there’s nothing. A lost paradise where adults revisit their childhood. I mean, the very process of building a cabin reminded me of children building a fort. It brought up memories of Robinson Crusoe on his deserted island. I took photos of adults playing with kids and I wondered who was really playing with whom.

R&K: How has this project changed you?

Yogananthan: I would say it changed me in two ways. Living with them, witnessing this spirit of exchange and giving, taught me things as a human being. These are people who tend not to have very much, yet you can arrive in Piémanson without water or food, and you’ll always have a place to eat or sleep. It might seem a little cheesy, but when you witness this, it makes you think about the types of human relationships you create whether it’s at work or with your friends or with strangers even. The project also changed my perception of photography. I come from a photojournalism background where generally you need to work fast and produce images that are easy to understand. The first summer I photographed Piémanson, I only scratched the surface. Placing myself in the role of a documentary photographer was a real break from what I had been doing.

In July and August, the beach is packed and there are fireworks and parties.

R&K: How does Piémanson transform over one summer, physically and architecturally?

Yogananthan: The first week of May, there are around 100 people on the beach. All men. There are half-built cabins dotted around and the atmosphere is very unique. In July, it begins to transform radically. In Piémanson, there’s a mix of people from the region and Europeans from everywhere else. They told me they didn’t have beaches like this one in their countries. There were these Swiss truckers I saw every year who would come for three weeks; it was their break for the year. There are people from Italy and from Belgium and from the north of France… In July and August, the beach is packed and there are fireworks and parties.

R&K: And at the end of the summer, they need to take everything down…

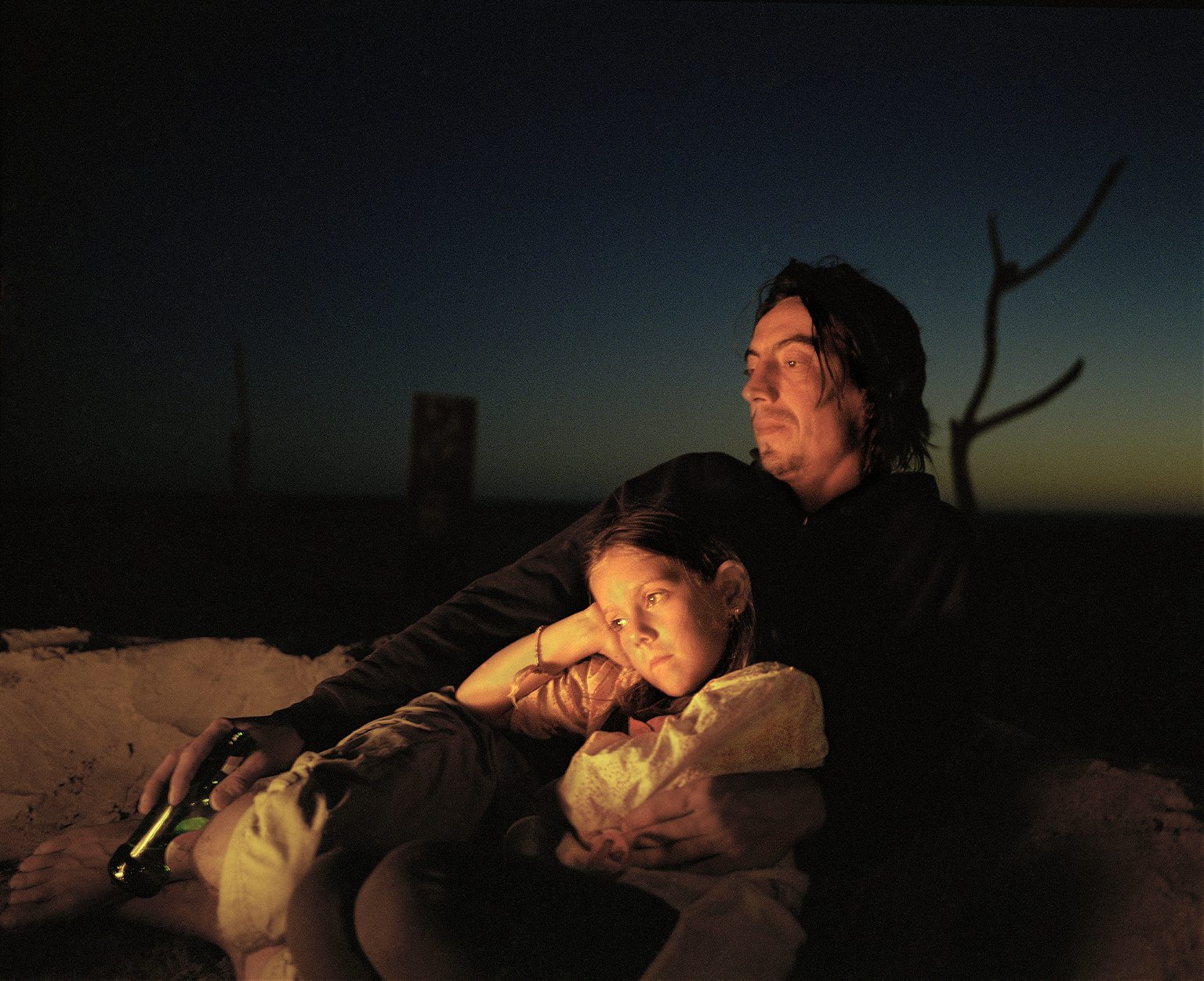

Yogananthan: In September the police come back and close the beach, so the weekend before that, they need to take everything down. There’s only one photo taken at night in the project, where you see a man and his daughter by a fire. That was taken on the last night, when they tear everything down and they burn the wood. I felt like I was visualizing the very definition of melancholia. There are many things that make Piémanson a mythical place: it’s outside the law, it’s only open a few months out of the year, it’s the only beach that has survived–there used to be three wild beaches in the region–and lastly, it’s going to be shut down soon. It really is just a question of time now. So that night, everyone thinks about how this might be the last night they ever spend here.

R&K: Why is it important to preserve places like Piémanson?

Yogananthan: Though I try not to take sides as a photographer, I personally think it’s important because I don’t understand how you can politically justify denying access to something that essential. Holidays are more than just days off. Everyone needs to escape their job. All these people told me that the day this beach closes, they’ll have nowhere to go on holiday. Perhaps they’ll be able to pay to go somewhere for a week, but that’s it. Here, they could come for as long as they want. When Piémanson closes, they’ll be heartbroken.

You can see more of Vasantha Yogananthan’s work here and check out his publishing house, Chose Commune.