A mansion. A crash site. And the spark that ignited the Rwandan genocide.

KIGALI, Rwanda—

A jet roared overhead as we approached the crash site, strolling through a garden of fruit trees at the home of the late Rwandan president, Juvénal Habyarimana. In front of us, a guard manned a small concrete tower, perched atop a red brick wall that obscured our view of the wreckage.

Walking under a massive ficus tree, past a pond that once housed Habyarimana’s python, my guide Christine motioned me toward a ladder that led to a small viewing platform. Minutes earlier I’d stood inside Habyarimana’s bedroom, explored his secret weapons closet, and the chamber where he’d practiced witchcraft. Now, I was about to see the remains of the plane in which Rwanda’s longest-serving president was assassinated—the event that ignited the Rwandan genocide.

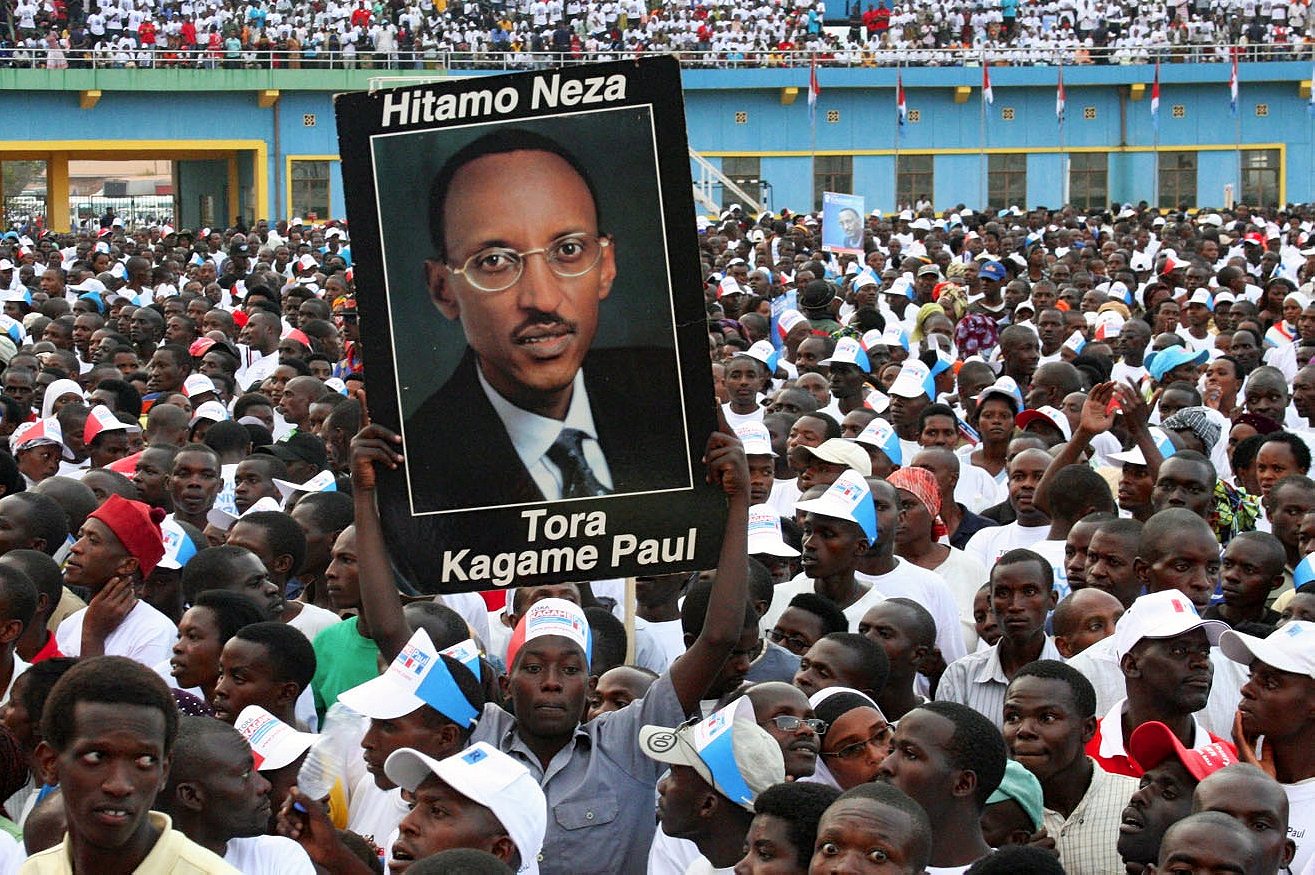

It’s been 20 years since Habyarimana’s Falcon 50 aircraft was shot down on the outskirts of Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, and the country has come a long way from the 100 days of mass murder that followed. Although political tensions still simmer and current President Paul Kagame has been accused of suppressing dissent, Rwanda is now one of Africa’s safest nations and its economy is among the fastest growing on the continent. The country that in the spring of 1994 witnessed the worst genocide since the Holocaust is now defined by a lack of crime, spotless public areas, and officials who are harshly punished if caught soliciting bribes or skimming off of public contracts. Today, aside from a handful of memorials filled with skulls, photos of the dead, and displays of the instruments of death—spiked clubs, hoes, machetes—there’s little visible evidence of the nightmare that saw the deaths of up to 1 million Rwandans, mostly members of the Tutsi minority.

The tour includes a walk through the house and gardens and a visit to the Falcon 50 wreckage

The 20th anniversary of the genocide will be commemorated on April 7, and I decided to visit the scene that triggered the bloodshed. On an afternoon in March, I made my way to Habyarimana’s residence: a three-story brick and concrete structure located a mile from Kigali International Airport’s runway. Built in 1976, three years after Habyarimana seized power, the mansion has been open to the public since 2008, when it was reborn as the State House Museum. An hourlong tour includes a walk through the house and gardens and a visit to the Falcon 50 wreckage, which sits just beyond the edge of the compound.

For an event of such significance, much about the crash remains a mystery. On the evening of April 6, 1994, Habyarimana boarded the Dassault jet in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city, accompanied by Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira, a three-man French crew, and seven additional Rwandan and Burundian officials. The group was returning from a meeting discussing the Arusha Accords, a peace agreement signed the previous August between Habyarimana’s government and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). The two had been at war since October 1990, when the RPF, a guerrilla force formed by Tutsi exiles, invaded from neighboring Uganda. Although a cease-fire was in effect, implementation of the Arusha provisions had stalled, and Habyarimana, a member of Rwanda’s Hutu majority, had been reproached throughout the day by several regional leaders. As the plane took off along the Indian Ocean coast, the mood on board was likely tense.

With characteristics of both an ethnic group and a caste—though not quite either—the Tutsi minority had traditionally ruled Rwanda, a mountainous, densely populated, monolinguistic nation that existed as a centralized kingdom long before it was a modern state. Though governed by Tutsi kings, precolonial Rwanda also reserved political space for its Hutu peasant majority, and the two groups co-existed in an orderly, integrated society.

By using Tutsi elites to rule by proxy, however, Rwanda’s Belgian colonizers had upended this balance of power, stoking Hutu resentment, and unknowingly sowing the seeds of future violence. Eventually coming to fear the Tutsi it had coddled, Belgium threw its weight behind a Hutu political awakening as it prepared to abandon Central Africa. By independence in 1962, leadership was firmly in Hutu hands. Between 1959 and 1964, facing a wave of anti-Tutsi uprisings, more than 300,000 Tutsi fled the country.

Belgium eventually came to fear the Tutsi

Three decades later, in early 1994, Rwanda sat at the edge of a precipice. Under the Arusha Accords, Habyarimana was supposed to lead the creation of a transitional government, with power shared between his ruling MRND party, the RPF rebels, and four existing opposition groups. Yet intra-party divisions, stoked by the growing clout of anti-Tutsi extremists, had repeatedly delayed the new government’s formation.

On the ground to facilitate the transition, U.N. peacekeepers began to warn of a shadowy “third force”—radical Hutus out to sabotage the peace process and prevent the RPF from assuming a role in government. In January, an informant told the U.N. that army-backed youth militias, already flooded with weapons, were drawing up lists of Tutsi in every commune, and waiting for the signal to commence with their extermination. In Kigali, radio with ties to the Hutu supremacist party CDR called for the blood of Tutsi “cockroaches.”

Then, around 8:25 p.m. on April 6, 1994, two surface-to-air missiles hit Habyarimana’s jet as it approached the Kigali airport. Moments later, the plane lay in a crumpled heap at the edge of the president’s garden. All 12 occupants, including Habyarimana, were killed in the crash. The murders of political moderates and their families, and of Tutsi men, women, and children, began within hours.

Despite several investigations into the crash, the last released in 2012, it remains unclear who ordered Habyarimana’s death. The most widely accepted scenario, which leading Rwanda scholar Gérard Prunier presents in The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide, is that the plane was shot down on the command of Hutu extremists, including members of the opposition CDR and/or the so-called akazu—close associates of the president’s wife Agathe who had long wielded a high degree of power. Among them was Théoneste Bagosora, the army chief of staff, who presided over a “crisis committee” following the crash and is considered to be a key mastermind of the subsequent killings. This version of events presumes Habyarimana’s assassins saw him as a liability to their plans to foil Arusha and commence with the Tutsi extermination—the only way, they believed, to fully guard against a future Tutsi threat.

As Prunier argues, this scenario is supported by several facts. First, warnings of “something big” had been circulating among extremist media in the days before the attack. Second, within 45 minutes of the crash, army-backed militias had established roadblocks around the city and begun to search the houses of political enemies, suggesting their mobilization had been previously planned. According to Prunier, Bagosora even called the U.N. on the night of the crash, described the assassination as a coup, and claimed he and his associates would “save the nation.”

Some witnesses reported seeing white men flee Masaka Hill minutes after the crash

Finally, witness testimonies and multiple investigations suggest the missiles—probably Russian-made SAM-16s—were fired from either the Rwandan army’s Kanombe barracks or from farther away in the vicinity of Masaka Hill, which was under patrol of the Rwandan Presidential Guard. Some witnesses reported seeing white men flee Masaka Hill minutes after the crash—possibly mercenaries hired to fire the missiles, which required technical knowledge that the Rwandan armed forces lacked.

A second theory, highly controversial in Kigali, blames the assassination on the RPF, which captured power three months later in the war that resumed as the massacres started. Although the RPF had received a favorable settlement at Arusha, proponents of the theory argue, Major General Paul Kagame, its top commander and Rwanda’s current president, ordered Habyarimana’s death to provide grounds for spoiling the cease-fire, and pave the way for an outright military victory.

Despite patrols by the Presidential Guard, it is possible that RPF assassins could have infiltrated Masaka Hill—a scenario advocated by the French judge Jean-Louis Bruguière, whose 2006 report implicated the RPF. Citing interviews with several RPF defectors, Bruguière claims a group of rebel officers, including Kagame, had plotted the attack on March 31, and that an RPF officer named Frank Nziza had fired the missile that brought the aircraft down. Bruguière subsequently issued arrest warrants for nine Kagame associates, including former Kigali mayor Rose Kabuye, who was arrested during a 2008 trip to Germany. Charges against Kabuye were eventually dropped.

Bruguière’s report has since come under scrutiny after a key witness retracted his testimony, citing manipulation, and evidence emerged that the release of the report was timed to counter a Rwandan investigation into France’s involvement in the events of 1994, which Kigali alleges included the arming and training of anti-Tutsi militias. Nonetheless, several former high-ranking RPF officials remain adamant that Kagame—whose forces have been implicated in multiple U.N. investigations into the killing of tens of thousands of civilians in Rwanda and Congo—was also behind Habyarimana’s death. These include his former intelligence chief Patrick Karegeya, who was found murdered in January in a Johannesburg hotel room, and onetime chief of staff Theogene Rudasingwa, who told Agence France Press in 2011 that Kagame had told him “with characteristic callousness and much glee” that he had personally ordered the downing of the jet. If this is true, it would mean that Kagame, the man generally credited with ending the genocide, had also played a key role in stoking it—effectively choosing the pursuit of all-out victory over hundreds of thousands of Tutsi lives.

With such delicate questions unanswered, the tour of the State House Museum stays far from politics. Instead, it provides an intimate look at the quirks of the former president. Leading me through the mansion—weathered but still fit for habitation—Christine showed off Habyarimana’s interrogation rooms, trap doors, even a chapel where Pope John Paul II, on a visit in 1990, had given a private mass. There was a trophy room with heads of antelope; a table made from the feet of an elephant; a hair salon for Habyarimana’s daughters; even separate, designated entrances for the president, his wife, and personal witch doctor. The building itself is an architectural oddity—airy, yet somehow claustrophobic, and built in a Belgian style yet set amid a tropical garden.

On the night of the crash, the President’s python disappeared. No one knows where to

Although intrigued by the house, I was eager to see the crash site. Exiting the front door, we began our walk through the garden toward the wall at the edge of the compound. As we arrived at the ladder, the guard barely registered our presence, and we climbed to the viewing platform.

And there it was, sprawled about the manicured lawn in front of us. An engine, a wing—perched on its edge—a wheel, a mangled fuselage. The plane, Christine told me, had actually ruined part of the wall, with bits of wreckage—and Habyarimana’s body—landing inside the compound. Later, when Pasteur Bizimungu, Rwanda’s first post-genocide president, occupied the house, the wall was rebuilt and the jet’s remains moved outside the garden. Somehow, Habyarimana’s body ended up in Congo, where then-President Mobutu Sese Seko, a longtime friend, kept it on the grounds of his jungle palace. In 1997, a day before his overthrow by RPF-backed rebels, Mobutu had the body cremated.

As Christine finished her monologue, and the din of the passing jet faded, we stared down at the wreckage in silence. Somehow, at the crime scene that sparked one of the 20th century’s greatest atrocities, the mood was tranquil: a gentle breeze, a view of the surrounding hills, birds chirping in the afternoon sun.

Pondering the mysteries of the crash, I followed Christine down the ladder and we continued our walk around the compound, stopping at a concrete pool where Habyarimana had kept his python. Apparently, the president was quite fond of the snake, rumored to weigh more than 300 pounds, which he used for various black magic rituals and employed to guard against evil spirits.

On the night of the crash, Christine told me, debris from the plane had damaged the pool, and the python disappeared.

“Up to today,” she said, “no one knows where it went.”