On the eve of voting in the European Parliamentary elections, Britons have been shocked—shocked!—by the racist things their leaders say. But a traditional toy called the golliwog tells you plenty about the ongoing problems with race in the UK.

Tomorrow, the UK will vote in the European Parliamentary elections, held once every five years. The unexpected contender in this cycle is the United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip). Their high visibility and frontrunner status comes as a surprise, given their historically poor showings in local elections and failure to win a single seat in the House of Commons over their 20-year history. But the real shock in the campaign has come from the mouths of Ukip candidates themselves.

The party’s leader Nigel Farage suggested fear was an appropriate response to living next to Romanians. A lesser Ukip candidate rendered Farage’s comments almost quaint when he earlier asked why British Olympian Mo Farah could be “an African” and still run for Britain. Still another suggested that UK comedian Lenny Henry should go back to a “black country”. Those statements and others have turned what could otherwise be a staid restocking of the bureaucracy in Brussels into a tabloid-splashing national pub fight about just how racist Britons should be allowed to be.

It seems as good a time as any, then, to consider the golliwog.

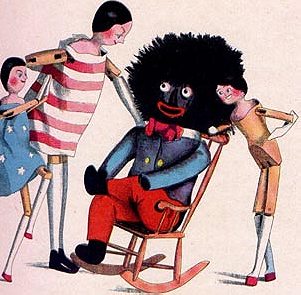

Golliwogs, as those who grew up outside of Australia, New Zealand, or the United Kingdom will probably not know, are basically blackface Raggedy Ann dolls. The clownish, oversized, and disproportionate minstrel figure descends from a friendly, shambling character in the American-British children’s writer Florence Kate Upton’s 1895 The Adventure of Two Dutch Dolls and a Golliwogg. The comedic depiction of a semi-animate black sidekick was recycled and disseminated in the early 1900s in English kid’s writer Enid Blyton’s series of Noddy books. It’s a type of ethnic caricature that, although far from eliminated from much of the world, fell outside the mainstream long ago. But in the three countries where the Golliwog image became most popular, the figure had a surprisingly long shelf life, avoiding any real backlash until the 1980s, persisting in the mainstream until the 2000s, and only thereafter facing periodic ebbs and flows of public criticism.

The why of the longevity of this peculiarly chummy racist trope stems partially from the commercial history of the image and its nostalgic resonance for children-turned-adults. But it has as much to do with the ease with which issues of race can be skirted in the countries where Golliwogs continue to be openly cherished.

Towards the end of 2013, a year of chatter on immigration and national identity, the UK saw a perhaps related string of golliwog-initiated non-conversations on race and history in the UK.

A judge ruled that any use of the term golliwog in the presence of a black man was inherently offensive

In September, the charity Oxfam was slammed and was made to apologize for selling golliwog dolls in its shops, while a septuagenarian shopkeeper in the Shetlands was publicly criticized on prominent poet Lemn Sissay’s blog for nonchalantly selling golliwog memorabilia. In November, a councilwoman for Brighton and Hove City, Dawn Barnett, took a blasting for her support of local shop owners’ rights to sell golliwogs as nostalgic, thus non-racist, trinkets, and a school in Scotland came into the national spotlight for its restoration of a controversial 1936 mural of Alice in Wonderland, featuring a galumphing golliwog.

And just before the close of the year, a Lord Justice in the Court of Appeals ruled on a 2009 case in which a black kitchen employee sued his boss for using the term golliwog (though not in reference to him). The judge ruled that any use of the term golliwog in the presence of a black man was inherently offensive. The cases ranged from those inspiring universal outrage to those raising eyebrows and those causing activists to bash their heads over counterproductive, broad stroke overreactions. But all of them raised the profile of golliwogs beyond anything that’d been seen in over a decade, and revealed that, although Brits have managed to scourge golliwogs from their pop culture and advertising, the image, term, and all of its attendant racial baggage holds strong just below the surface of many a British psyche.

That resonance comes from the fact that, for a time, the image of the golliwog was everywhere in Britain—especially everywhere that it might make a favorable synaptic association in the forming mind of a child. As a pre-cursor to the Orion costumes, contortionist routines used golliwog getups in their acts. The minstrel was more prominently used as the mascot for Blackjack, an aniseed chew, and for Robertson’s Marmalade, a ubiquitous brand with an aggressive and catchy advertising wing including mascots, dolls, and badges, up into the 1980s. Golliwog tokens were used in Robertson’s redemption competitions and schemes, sent back to corporate in exchange for golliwog figurines. It’s basically the same cultural force as Ralphie Parker’s Ovaltine decoder ring is in the U.S., except on a massive and multi-faceted scale, and with much more blackface.

In the UK, race often seems to fly under the radar compared to vitriol about class or nationhood

None of that is any more shocking than the sad history of overtly racist cultural mainstays in my home country, the U.S. The land that brought the world Aunt Jemima, “mammy,” and the magical Negro literary trope—among hundreds of other still extant stereotypes wiring racial bias into cultural bedrock—is in no place to tut-tut the UK from a moral high horse. The States are actually responsible for the golliwog to begin with, as Upton grew up in and learned from the environs of Flushing, New York. But in the UK, even now as immigration and identity draws into mainstream political debate, race often seems to fly under the radar compared to vitriol about class or nationhood. The golliwog in particular escaped any real mass scrutiny far longer than you’d expect.

Somehow it wasn’t until 1983 that anyone managed to organize a concerted protest against the use of golliwogs in advertising. Jodi, the marketing manager of the collectors’ guide and sales site All Things Golly, identifies this rising tide of protest—what she refers to as the “sensationalization” of the history and image of the figure—as the turning point in golliwog fandom. A London boycott of Robinson’s jam led slowly to the end of golliwog-based TV ads 5 years later. But the badge redemption scheme did not end until 2001, when complaints against golliwogs grew more common and vociferous. Yet even through the 2000s, sales in golliwog memorabilia, including bespoke dolls crafted for collectors by independent toymakers like Pete Wood, held strong until very recently. “I would say sales dropped off about five years ago,” says Wood. It was only then, over 25 years after the first protests of the image, that court cases explicitly addressing the racial issues of golliwogs, like the one settled last December, made their way into the judicial system and the press.

The community of golliwog collectors remains large and undaunted

Even if general interest and sales are finally waning, the community of golliwog collectors remains large and undaunted. Although the International Golliwog Collector’s Club hasn’t printed a new issue of its magazine in a while, updated its website since 2008, or held a conference since the 2007 convention in Portland, Oregon, its listserv is still active. All Things Golly receives around 3,000 to 4,000 visitors per week. One collector, Nick Martin of Fareham Hants, revealed the extent of his collection when he offered 300 golliwog items to the local Westbury Manor Museum for display in 2007. And at least four artists in Australia, New Zealand, and the UK still produce golliwog dolls to meet the demand of these groups and their members. The call for these increasing scarce relics of benign racism has risen so high that a Robertson’s badge might sell for up to £1,000 each, while a mint German Steiff golliwog doll from 1908 sold for £10,000 in 2009. And, according to Jodi, “Now we are seeing a complete resurgence of the Golliwog dolls and they have been making a comeback in toy stores and gift shops all around the world.”

Speculating as to why there’s still such (perhaps resurging) demand for golliwogs, Ferris State University professor David Pilgrim, who curates the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia in Big Rapids, Michigan, notes that, “Some people collect objects because they believe the items will increase in value. Others collect as ways to buck what they perceive to be as political correctness. Still others collect these objects cause the items remind them, in a nostalgic way, of happy times.” Although the first two motives may be at play in golliwog collecting communities, it’s mainly the nostalgia. That yearning for a symbol of British childhood and a simpler time may implicitly tie into the general uncomfortable conversations on the place, identity, and direction of the British nation in the world that have put Ukip in the press. But even if the apparent resurgence in golliwogs were unrelated to the national mood, the timing is extremely unfortunate.

Many who collect for nostalgia absolutely believe in the innocence of the dolls. They feel abused by accusations that their hobby and holdings are offensive. “I have to say that for me, gollies were just childhood toys and the badges part of our childhood here,” says Wood, who still stresses that, while he makes golliwog collectibles, he does not collect them himself. “I have never understood those that make claims about racial issues.” All of the collectors he’s worked with he describes as lovely people with a pure view of a blameless collectible. To Jodi, the criticism that collectors face is nonsensical because, “at the end of the day, it’s just a doll—a toy,” she says. Ged Grebby, founder and chief executive of the British advocacy group Show Racism the Red Card, summarizes the attitude of these collectors by referencing a common defense of those who own, do, or say questionable things: “[the dolls] aren’t meant to be offensive, so they aren’t offensive.”

Much of this seems to stem from a certain lack of logic and introspection in the way the golliwog collectors understand what people mean when accusing them (or, more properly, their collectibles) of carrying racist overtones. “Really, their negative attachment to Golliwogs has gone purely because our world is not a racist place anymore,” says Jodi of collectors and, apparently, of the state of minorities and skin color in the Western world. “Because we are truly a global melting pot. The segregation just does not exist and the way people look at things are very different now then they were 100 years ago, even 30 years ago.” Jodi goes on to accuse people who call golliwogs racist of creating drama and racism by pointing out a problem that no longer exists. She feels that the demands of those offended by the dolls are irrational, citing criticisms of Barbie dolls for being only white many years back, and justifying the golliwog as an answer to that call for more multi-ethnic and inclusive playthings. This inability to acknowledge the contours of racism beyond openly violent bigotry and segregation, and to understand why a blackface minstrel might not be what people are looking for in an ethnically inclusive doll, is symptomatic of cultures and homogenous communities rarely confronted with conversations on race or the realities of inequality in the modern world, then suddenly thrust into a growing tide of national debate. It cannot even be classified as willful ignorance as, when one does not encounter the arguments, it’s hard to purposefully ignore them.

This occasional strategic ignorance in the collector community ignores some of the most blatant cases in which golliwogs have been used for expressly racist purposes—the kinds that Jodi believes do not exist in the modern world. Another 2013 court case saw a worker awarded £13,500 because his employer, a Gloucester vegetable wholesaler, blithely, regularly, and derogatorily referred to him as “Golliwog Brian.” A few years earlier, in 2009, Carol Thatcher, the media personality and daughter of Margaret Thatcher, got into hot water for referring to a French tennis star Jo-Wilfried Tsonga as a golliwog. On the far right, in July 2013 a member of a Welsh white power movement posted a YouTube video of himself symbolically lynching a golliwog as the archetypal symbol of the black Brits to whose presence in “his” nation he was opposed.

Pilgrim and other race issues advocates have an optimistic faith in the power of emerging dialogue. He notes that many people who come to his Michigan museum have never before encountered golliwogs, but express universal condemnation and concern, viewing the dolls as ugly and insulting depictions of black people.

Coverage of Ukip and other groups in the UK is shoving those conversations into the national fore

He hopes these, among other mass exposures to the trope, will create conversation and overwhelming opinion with the power to enlighten collectors as to the harm their habit can cause others. “I know this sounds trite,” he says, “but I speak as an educator who believes in the triumph of dialogue. Many people are uncomfortable discussing race relations in places where their ideas are challenged, but we must have sustained, intelligent dialogue about race relations.” We need, he believes, to just find new language, modes, and venues to have these conversations. Meanwhile, more simply, Grebby hopes that, as he says, “Once people are made aware that black people find the things they do offensive, they’ll start to change their behaviors.”

Coverage of Ukip and other groups in the UK is shoving those conversations right into the national fore. The problem is that golliwog collectors seem more inclined to hedge themselves off, refusing dialogue with what they see as an aggressive, abusive, and hazy and illogical movement. “I did used to get the odd abusive e-mail,” says Wood, “but [I] just blocked them.” Jodi brushes off critics as well, saying, “Not everyone will agree with you and that’s just why the world is such an exciting place to live. I don’t believe in collecting animal heads to hang on walls. I don’t abuse or slander the people that do. That’s their choice and what they find beautiful.” Wood and Jodi, like others, pick up on the knee-jerk reaction of campaigns like the one to eliminate the Alice and Wonderland mural in Scotland, which Grebby admits was a silly case, which made it seem like race rights activists were interested in white-washing history rather than contextualizing and teaching around artifacts of a very real past. It’s easy in such a reactionary environment for the collectors of golliwogs to catch onto weak threads of argument and deny the legitimacy of critiques against their hobby.

When all else fails, though, collectors, in true English fashion, simply run away from controversy rather than face conflict. Many makers and collectors now refer to their products as gollies to escape the derogatory tone and search engine return power of the –wog suffix. The University of Bolton went so far as to try to redirect blame away from the dolls towards another target by claiming that –wog comes from a separate ethnic term, unrelated to blacks, thus absolving the dolls of racism against that group of peoples. If tracked down and confronted, though, individuals like Barnett and Wood have taken to the tactic of holing up and simply ignoring all critiques.

None of this is likely to change anytime soon. Although Ukip’s rise has prompted some uncomfortable yet necessary debate on identity, it doesn’t appear to be changing the tenor, tempo, or haphazard pattern of conversations on race. And if the American example is any guide, no matter how far broad, general racial awareness makes it into national consciousness, it’s fairly easy for individuals and communities to keep aloof and for tropes to remain an unquestioned fixture of life and memory. In the case of the golliwog, a climate of critique may erase it from public life completely. But the minds of collectors will likely go unchanged. And the image of the golliwog will perpetuate itself eternally, popping up now and then in a court case, shop dispute, or political debate to remind people of what lurks just below the surface of society.