Musician Gruff Rhys traces an ancestor’s quixotic journey through America in search of a lost Welsh-speaking tribe.

[Reprinted by arrangement with Hamish Hamilton, an imprint of Penguin Random House, from American Interior by Gruff Rhys. Copyright © Gruff Rhys.]

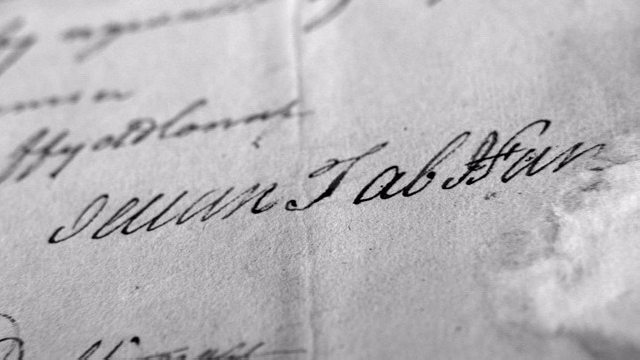

In 1792 John Evans, a 22-year-old farmhand and weaver from the village of Waunfawr in the mountains of Snowdonia, Wales, responded to a plea from the great Welsh cultural mischief-maker Iolo Morganwg to settle, for once and for all time, the quandary of whether there was indeed a tribe of Welsh-speaking Native Americans still walking the Great Plains, descendants of Prince Madog, who was widely believed (especially by Welsh historical revisionists) to have discovered America in 1170. With the aid of a loan from a gullible friend, Evans set sail to Baltimore to begin the greatest of adventures, whereupon he set off on foot and disappeared into the Allegheny Mountains with one dollar and seventy-five cents to his name, in search of the lost tribe. Wales, a rocky peninsular outcrop sticking out of the west of England into the Irish Sea, was the last refuge of the Brythonic ‘Welsh’ people, who had once roamed throughout the British Isle – but by the sixteenth century had been pummelled remorselessly by the emerging English crown, ever since the Romans had left.

It was out of this depressing vacuum that the legend of Madog emerged. From a cynical perspective, Prince Madog was a most useful invention, based on a thirteenth-century romantic saga, ‘Madoc’, concerning a Welsh seafarer of Viking blood, from the pen of the Flemish bard ‘Willem’, best known for ‘Reynard the Fox’. It was Dr John Dee, a mystic of Welsh descent (and from a republican stand-point, the Goebbels to Queen Elizabeth I’s Hitler), who presented Madog as a historical figure – taking liberties with a post-Columbus Welsh take on the Madog story by his contemporary Humphrey Llwyd. As the great colonial powers of Europe began to cast their greedy nets towards the Americas, Dee realized that if he could prove that the medieval Welsh had already settled there it would give a Brythonic monarch a moral claim to those lands, which were already being snapped up rapidly by the Spanish.

Thus, on 3 October 1580, Madog flapped and stumbled like an ill-prepared penguin into the history books. Dee, having upgraded and rebranded the jurisdiction of the English crown to what he now called the British empire, had prepared a warrant for Elizabeth, along with a map that claimed virtually the whole of North America in her name, on the basis that ‘The Lorde Madoc, sonne to Owen Gwynedd, Prince of Northwales, led a colonie and inhabited in Terra Florida or thereabowts.’ In the last decade of the eighteenth century a new Wales was emerging. Out of the shackles of centuries of serfdom and subordination to the gentry, the Industrial Revolution was unfolding, in tandem with radical new ideas concerning the freedoms and rights of the oppressed. A Teutonic Protestant Reformation was used as an excuse to shun the Church of England. The Welsh language, still spoken throughout Wales, was about to enter a period of renaissance as a written language, pioneered by a new elite of exiled and cultured London-based Welsh who now claimed Madog as their own conquistador.

Their imaginations danced to the fantastical prose of one man, a noble savage from the Vale of Glamorgan, a man who dared rescue Wales from a dire Puritan death and who spun its people into a Druidic frenzy. This man was Iolo Morganwg. He promised to travel to the New World to find the Madogwys and bring forth a new age of Welsh empire, and soon the poor farmhand John Evans would be plucked from obscurity to fulfil this impossible task. Having undertaken the task of following Evans’s journey by means of an investigative concert tour, I’d like to say here that all roads seem to lead back to my father, Ioan. During the reorganisation of local government in 1974 the ancient realm of Gwynedd in North Wales was revived in name, and with ambitions to serve the land of Madog, my father really hit the jackpot – with a civil service post at Gwynedd County Council. Moving from South Wales, where his ancestors were steelworkers, innkeepers and preachers, Ioan and my mother, Margaret – a teacher with a sideline in poetry – settled my brother Dafydd, sister Non and me in the Welsh-speaking slate-quarry town of Bethesda, where we grew up, firmly protected by the colossal mountains of Snowdonia. My father was a straight-talking, principled public servant and a dependable man, although further evidence points to a romantic streak that lay pretty close to the surface: a great mimic of animal noises, he once bought the original Lassie’s grandson (granddog?) by mail order, and it arrived in a box at Dolgellau station. He called him Cafall, and the wise collie was his companion on mountain hikes, hypothetically ready to solve any crime mystery that would cross their path. My father was the subject of an MI6 file, as he was branded a Soviet sympathizer whilst a student at Harlech College, and in later life he taught himself German with a Swiss accent.

My father used to tell me that, apart from me and my siblings, he and his cousin Mary Fôn were Evans’s only living relatives – or maybe I misinterpreted him as a child, as from what I’ve since figured out, this isn’t strictly true. I now know of a few others, and there must be descendants of his siblings dotted around the place; if they’re anything like John, they could be anywhere. My father had started, in his spare time, to write books: Welsh-language guides on climbing the Welsh mountains; memoirs of his travels to various mountain ranges; a philosophical book on local governance, which somehow became a textbook at the University of Zambia; and eventually a greatest-hits package, Bylchau (which translates as ‘gaps’, ‘passes’ or even ‘spaces’), which combined his love of mountains and his proto-anarchist political sympathies in one tome. He argued that the spaces between the mountains, the passes and the gaps where people and cultures meet, were more important and more interesting than the summits, the supposed pinnacles. He was in the process of writing a lecture about Evans when he died, and had petitioned the governor of North Dakota with impassioned letters to get some recognition for his relative – a plaque in the Peace Garden State, at least, for Evans’s stunts. Alas, to no avail, although in 1999 they did put up a beautiful slate memorial in Waunfawr. Meanwhile, my brother Dafydd took up the cause in the field of education and wrote two academic papers connected to Evans’s influence on present-day American geography and the political similarities between European and North American minority languages. I therefore grew up fantasizing that I was a direct descendant of John Evans and that his achievements and adventures were not only real but widely known by the general public.

Did these tales have any basis in reality, however, or were they just elaborate bedtime stories? Now, as an adult, I began my journey of verification. One of Evans’s most important historical legacies is the most unlikely consequence of his search for the Welsh-speaking tribe: his emergence as one of the most significant cartographers of the American West. Just as his body was degenerating into the swamp earth, his maps and notes were being copied out of the notebooks and the journals of the Missouri Company and assuming a new life, passed around and then leaked into the hands of Henry Harrison, the governor of Indiana, who in turn passed them on to Thomas Jefferson, the US president, who in turn gave them to William Clark of Lewis and Clark fame. Another copy of his map was passed on to Jefferson directly by Daniel Clark, who was in effect a US mole in New Orleans and would become its first representative in Washington following the looming US takeover. Upon announcing Evans’s death to Samuel Jones, Daniel Clark had written: ‘I believe he was possessed of no other property than his Books and Maps of the country which he had surveyed; these latter will naturally remain for the use of the [Spanish] Government.’

Jefferson claimed Welsh ancestry through his father’s family, who are believed to have originated in Llanberis around five miles as the crow flies from John Evans’s home village of Waunfawr. He was aware of the Madog myth, and instructed Lewis and Clark to keep an open ear for any information in this regard during their famous journey. By the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 the revolutionary country so beloved to John Evans finally occupied the lands where he was buried and whose rivers he had charted. Iolo Morganwg had written in a letter of recommendation for his emissary, ‘our little party are of those who were originally in the opinion of our government rebelliously partial to the Americans, and in America we intend to end our days’.

Find more on Gruff Rhys’ book, album, film and “investigative concert tour” at american-interior.com or through the American Interior app.