As many countries in the West are growing more accepting of homosexuality, why is the Pearl of Africa moving in the opposite direction?

A lot has been said and written about Uganda’s anti-homosexuality law, signed into effect in February 2014. But it seems only few have asked the question: why now? Why, as many countries in the West are growing more accepting of homosexuality, is the Pearl of Africa moving in the opposite direction? Photographer Lee Price was intrigued. He had spent time exploring the underground world of gay cruising areas and bathhouses in the UK, places that are a by-product of the shame still associated with homosexuality in his home country. After publishing a book called “Sex With Strangers,” he applied to the IdeasTap and Magnum Photos Photographic Award with the idea of traveling to Uganda. He won the grant, which he used to spend six weeks there and produce “Against the Order of Nature.” He spoke to R&K from his home in Manchester.

Roads & Kingdoms: What were your first impressions of Uganda?

Lee Price: I had done a lot of research about the situation, read articles, and I expected it to be incredibly hostile. I thought no one would want to talk to me because of the subject matter and no one would trust me. Those expectations were met. It was hostile and it was difficult to find people to talk to. I had never been out of Europe before this trip and it was a bit of a culture shock. It’s a completely different world out there, people do things differently. I had to spend time getting to grips with cultural differences, etiquette, and it was a bit of a learning curve but I soon got into it. Six weeks was plenty of time to get that done and get some decent work. Although having said that, I wish I had stayed a little bit longer.

R&K: The final stage of the competition was judged on the submission of a dream project. Why was yours to travel to Uganda?

Price: Being gay myself, it’s quite close to my heart and it means a lot to me to discuss this kind of issue. But it’s not just that. I think it’s the right time for this kind of project because Uganda seems to be going in the opposite direction from the rest of the world in terms of its attitude towards homosexuality. And they just introduced this new bill, which brings harsher penalties to homosexuality.

I WAS SURROUNDED BY THESE PEOPLE WHO WOULD PROBABLY KILL ME IF THEY ACTUALLY KNEW WHO I WAS

R&K: You mention it’s a hostile environment… How did you approach people on the ground?

Price: I tried to make contact before I went there, so I emailed a few LGBTI organizations. To be honest, most weren’t happy to talk to me until I got to Uganda and I could talk to them face to face. It was an issue with trust. They couldn’t be certain about who I was and my intentions, so it was difficult to do anything before I even went. When I got there, I met with a few organizations and their leaders and made contacts through them. I asked them to put me in touch with people who might be of interest and who could share stories. I mostly met with victims. I did also go to an anti-gay march, which was obviously full of people from the opposite camp, people doing the damage. That was really interesting. And I met other people, people who weren’t gay—for example Bishop Christopher, who’s not gay himself but is completely accepting of it. He was an example of someone who spoke out against all these hate crimes.

R&K: How did you gain the trust of these victims? Was it your idea not to photograph their faces?

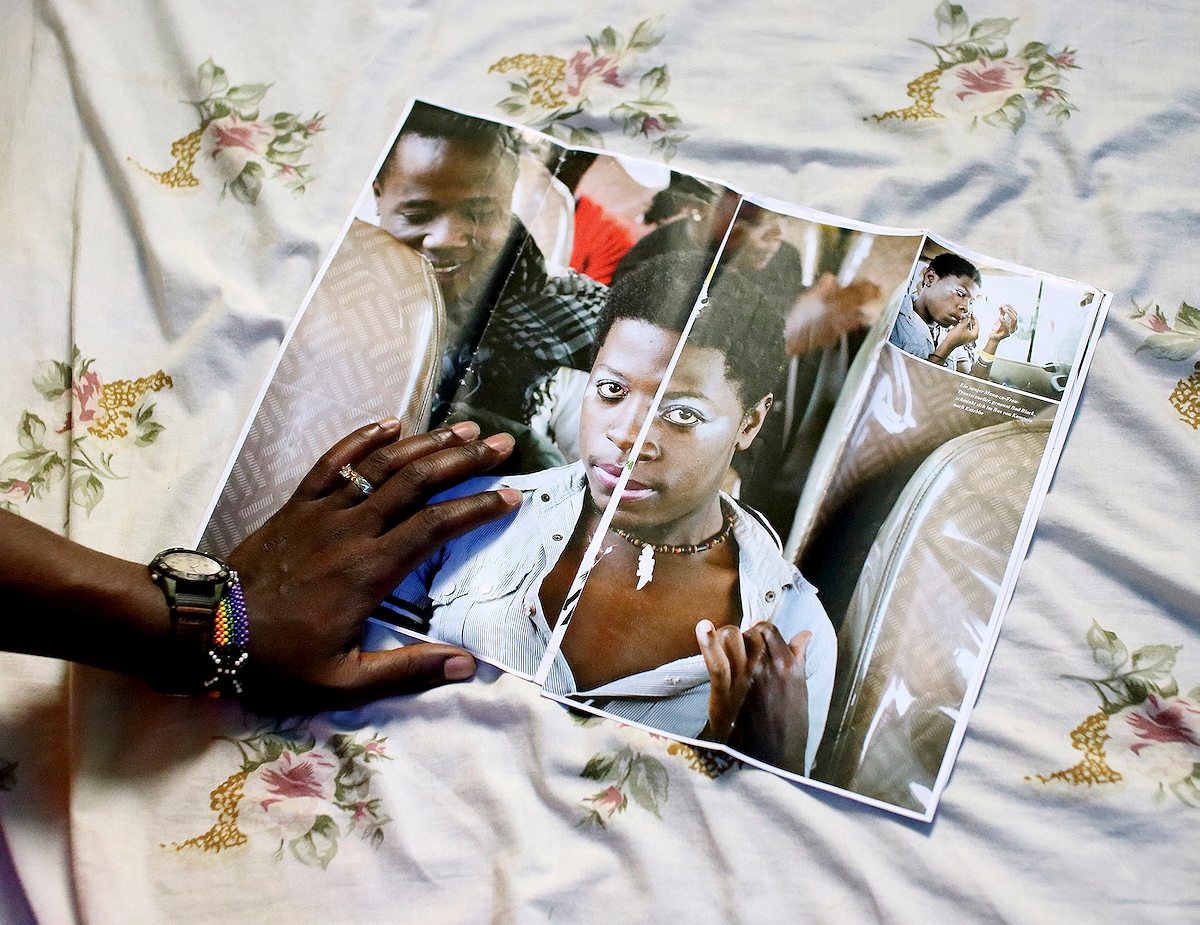

Price: I think the fact that I’m gay certainly helped in persuading them to take part. And I was quite open about that. I was careful about not shooting faces because some people who had been to Uganda to shoot similar stories had been a bit careless. They had photographed faces and these photos had been used against them. There was a Canadian photographer who was there just before me and he did portrait-type work and wrote stories about these people and then the Red Pepper, which is quite a big, influential newspaper in Uganda, got a hold of these photos and printed them, using them to out some people and to cause them harm. So I had to be careful not to make the same mistake because I couldn’t have that on my conscience. For their sake and for mine, I had to work around that.

R&K: The role of the press in disseminating hate towards homosexuals seems huge. Why do you think that is?

Price: Yes it is. I mean, most Ugandans are homophobic, so it’s no surprise that the press reflects that. It’s what people are interested in right now. People actually agree with this new law. A headline like: “Exposed: 100 Top Homos Outed!” helps to sell papers. People actually want to know this kind of stuff, so it isn’t surprising that the media has grabbed onto it. They publish addresses, they publish places of work, they publish photos… They’re just ruthless and they have no conscience I suppose. It’s hard to walk down the street and see that stuff plastered on the front pages of newspapers because it’s just so different to what you’d find here. It just wouldn’t happen here. And to see that this was actually the norm there was quite a culture shock. That was one of the things that hit me hard, the way that the media has that influence and that they’re just so blatant with it.

IT’S HOMOPHOBIA THAT WAS IMPORTED, NOT HOMOSEXUALITY

R&K: What was it like for you personally to report this story?

Price: I wasn’t really hurt by the things that I saw or heard because I was well-prepared and I was expecting that kind of thing. At the anti-gay march, it was a little hard to keep smiling the entire day as I was surrounded by these people who would probably kill me if they actually knew who I was and what I stood for. But I didn’t really feel unsafe at any point. Pastor Martin Ssempa, who was fronting the rally, confronted me at one point and asked if I was gay, taking a copy of my passport… That was probably the scariest moment, but even then I knew that he couldn’t really do much other than put me in prison, which would be pretty shit but I wasn’t overly frightened. I think getting that work done meant more than the any kind of fear that I had.

R&K: But this wave of homophobia is fairly new, isn’t it?

Price: It is new. Well, it’s come in two waves really. When the British colonized Uganda, we brought homophobia along with the Bible. Before that, the king of Uganda was actually gay himself, so it was fairly accepted in the country and in Africa in general. And then we came along and changed things. But more recently, homophobia has had a second wind because Christian conservatives from the U.S. have gone over—one guy called Scott Lively in particular, who fronted this movement—with the intention to cause damage and stir things up. They were having a hard battle at home where obviously things are becoming more accepted, so I think they wanted an area of the world where their voices would be accepted and where they would have more influence. That really kicked things off. They spread rumors about recruitment of children by homosexuals, and that really scares people. Altogether, the movement by these evangelicals sparked the anti-homosexual bill. It’s no coincidence that the year after Scott Lively and his team went over there, the bill was put into process. So like you say, it hasn’t always been like this, but it’s getting worse, which is the scary thing.

R&K: From what I’ve read, it also looks like many Ugandans blame foreigners for bringing homosexuality in their country…

Price: Yes, that’s the interesting part. Ugandans are adamant that homosexuality is an import from the Western world. And that’s interesting because it’s actually the opposite‑it’s homophobia that was imported, not homosexuality.

R&K: The Western press and politicians have been extremely critical of what’s happening to homosexuals in Uganda. You’ve actually been on the ground—do you think their portrayal is accurate?

Price: I expected that every single non-gay person that I met in Uganda would be homophobic. And it wasn’t entirely true. I did meet quite a few people who were accepting. So I think the West is slightly exaggerating, but there is an awful lot of hostility. I did have to make a point of not buying into this bad press because it isn’t their fault at the end of the day. We brought the homophobia, so it would be pretty rich of someone from the West to go and start pointing the finger because they believe what they’ve been taught, and it’s as simple as that. Fifty or sixty years ago, the West was very much the same.

R&K: What do you think the consequences of this crisis can be?

Price: It’s massively damaging. It teaches people that it’s OK to hate someone just for the way that they were born. But I do think that there is hope. I think it can only go one way in the end. It might have to get worse to get better, but with time, we’ll see progress.

You can see more of Lee Price’s work on his website and learn about the IdeasTap and Magnum Photos Photographic Award here.