As Hiroshima remembers its dead, Tokyo envisions new ways to play the shellgame that is modern warmaking.

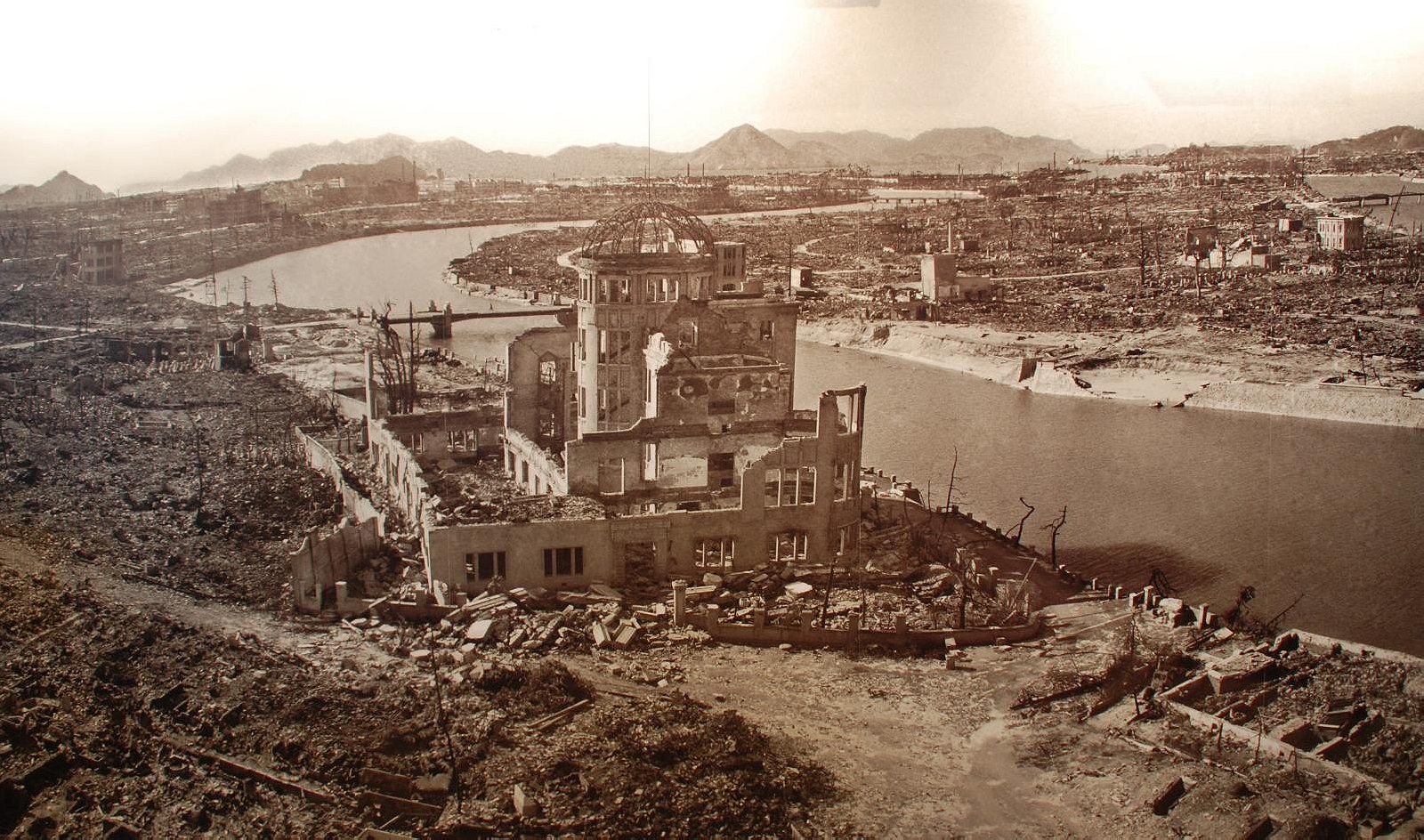

Keiko’s husband is a Buddhist priest, and a day like this—the 69th anniversary of the atomic attack on Hiroshima, when the Americans summoned a circle of hell alongside the Motoyasu River—would seem to call for priests more than politicians. But he is not here. “It is too much of a circus for him,” she says, as she walks along the banks of the river with me. “He thinks it should be a time for prayer.” Instead, the morning’s memorial services were overrun with notabilities in clear rain ponchos who stood solemn and useless as the bell rang at 8:15am to mark the time of detonation.

By the time I arrive later in the evening with Keiko—an old friend from previous trips to Hiroshima—many thousands of visitors and locals are lined on the banks of the river to watch candlelit lanterns float downstream from the hollow Genbaku dome, the iconic ruin of the attack.

About a thousand people are queuing in line in front of the Peace Museum itself to light incense, clank a heavy coin in the alms box, maybe take a cellphone picture of the Genbaku Dome—perfectly framed in the distance by the memorial and its reflecting pool. Along the side of the memorial are dozens of elaborate wreaths from places like the Rotary Club of Hilo, or with personal greetings from the General Secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation.

There’s a brisk business at an upscale ice cream parlor near Hondori. So many of the witnesses are gone—just last month the final surviving member of the Enola Gay crew that dropped the bomb died—and there is a sort of summer nighttime stroll quality to the evening. August is a rare time of leisure in Japan, of summer festivals and lantern parades and fireworks, and tonight in Hiroshima, that culture mixes uneasily with the profound and elegiac.

But what a burden, what a mission, for modern Hiroshima. In a way that Nagasaki never did, Hiroshima has styled itself as the Tragic Reminder that peace is more than a greeting-card abstraction.

This is an important moment for remembering this. Not just because the Peace Museum is more popular than ever, nor because Caroline Kennedy became just the second U.S. ambassador to Japan to come to the commemoration. Rather, it’s because of a scion of another political dynasty who was on-hand at the ceremony, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. His grandfather was a wartime cabinet minister under Tojo, and before that an official in occupied Manchuria. And he, more than any other single person in Japan, seems to be pushing the region toward more war.

Japan’s constitution is unique in the world—its Article 9 says “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.”

That is an extraordinary commitment. And even though it was the victorious Americans who authored the document, Article 9 has turned into a point of genuine pride for many Japanese.

It turns out that “forever” wasn’t all that long, however. Abe, whose last attempt to militarize the constitution cost him his job in his first stint as Prime Minister, succeeding in gutting Article 9 last month. He used a cabinet resolution to claim now that Japan can fight overseas if “countries with close ties” need their assistance, even if Japan itself is not under attack. The change allows Japan full access to the shellgame that is modern warmaking, in which statements of common cause and perceptions of a common threat can bring diverse nations into total war anywhere on earth. Isamu Ueda, a legislator from the New Komeito Party that is part of the ruling coalition, defended the move as part of Japan’s “proactive contribution to peace.” Although Abe has decided not to visit the Yasukuni Shrine this year, he has long built his political career out of trying to restore Japan’s military musculature. This is no different. But Abe’s electorate is not moved. Fewer than a third of respondents in a recent survey approved of the resolution.

Just days before the resolution, a man set himself on fire in Tokyo’s shiny, busy Shinjuku station to protest changing the constitution. But when I arrived there a few days after the Hiroshima anniversary, a ragtag rightwing militia in military gear was staging a very different kind of protest, against Russian control of the so-called “Northern Territories”, the islands north of Hokkaido.

The Chinese are not pleased about any of this. Two days after Abe’s announcement, China’s State Archives began releasing the confessions of 45 Japanese war criminals. To their mind, Japanese militarism has been a constant threat. Japan has made a habit recently of backing the anti-Chinese side of any regional dust-up. And even under a peacetime constitution, Japan already has one of the top ten militaries in the world. More recently, Tokyo ended the formal prohibition on exporting military hardware, paving the way for a renewed military-industrial complex.

An effort is underway to nominate citizen groups who support Article 9 for a Nobel Peace Prize. Winning it could serve, supporters say, as a way to channel Japan’s national pride back toward its best postwar innovation: pacifism. In Tokyo, a friend told me he’s tired of having Japan controlled by the U.S. or, in his mind, South Korea. He supports changing Article 9. But as the last lanterns slip away under the peace bridge in Hiroshima, there is no talk with Keiko or our other friends about the rights of modern Japan. Just a hint of silence, a memory somewhere of unfathomable loss, and a sort of faded hope that it might never happen again.