The subcontinent’s vineyards want to turn India into a South Asian Tuscany, but can wine survive in a land of brown liquor?

NASHAK, India—

Late last month, LVMH—the French luxury conglomerate responsible for Louis Vuitton, Fendi, and Bulgari—threw a major, booze-soaked high fashion event. But instead of the customary champagne-filled soiree in a European castle, LVMH gathered Bollywood’s best to celebrate their subsidiary, famed champagne house Moët & Chandon, in a lavish Mumbai hotel. The unusual occasion—a launch party for their foray into the fledgling world of Indian wine.

Indians rank among the lowest wine consumers in the world. Even though the industry has blossomed in the last decade, growing from six to 50 domestic wineries, persistent social stigmas hamper further progress. Only a third of Indians drinks alcohol; those who do like to stick to harsh, local Indian spirits.

In spite of these challenges, a wine industry thrives on the gentle sloping hills of the Maharashtra region, near the Hindu holy city of Nashik. For centuries, these hillsides have nurtured microclimates with hot days, cool nights, and reliable rainfall ideal for table grapes. But India has only recently tried to cash in on its potential as a South Asian Little Tuscany.

In the shadows of Mumbai’s skyscrapers, workers clocking out from a dairy factory duck into a grungy neighborhood bar. Here, local “whiskey” reigns supreme—distilled from molasses and smelling like varnish, it’s the only thing on tap. Before I can pull up a stool, a toothless man hands me a glass. Soon, nine new friends cluster around, and I bring up the subject of wine. Only one person has ever tried it. He makes a face and says, “Too sour.”

For the enthusiast looking to get serious about Indian wine, the unquestioned first stop is Sula Vineyards. Here in 1993, Rajeev Samant, a Stanford-educated Silicon Valley dropout, returned to his family’s humble estate to explore why the region’s profitable table-grape industry had never expanded to include wine grapes. Six years later, he planted the country’s first sauvignon blanc and chenin blanc grapes. From the paltry initial batch of 1,000 liters, Sula has grown into an empire producing 6 million liters of nearly two-dozen varietals in 2012.

The 35-acre estate has two restaurants, an outdoor bar, and a 32-room resort. I admire Samant’s ambitious effort to try to jump-start wine tourism in India. But as I sit down to dinner at Sula’s Indian restaurant, I watch the two men seated next to me look at the menu perplexed, then order coconut juice. When the waiter informs them that coconut juice is not on the menu, they both order local Indian whiskey instead.

This is the market battle Sula has waged for more than a decade. The best hope for wineries like Sula is to lure some of India’s 300 million whiskey consumers away from the varnish-liquor. But that is no small task: Eight out of the 10 best-selling whiskeys in the world are from India, with most of them only sold domestically.

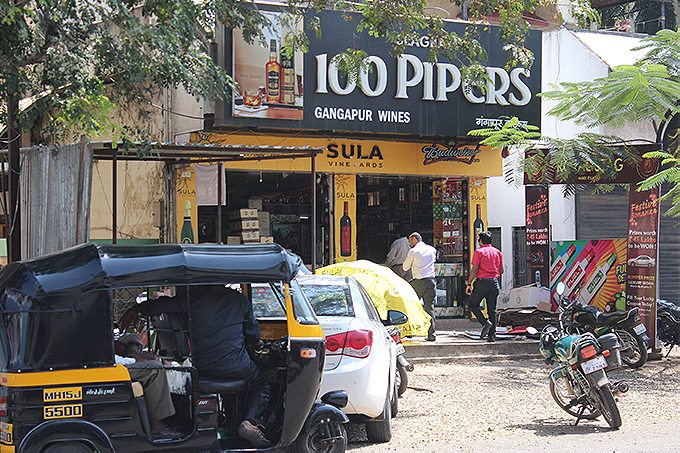

The waiter begrudgingly places the men’s order but not before a bit of gentle ribbing. “Why don’t you walk to a wine shop for that whiskey!” the waiter teases. In working-class restaurants in India, BYO-whatever is customary. The words wine shop in the West might conjure images of sleekly minimal design, but the reality in India is quite different. Wine shops are dusty, government-run affairs that dole out whatever they have in stock—usually some concoction of fermented molasses.

“I’ve heard some wineries talk about increasing the alcohol volume to 20 percent,” Mahajan says. With the Indian liquor market releasing special editions of high-alcohol booze, the wine industry is feeling the pressure to compete. As we leave the tasting room, one sommelier shows us a Marathi meme floating around the Internet. It states that it takes an hour of drinking wine to speak English but only a few minutes of local whiskey to accomplish the same task. “At university, our parties only had whiskey. Maybe only 5 percent of the people knew about wine,” the sommelier laughs. A member of India’s glut of MBA graduates, he hopes to help expand the country’s drinking frontiers.

About 20 miles south, near the serene Mukhne Dam, I meet two young winemakers, Sanket Gawand and Asmita Pol, at Vallonné Vineyards. Founded in 2009, Vallonné produces a fraction of the wine made by other vineyards. “We want to be known as India’s premier boutique winery,” Pol says. With a lower percentage of contract farming than other area wineries, Vallonné is able to keep a more watchful eye on their crop rather than deploy viticulturalists to check on far-flung farms.

A small upstart, Vallonné has the freedom to make bold choices—like experimenting with different oak barrels, a risk for such a small crop. But who is their market?

“My generation. We pursue what we like and what we want,” Gawand smiles.

The youth may be the most promising target for India’s nascent wine industry, but the lingering concern among the homegrown wineries is what effect the introduction of foreign names—like the sparkling wine of Moët & Chandon—will have on domestic production. India’s young people have a huge appetite for luxury products, but it’s unclear whether they like luxury products made in India.

“Chandon might push some wineries out of the market. Or it might make the world finally pay attention to wine in India,” Mahajan says. Moët & Chandon’s sparkling wine launch certainly perked up the local industry—it was no coincidence that one winery released its first brut and Sula re-launched its own sparkling wine with a new blend and new packaging one week prior to the French powerhouse’s splash into the Indian market.

The economic crisis, coupled with a glut of new wineries, wreaked havoc on the industry.

But the market can be fickle. In June 2008, the New York Times ran a glowing article about the rise of Indian wine. But less than a year later, the economic crisis, coupled with a glut of new wineries, wreaked havoc on the industry.

“Growing wine in India is tough, but we think we’re doing it well,” Vallonné’s Gawand insists.

After three days of touring vineyards, Mahajan and I kick back in a dingy hotel restaurant. With no wine or ice in sight, we settle for Indian whiskey. It only takes a couple of tall glasses to catch a buzz, and Mahajan begins gesticulating, wide-eyed about schemes to grow the industry. Grapeseed oil. Tourism. Brandy. What kind of brandy, I ask him skeptically.

“Without a doubt, it will taste better than this,” he grimaces.