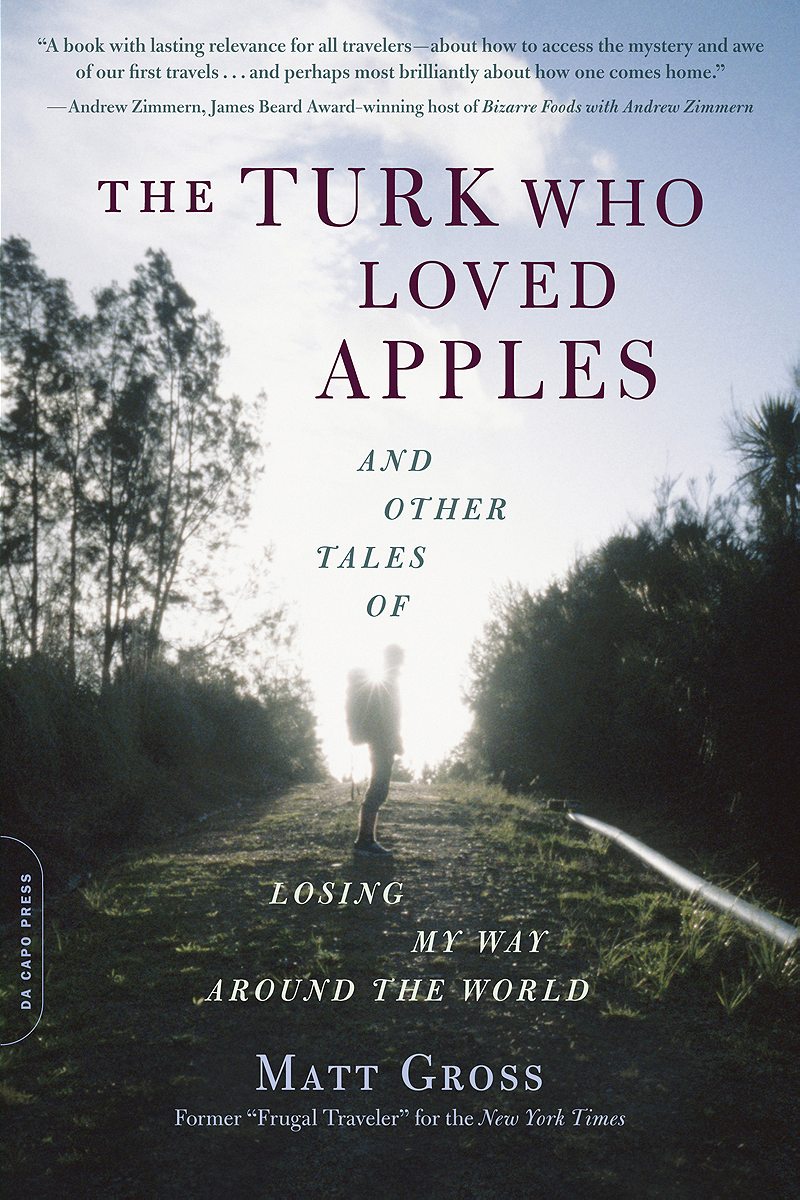

An excerpt from Matt Gross’ The Turk Who Loved Apples.

GERMANY—

“Zimmer frei,” read the hand-painted sign in front of the tidy modern house at the edge of Altenbrak, in the Harz Mountains of central Germany. I’d just emerged from an overgrown trail, having hiked twelve miles from the town of Thale, and the sun was starting to set behind the wooded hills. I recalled the old legends about the Harz—that witches fly around the peak of the 3,747-foot Brocken, and that a creature called the Brocken Spectre roams the misty forests—and in the growing dark they seemed all too plausible. I needed a place to stay. And right there was the zimmer frei, the institution I’d been counting on. Throughout touristed zones of rural Germany, I knew, homeowners with rooms to rent would put up such signs—“room available,” they say—to lure in wanderers such as myself, desperate for a bed but unwilling to pay the thirty euros or more for a pension or a proper hotel. And as the Frugal Traveler for the New York Times, saving money was my raison d’être.

I walked up to the front door, set down my backpack, and rang the doorbell. Nothing. Some lights were on inside, I could see, so I rang again. And again. Finally, a woman opened the door. She was older, large-ish, and thoroughly confused to see me.

After twelve miles that day, what was another five hundred meters?

“Zimmer… frei?” I asked.

Her expression changed to one of understanding. “Nein,” she said in a neutral tone, and closed the door.

Fine, fine. I hoisted my twenty-five-pound bag and walked deeper into town. After twelve miles that day, what was another five hundred meters? If I couldn’t keep my energy up at the end of a trek, I’d never get through the forty-odd miles I’d planned for the rest of the week, following in the footsteps of Goethe and Heine to the top of the Brocken. The walk so far had been perfect, starting out on well-trod paths, branching off on old logging roads, passing through tiny villages of dark-wood vacation homes. I loved the solitude, the jaunty pace of my feet on the ground, the slow accretion of mileage. Slowly but surely, I was making progress—and burning off enough calories that I could eat whatever I liked.

And that first night, once I’d checked into the Zum Harzer Jodlermeister pension and restaurant (I bargained them down from forty-five to thirty-five euros), I indulged indeed: schnitzel, noodles in mushroom cream sauce, apple strudel, vanilla ice cream, and a big pilsner. In bed by 10 p.m., I slept like the dead.

For four days, I ate big German breakfasts—rolls and cold cuts and cheeses and butter and jam, hard-boiled eggs, maybe some yogurt, buckets of weak coffee—and set off early in the general direction of the Brocken. I’d tramp for hours, sometimes through small, populated towns, more often through places that were no longer quite as wild as they’d once been. The logging routes led into patches of regrown forest, and more than once I found myself backtracking around lakes and over streams. The way forward was never obvious, and I covered more ground than I should have.

As I popped berry after berry, I remembered childhood summers in Amherst

Though I never knew exactly where I was going to be, at lunchtime I always managed to pass through a town or village, where I’d pick up a hearty, rustic lunch of bread, cheese, ham, and maybe an apple. Once, at a traditional charcoal-making plant, I got a bottle of schwarzbier, a kind of black lager, and another day, just east of the former East Germany–West Germany border, I happened on Kukki’s Erbsensuppe, a roadside stand selling bowls of thick split-pea soup with bacon that had opened just after reunification. Eating like this was perfect; when food was fuel I didn’t have to think long or hard about what I was devouring, as I would for a story in, say, Paris or San Francisco, but it didn’t hurt that it was all delicious.

Of everything I ate in the mountains, nothing was as gratifying as the wild raspberries and blueberries that grew alongside the paths. Whenever I’d spot the bright red or pale blue fruits, I’d hurry over and quickly strip them from their bushes, shoving great handfuls into my mouth. Each one was like a sharp pinprick of sweet flavor, intense and pure, and as far as I could tell this great buffet stretched across the region. As I popped berry after berry, I remembered childhood summers in Amherst, where my brother, my sister, and I would pluck blackberries from the backyard and sit on the porch consuming them, our fingers and lips stained dark with juice. Free fruit, unplanted by human hands, had always seemed to me one of nature’s greatest gifts, and by my efforts I hoped to become worthy of her generosity.

A few days later, however, when my Harz Mountains story appeared on the New York Times Web site, I found a disturbing notice in the comments section. “I know all those raspberry and blueberry bushes throughout the forest look tempting, but most Germans wouldn’t dare to eat them,” wrote someone named Robyn. “The reason being the fuchsbandwurm a type of parasite that the foxes leave in the forest, contaminating all those lovely, free berries.”

Fuchsbandwurm? I turned to Google and Wikipedia: The “fox tapeworm” (Echinococcus multilocularis) is a parasite carried in the intestines of foxes, and often dogs, in China, Siberia, Alaska, and central and southwestern Germany. The foxes, which eat berries, can contaminate the plants they touch, and when humans contract the disease, it attacks the liver like a cancer. It is, says Wikipedia, “highly lethal.” Treatment is surgery followed by various forms of chemotherapy, but complete cures appear to be rare. Worse, the parasite has a long incubation period—ten or even twenty years—and is difficult to diagnose.

At least with giardia, I came to know my tormentor

Even now, years after that hike across the Harz, my heart beats faster and my stomach turns as I contemplate what may befall me in another six to sixteen years. Worms may dissolve my liver, and there may be no hope. Of course, Louis Morledge, my travel doctor in New York, tells me not to worry; my liver tests have been fine so far. And I did generally—but not exclusively—eat berries from at least waist height, where foxes’ fur wouldn’t brush. And Klaus Brehm, a fuchsbandwurm specialist at the University of Würzburg, has reportedly said the idea “that one could get the fox tapeworm from berries belongs in the realm of legends.” And my friend Christoph Geissler, another German doctor I met randomly on a shared taxi in Israel, giddily confessed to eating wild berries all the time, everywhere, regardless of the fuchsbandwurm risk. And, and, and…

And yet I feel terror. At least with giardia, I came to know my tormentor, to understand its causes and symptoms and cures, and to make a kind of peace with it. With the fox tapeworm, there can be no such rapprochement. If I have it, I will kill it—or it will kill me. And if the latter comes to pass, I will have no hand to blame but my own. But I hope, in those fucking miserable final moments a couple of decades from now (maybe), the berries—and everything else—will have been worth it.

[Header image: “Wild berries” by Mike Babcock, used under CC BY 2.0.]