SB Tang braves the wrath of one of Penang’s most controversial hawkers to eat a Malaysian street-food masterpiece.

In Penang, there is a legend of a lady hawker whose char koay teow (Hokkien for “stir fried flat rice noodles”) is as delicious as her manners are curt. Serious eaters talk about her in tones of hushed reverence. They say that her char koay teow is so good that she can afford to tell prospective customers “cannot wait then don’t eat!” Other, less serious eaters call her “the eyebrow-tattooed bitch”. I am here to taste the legend—the finest specimen of the dish which stands first among many in the pantheon of Malaysian street foods.

Her hawker stall, based at Heng Huat coffee shop in Lorong Selamat (lorong is the Malay word for “lane”), is colloquially referred to by locals as “Lorong Selamat char koay teow”. Having grown up in Australia in the ’90s when Seinfeld was in its prime, I can’t help but refer to her as “the Char Koay Teow Nazi”—an effusive compliment on the delectability of her food and the seriousness of her craft, rather than a comment on her political beliefs.

This purveyor of umami (her real name is Soon Suan Choo) is famed for her fire-engine red hair net, irresistible food and premium pricing: a large plate of her char koay teow with all the trimmings will set you back RM9.50 ($2.89 at the current exchange rate)—approximately three times the average Penang hawker price—in a country where the real average monthly wage is a mere RM1,851 (roughly $563) compared with $2,970 in the US.

But Ms. Soon is perhaps most famous for her brusque manner and strict ordering rules. In 2010, she became the target of a concerted boycott campaign. An email did the rounds, supported by a cartoon of the now infamous incident whereby she allegedly barked at a little old lady: “My koay teow very expensive! People like you can’t afford!” As of publication, a “Banned Lorong Selamat Char Koay Teow” Facebook page has 1,073 likes.

In a country where eating only narrowly shades watching English Premier League football on TV as the national pastime, Penang, an island off the north-western coast of peninsular Malaysia, is acclaimed above all other destinations for its food.

Originally called Pulau Pinang in Malay—literally “Isle of the Betel Nut” in reference to the betel nut palms which were abundant on the island—Penang was contractually acquired by Captain Francis Light on behalf of the British East India Company in 1786 from the Sultan of Kedah in exchange for the supply of arms and ammunition, and was the British Empire’s first major commercial and naval foothold in a region which it would soon come to dominate. Captain Light christened the capital George Town.

Sparsely populated at the time of its acquisition by the British, Penang developed into a busy commercial centre and a cultural and ethnic melting pot in the centuries that followed under British rule. The British, the Chinese, Indians, Eurasians and Malays—all came to Penang and all (yes, even the British) brought with them their food.

EVEN THE HUMBLE PIECE OF TOAST HAS BEEN TRANSFORMED BEYOND RECOGNITION

So it was that Penang developed true, unaffected fusion food decades before “fusion cuisine” became the latest culinary buzz phrase. Take, for example, one of Penang’s signature dishes, known throughout the rest of Malaysia as asam laksa, but referred to in Penang as simply laksa, which deftly combines staples of Chinese cuisine such as rice noodles, bean sprouts and soy sauce with Indian turmeric and Malay belacan (dried shrimp paste), as well as local Southeast Asian fruits (pineapple) and herbs (ginger flower, lemongrass and shallots). Even the humble piece of toast has been transformed beyond recognition by its marriage to kaya, a jam made from coconut milk, eggs, pandan leaves and sugar.

The fusion of cultures found in Penang’s food is equally evident in George Town’s architecture. Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion—named after the man who built it in the early years of the 20th century, a Chinese tycoon dubbed the Rockefeller of the East—is a uniquely eclectic combination of Chinese, English, Scottish and Malay architectural influences. Suffolk House is an Anglo-Indian colonial masterpiece, described by no less an authority than Lord Minto, the then Governor-General of India, after a visit in 1811, as “one of the handsomest [houses] … in India”. (Back then, Penang was a Presidency of India.)

Little wonder then that in 2008, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee added George Town and Malacca, Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca, to the World Heritage List, stating that they “reflect the coming together of cultural elements from the Malay Archipelago, India and China with those of Europe, to create a unique architecture, culture and townscape.”

My Mum was born and raised in Penang. As were her two sisters, brother, father and mother. Ever since I was a boy, I’ve loved going back there for family holidays. I’d like to say that that was because of some deep, profound connection with any ancestors. But that’d be a lie. In truth, it was always about the food.

Over the years, I’ve invested countless calories exploring the delicate balance of laksas, the cosseting comfort of curry mees, the textural delights of ban chan kuihs and the elegant simplicity of wan tan mees.

The location of my grandmother’s house was marked not by a number, street or suburb, but by the roadside residence of my favourite wan tan mee hawker in the morning and my favourite ban chan kuih hawker in the afternoon. If I was ever in any doubt, all I had to do was keep an eye out for one of my portlier cousins who wiled away his afternoons by surgically attaching himself to the ban chan kuih hawker’s cart and hoovering up the warm pancakes the hawker kindly gave his number one fan.

On this particular day, though, I am in George Town with my family for one reason alone: to eat Ms. Soon’s controversial char koay teow. We arrive at her hawker stall at around noon—just in time for rush hour. The kopitiam (the local word for “coffee shop”, a portmanteau of the Malay word for “coffee”, kopi, and the Hokkien word for “shop”, tiam) at which her stall is based is a typically Malaysian affair. The high-ceilinged, open-air shop occupies the ground floor of a two-storey building. The full-width folding doors are thrown open, allowing the heavy tropical air to circulate and the waiters easy access to the ground floor veranda crammed with tables. The place is, as usual, overflowing with customers.

Upon our arrival, the first thing I hear is Ms. Soon saying loudly in Hokkien (the dominant Chinese dialect in Penang): “Europeans do not know how to eat char koay teow.” I peer into the back of the kopitiam and notice a solitary Caucasian male dining with a female Asian companion. I assume that he’s made the mistake of ordering himself rather than letting his local-looking companion do so. I hope for his sake that Ms. Soon deigned to fulfill his order with the real thing, rather than some hastily-assembled, watered-down substitute.

I ASSUME SHE WOULD ACCEPT THE USE OF TWO ENGLISH WORDS TO PLACE AN ORDER. I AM WRONG

Being the eldest of three brothers, I take it upon myself to place our order. I saunter up to Ms Soon’s stall, pausing only briefly to inhale the intoxicating fumes rising from her wok—it is the smell of the elusive “breath of the wok” prized by Chinese gourmands since time immemorial. I utter five words to place my order: “four char koay teows please.” I assume that, like most hawkers on an island where basic English is widely-spoken, she would accept the use of two English words to place an order.

I am wrong.

Her reply comes in Hokkien: “Do not speak to me in English.”

Problem: my Hokkien, acquired through a lifetime of exposure to scurrilous family gossip uttered by aunties in my presence, does not extend to numbers. So whilst I am perfectly capable of understanding and translating the bulk of a parent’s complaints about their children in Hokkien (an enduringly popular conversation topic in Penang kopitiams), I haven’t the faintest clue what the Hokkien word for “four” is.

I pause momentarily to take stock (and leisurely enjoy more than a few deep gulps of the wok’s aroma). I briefly contemplate the prospect of lunch without her char koay teow, before deciding to initiate plan B: let my Dad order.

It turns out that Ms. Soon’s customers are required to follow an unwritten but strictly enforced ordering procedure. The account which follows is a mere induction based on my own empirical observations.

As a general rule, all communication must take place in clear and loud Hokkien. If you cannot speak Hokkien, ask a friendly local to place your order for you. Enter the kopitiam and secure a table. Note your table number—you will need this later. Approach the stall and state your order, remembering to specify what size plate and which, if any, of the optional extras you would like. She will then advise you of the approximate waiting time and ask you whether you are willing to wait. Say “yes”. She will then ask you for your table number. State your table number; if you do not have one, your order will be declined. Return to your table and commence waiting for your food.

My Dad, fluent in four Chinese dialects, experiences no problems following her ordering procedure. He returns to our table and tells us that she has informed him that it will be a 45-minute wait for our four large servings of char koay teow. Better still, he has managed to place our order just before the height of rush hour.

I sit back and wait.

Newly arrived pilgrims to this smoky altar to street food are informed that they will have to wait an hour to receive their food. They all happily agree to do so. Whatever Ms Soon’s faults may be, dishonesty is clearly not one of them—she is upfront with all her customers about both her premium pricing and the lengthy waiting times for her product. Still, the people pour in.

THERE, LAID BARE IN BROAD DAYLIGHT, IS THE SECRET TO HER SUCCESS: CHARCOAL

I watch as Ms. Soon constantly feeds more charcoal into her stove. There, laid bare in broad daylight, is the prosaic secret behind much of her success: unlike the vast majority of her contemporaries throughout Malaysia and Singapore, she has stuck with the old-fashioned charcoal fire rather than switching to modern, easy to maintain gas flames. The charcoal aroma imbues her char koay teow with an extra layer of flavor and the higher wok temperature unlocks tastes and textures gas-powered woks simply can’t achieve. Of course, such improvement comes at a price which not everyone is willing to pay: charcoal fires require constant, laborious manual feeding. Ms. Soon is one of the few left who are willing to pay that price. That is why she is one of the few hawkers still able to create the breath of the wok.

After my Dad orders, a distinguished-looking lady approaches the Ms. Soon’s stall. She is ethnically Chinese, elegantly dressed and impeccably coiffed. She attempts to order in fluent English. She receives the same response from the temperamental cook that I got earlier.

But the distinguished-looking lady repeats her attempts to order in English. She must be Singaporean, I think to myself (nowadays, most Singaporeans cannot speak Hokkien). Her subsequent ordering attempts meet with no response from Ms. Soon. The distinguished-looking lady is reduced to standing in front of the stall, perplexed and flustered. My Dad gets up to go help her but a local beats him to it, placing her order for her in Hokkien.

EATING A PLATE OF CHAR KOAY TEOW THIS GOOD IS A WIDE-RANGING SENSORY EXPERIENCE

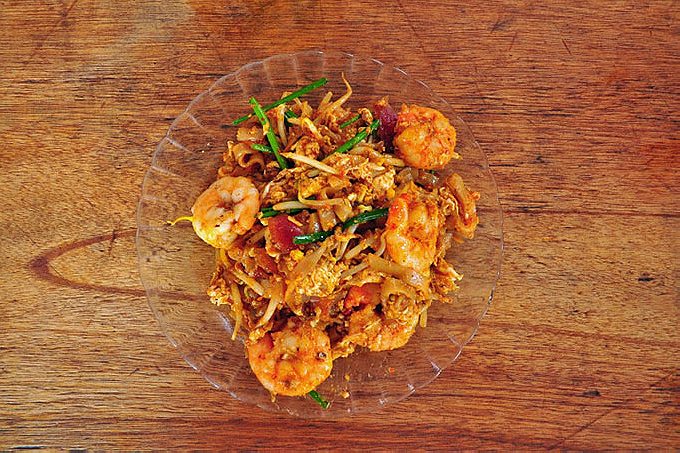

Thirty minutes after my Dad places our order, our food arrives. Eating a plate of char koay teow this good is a wide-ranging sensory experience: even before it arrives, my ears are filled with the crisp, sizzling sound of a well-fed, charcoal-fired wok at work. When it lands on the table, the first thing that hits me is the divine fragrance—I bow my head and let it wash over me.

Only then do I actually lay my eyes on the dish. The thin, luminescent noodles glisten in the bright afternoon light, but—unlike so many examples of char koay teow found outside Penang made with wide noodles—they are neither gluey nor greasy. Crucially, the noodles are visibly charred at the edges without being burnt. Like all proper Penang-style char koay teows, the dish is an appetising light brown in colour, not the ink-cartridge black of the char koay teows typically found in the rest of Malaysia and Singapore.

Then there is the taste. The many disparate flavors—the sweetness of the prawns and cockles, the richness of the Chinese sausage and pork lard, the bite of the chives and chilies—are seamlessly fused together by the breath of the wok, creating something new and whole and infinitely greater than the sum of its parts. Before long, the dish is gone; lost in the ephemeral pleasure of the moment, I have devoured the char koay teow almost without realising it. And I am left craving more.

Now, if only I knew the Hokkien phrase for “seconds please”.