An Israeli photographer visits the prisons of Ukraine and Russia.

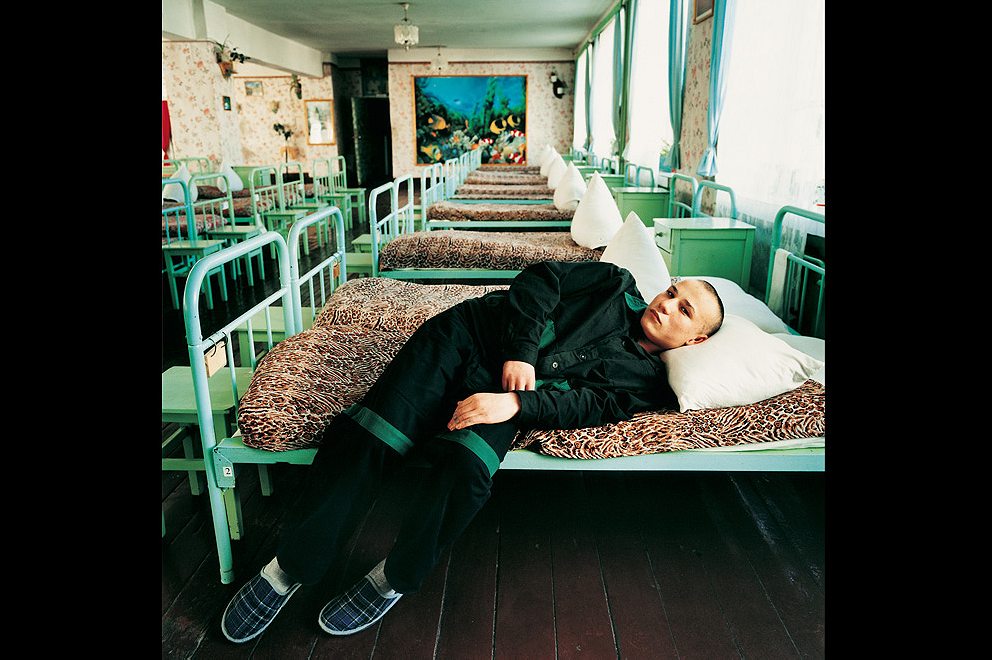

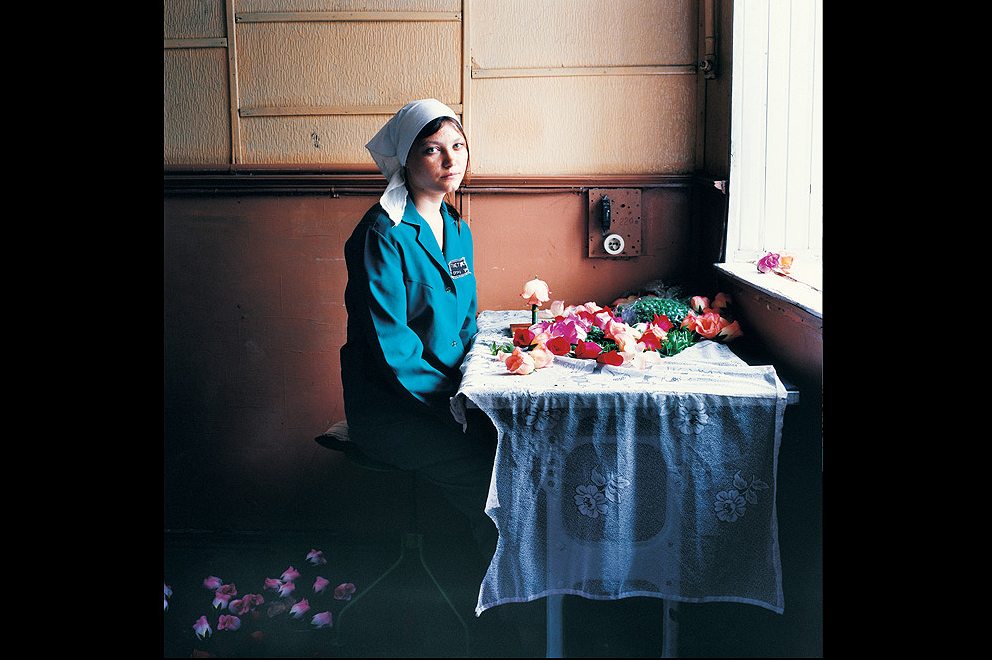

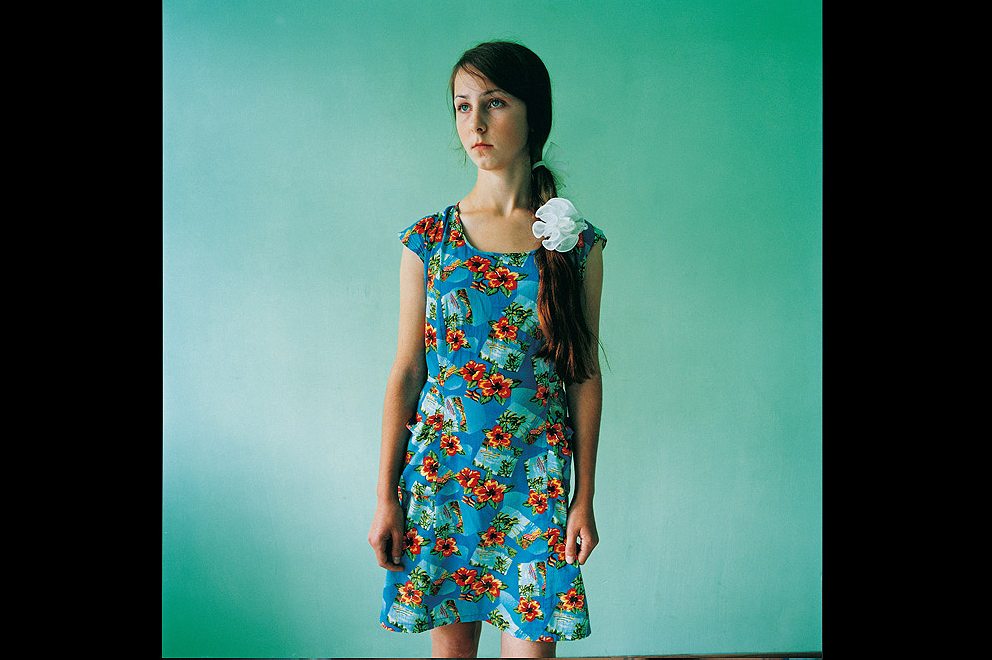

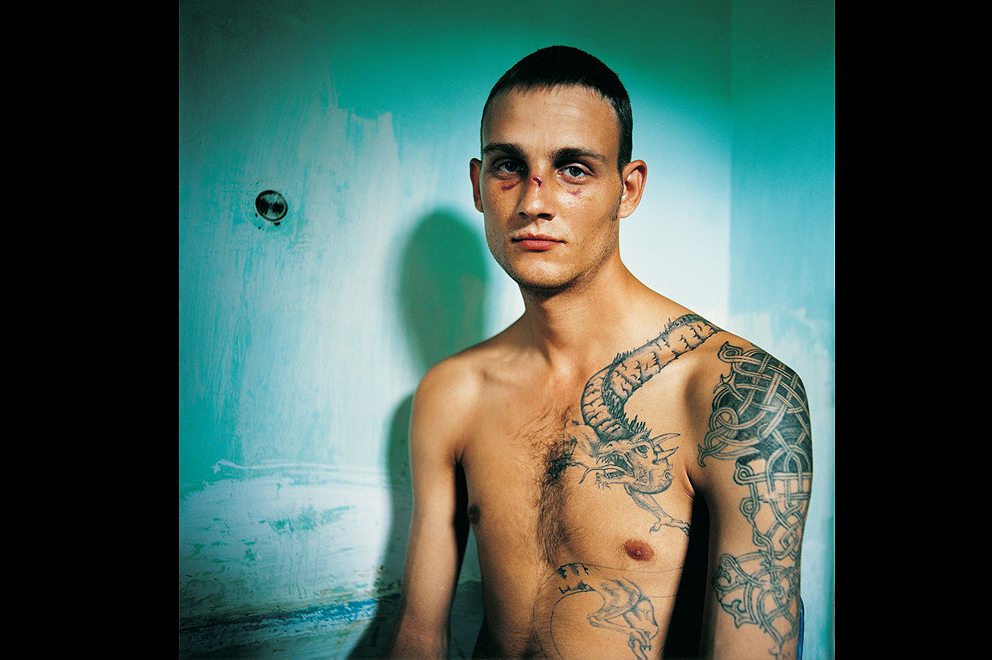

Ask Michal Chelbin what surprised her the most when entering Ukrainian and Russian prisons and she’ll tell you it was the wallpaper. Those walls, coated with blooming flowers, ocean views and grassy meadows, were the inspiration behind the name of her latest series, “Sailboats and Swans.” Over four years, the Israeli photographer shot portraits of the residents of seven prisons, sitting at times several hours with one subject. A monograph published by Twin Palms earlier this year features 62 of her images, all taken with Chelbin’s signature Hasselblad 503. At times inscrutable, always honest, the portraits immediately make you question the rather faceless word inmate: here, what you see is a person first—and that person is looking straight at you. With a body of work that explores contrast in all its shapes—the old and the new, the innocent and the perverse, the familiar and the strange—Chelbin often finds her characters and stories in the depths of Ukraine and Russia. She joined me for a Skype interview from a small Israeli village between Haifa and Tel Aviv.

Roads & Kingdoms: How did “Sailboats and Swans” come about?

Michal Chelbin: It started when I was traveling in Ukraine for a different project several years ago—a monograph entitled “The Black Eye,” which was a series of portraits of wrestlers. We passed along a prison wall, and when I realized it was a prison, I wanted to get inside. Everyone said it would be impossible but I started making some inquiries and eventually got access.

Inside it’s still a boy’s prison, which is really hell on earth

R&K: Can you tell me more about your relationship with Ukraine? When did you go for the first time and what attracts you to the country?

MC: It’s not just Ukraine, it’s Russia as well. It started in the late 90s when I was still a student and all my models were people who came to Israel in the big immigration waves from the former USSR. So the natural thing was to travel there. I went to Russia in 2003, and since then visited Russia and Ukraine several times. What I like about these countries is the mix between old and new, between the modern, the sophisticated and the classical, the rundown. The faces are great, and the light, and the backgrounds… It’s just a great setup for me.

R&K: Yes I had the same visual experience when traveling to Ukraine to find my grandfather’s birthplace…

MC: My father was born in Ukraine during World War 2, in a small town close to Rovno. Back then it was still Poland. Him and my grandfather fled west during the war.

R&K: So we’re almost connected! But back to the prisoners: describe the process in getting access. How easy was it to actually get inside and meet these people?

MC: It was very difficult to get access, and please understand if I cannot elaborate on this issue. Once inside, they usually assigned an officer to us, and spent the first few hours walking around, scouting and casting. And then we started to shoot. We were able to approach almost everyone we found interesting.

R&K: What about the actual photography? How long did you think about each pose? How much did you interact with each subject during the portraits?

MC: Some portraits took one hour, some three, depending on the sitter. I had a translator with me but usually on the set I didn’t use her and managed with my limited Russian. I never asked them about their crime before the shoot, only when the session ended. That way I didn’t think I was shooting a rapist or a killer. It’s a person. After the session ended, we talked using the translator about where they were from, their crime, their families…

R&K: What were the conditions like in these prisons? What surprised you when you entered the buildings?

MC: Everything is very basic. What surprised me was the wallpaper and the aesthetics. It’s not just cement. You sit in a boy’s prison situated in an old monastery, the building is beautiful, the wallpaper is surreal… But inside it’s still a boy’s prison, which is really hell on earth. It’s teenagers locked together, fear in their eyes. Some become sex slaves for others. It’s terrible. I could sense they were constantly on the watch. Some kids can spend three years there for stealing a cellphone. This is something that I felt when shooting this series: anyone can end up in a prison. It’s life circumstances.

R&K: How long did it take you to complete the series and how many photographs are in it?

MC: It took about four years, going to seven different prisons in Russia and Ukraine. In the book there are 62 images. It is a continuation from my body of work with the same aesthetics, the same visual language I typically use… The themes also. I usually focus on visual contrasts and things that seemingly don’t mix. In the prison work, there’s the contrast between the prisoners and the background for example… There’s also the desire for fame, the desire to be heard. Before they are prisoners, they are human beings.

R&K: How did you start your career in photography?

MC: I started when I was 15, in the photo department of my high school. Then I did my military service in Israel as a photographer. After, I worked as a news photographer but I was fired because I was always late. I went to the Academy for the Arts and started to work on my own personal projects. I also shoot commercial work and editorial assignments for magazines like the New Yorker and the New York Times. Recently, I started shooting video installations. At the moment I’m working on a project about teenagers in Ukraine, but I don’t want say more… Once I get an idea, I go and shoot. I don’t believe in talking about it too much.

You can buy “Sailboats and Swans” from Twin Palms