What a search for one of the US’s most-wanted Afghan financiers can tell us about life after war in Afghanistan.

KABUL, Afghanistan—

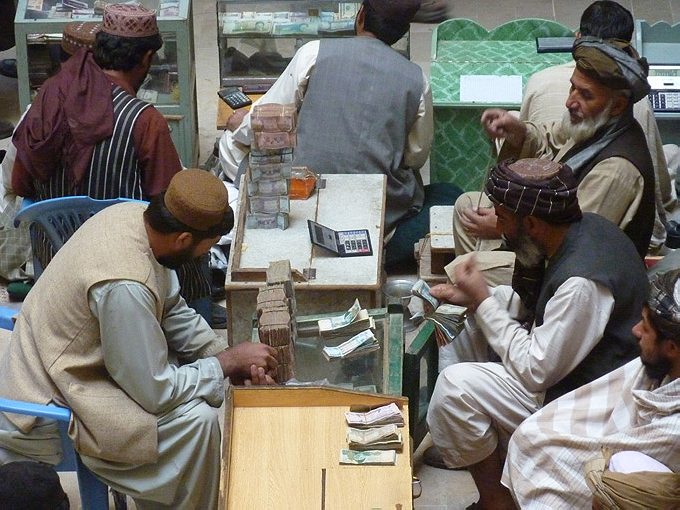

Shop 237 lies on the second floor of the Serai-e-Shahzada currency market in old Kabul. A warren of echoey walkways and dingy stairwells, the bazaar is home to a brotherhood of money dealers who will gladly swap your hundred dollar bills for Afghanis, Iranian tomans or Pakistani rupees. Questions are few, reputations all. Business is done to the clink of tea glasses and the purr of electronic counting machines.

I was looking for Shop 237’s owner, a man called Haji Khairullah. Even before I crossed the threshold, something felt wrong. Somebody had used a can of sky-blue spray paint to obliterate the storefront sign, sparing only the tips of the looping script spelling out Khairullah’s name. Inside, two young servers lolling behind the counter seemed wary of strangers. No tea was served, nor did any customers call. Of the handful of idlers killing time inside, only a wiry chain-smoker, a man with twitchy energy, seemed willing to talk.

Khairullah was in trouble, he said. Clients were grabbing him by the collar and demanding their cash. When asked why, the man’s brow furrowed. “A problem with the government,” was all he would say. I left a business card, and his attention snapped back to his cigarettes. Above the door, a Koranic inscription had been spared the onslaught of paint. It read: “And God is the Best of Providers.”

In the cloistered fraternity of Afghanistan’s moneymen, Haji Khairullah was king. No matter how mountainous the cash pile, or how tight the deadline, he would move your funds where you need them—for the right commission, of course. A blend of self-made business mogul, philanthropist, property magnate and patriarch, Khairullah’s fortunes are entwined with a cross-border cash transfer system known as hawala (from the Arabic word for “transfer.”) A vast, parallel banking system that pre-dates the time of the Prophet Mohammed, hawala has been much maligned since 9/11 as an easy route for militants to move their funds. But without men like Khairullah, known in Afghanistan as hawaladars, the country’s economy would seize like a knocked engine. His word, until recently at least, was stronger than any safe.

The U.S. subjected him to treatment usually reserved for drug lords or terrorist masterminds.

I had first heard of Khairullah a few weeks earlier from one of the small team of American officials in Kabul faced with the near impossible task of tracking the myriad pathways through which Taliban commanders move their money. As our allotted hour drew to a close, I happened to mention that I lived in Pakistan. My interlocutor smiled and said: “Ask them about Haji Khairullah.”

The Hawaladar was being watched. A few weeks earlier, the U.S. Treasury Department had subjected him and his business partner Haji Sattar to the kind of asset freeze and travel ban the government usually reserves for suspected drug lords or terrorist masterminds. The United Nations committee in New York that monitors suspected members of the Taliban and al-Qaeda had imposed similar sanctions on both men. The announcements created barely a ripple in the media, but Khairullah had, in effect, been named as one of the biggest suspected bankers to the Taliban—a gatekeeper to the subterranean financial system that keeps the movement primed with cash.

Had all this happened a few months earlier, I would never have given Khairullah a second thought. For the past couple of years I had been working as a journalist hopping back and forth between Afghanistan and Pakistan, guided by a news agenda pegged largely to Taliban attacks, political crises and official spin. All the parties to the conflict claimed to want peace, but there never seemed to be enough time to investigate whom might be benefitting from the war. Then I started a new job with Reuters that freed me up from daily news coverage and gave me my first real opportunity to try to follow the money. This is the backstory of that search.

I decided to try to meet Khairullah, to find out whether he was indeed the man portrayed by the U.S. government, and whether his business would survive the unwelcome scrutiny. Stepping through the portal into Khairullah’s kingdom at Shop 237, I entered a cash-in-hand netherworld of clandestine finance where reality, as seen by the people who truly make Afghanistan run, seems completely discordant with Washington’s version

I would learn that the hunt for Khairullah’s presumed millions was in many respects an allegory for the West’s wider Afghan dilemma. The campaign to shut the Hawaladar down raised the same question that lurked behind every decision made by the men and women leading the war—from the lowliest platoon sergeant to diplomats and four-star generals and the policy-makers in the White House. How could you hope to achieve the outcome you wanted in a country where the worldviews of insiders and outsiders so often clashed? In such an environment, did even the most well intentioned acts inevitably result in harm?

A cold vein of fear runs through Kabul over what will happen in 2014 when most foreign troops have withdrawn, a gloom that has coloured my own opinion of the Western project. But maybe my pessimism is misplaced. Perhaps the scaling back of outside influence will allow Afghanistan to find an equilibrium that would never be possible under the direct tutelage of foreigners, something between Taliban and imperious outsiders. Looking for the truth of a man like Khairullah might give me the answer. .

Finding Shop 237 had been easy enough: the U.N. sanctions committee had published a list of Khairullah’s offices on its website. A few days after my visit I received a call from a man—let us call him Fazal. He wanted to know what I had wanted. Meet me at the Safi Landmark in Kabul, he said, and we can talk.

A lot of people have made a lot of money since the fall of the Taliban, and a lot of that money has been poured into concrete. Located at a busy junction in the centre of the capital, the Safi Landmark hotel and shopping mall is both a symbol of the prosperity of the post-Taliban elite, and an occasional magnet for attacks by suicide squads seeking to persuade Kabulis that the insurgents, not a plutocracy of war contractors, will have the biggest say in Afghanistan’s future. I was having lunch in the hotel restaurant on February 14, 2011, when a suicide bomber killed two guards at the entrance. A frantic waiter insisted that I settle the bill as explosions and gunfire boomed in the street below. At the time I had promised myself I would never again enter the building, but a series of heavy steel doors had since been installed, and the mall bustled with customers shopping for air tickets, mobile phones and jewellery.

Fazal arrived at a cafe in the basement accompanied by a burly man in his 30s. To my eyes, he had the stolid look of a working man, not the bookish aura I might expect from a wizard of the Hawala trade. But his name was Asmatullah Helmand, and he was the manager of shop 237 and a core member of the Khairullah clan.

Over cappuccinos, Asmatullah made his case. The allegations against Khairullah were all lies, he said. In fact, the family business had been providing a lifeline to the Americans. Khairullah’s many customers included hauliers contracted by the Pentagon to truck supplies to U.S. bases scattered across Afghanistan, without which the war effort would rapidly clank to a halt. The Khairullah family had been more worried about the risk of reprisals from the insurgents than the Americans. “We’d always been afraid of the Taliban,” Asmatullah said. When Afghan TV broadcast news of the sanctions, “everyone was shocked.”

In spite of the moribund ambience of Shop 237, Asmatullah insisted that the family was still very much in business, and he promised to ask Khairullah if he would be willing to grant an interview to Reuters.

Categories of friend and foe lie on a continuum; there is rarely a sharply drawn divide.

For a man Washington believed was a master of the occult art of moving Taliban money, Khairullah seemed surprisingly well connected to the government the movement was trying to overthrow. Loyalties in Afghan conflicts tend to be fluid, but in the Pashtun south, where the Taliban has its roots, there is even greater ambiguity. Local officials, village elders or members of the security forces may sometimes have personal ties to Taliban commanders fighting the government, even if they are fierce opponents. Categories of friend and foe lie on a continuum; there is rarely a sharply drawn divide.

Nobody offered a stauncher defence of the Hawaladar than a member of parliament from Kandahar province named Sayed Muhammed Akhund. A former Mujahideen fighter grizzled from his years bushwhacking terrified Soviet conscripts during their doomed Afghan expeditions of the 1980s, Akhund retains something of the Kalashnikov-and-flipflops demeanour of his guerrilla youth, albeit with the later-life ballast of a mild paunch. I visited him in his house in Kabul where teenage bodyguards in fatigues lounged on the carpet, their guns propped up in the corner. Akhund, reclining on a cushion, waved away the U.S. accusations against his friend with the casual disdain of a man swatting flies.

“I guarantee that he’s not involved in drug trafficking or supporting the Taliban,” Akhund said. “I haven’t seen even a jot wrong about him.”

‘He must have had some tip-off, some knowledge that the raid was coming.’

Khairullah had called Akhund in a state of high anxiety some weeks earlier and had asked him what he should do about the sanctions. “He’s a very good man and I don’t know why he’s been blacklisted,” Akhund said. He then spent a few tantalising minutes trying to raise Khairullah on his mobile while I sat across from him—without success. As I left, he insisted I accept a cardboard box filled of juicy, fist-sized pomegranates, Kandahar’s signature fruit.

Khairullah’s network of sympathisers seemed to extend within the administration itself. FinTRACA, the Afghan financial intelligence unit, occupies one of the crop of gaudy but palatial buildings that have sprung up in Kabul’s muddy streets since the Taliban’s ouster. The man in charge is Mohammad Mustafa Massoudi, one of a generation of courageous young Afghan technocrats battling to stitch a more enlightened form of government onto the patronage machine that has evolved under President Hamid Karzai. Massoudi explained that he had ordered Afghanistan’s banks to freeze Khairullah’s accounts, but they they had found only $20,000—a fraction of the sums he was suspected of moving. “He must have had some tip-off, some knowledge that it was coming,” Massoudi said.

Khairullah certainly was not shy of lobbying the government directly himself. Haji Najeebullah Akhtary, the head of the Serai-e-Shahzada exchange, said he had received a frantic call from Khairullah who told him he was intent on meeting President Karzai to enlist his help to overturn the sanctions. (The meeting never materialised). Later, I visited one of the offices of the National Directorate of Security, Afghanistan’s intelligence service, guarded by a row of Kabul’s ubiquitous concrete blast walls. An intelligence officer explained that Khairullah had sent one of his brothers to visit him to appeal for his help in fighting the sanctions, but the U.S. files on the Hawaladar remained classified. The intelligence official had no evidence of his own to suggest Khairullah was involved in Taliban finance, only suspicions fuelled by his meteoric rise. “Thirty years ago he had nothing,” the official said. “My heart says that he is involved in drug trafficking.”

Here was the dilemma that makes Afghanistan so complex: the distinction between “government” and “insurgents” is an easy one for foreign powers to latch on to, but it is also such a monumental oversimplification that it does more to obscure reality than reflect it. Khairullah was part of a broader class of influential businessmen, elders and powerbrokers who naturally serve different interests at different times. Playing all sides in Afghanistan an insurance policy, and an art form. Far from undermining their standing, this fleet-footedness bolsters their credentials as survivors.

To understand a man like Khairullah means understanding his networks—a lattice woven during Afghanistan’s 30 years of turbulent history in which individuals may have found themselves in or out of government as the wheel of fortune turned, but whose personal magnetism endured. This was the context that took years for outsiders to understand, and which so often went unseen. I would need to visit Kandahar, the heart of Khairullahs’ Hawala operation, and the place where the Taliban movement was born.

Flanked by brooding escarpments, Kandahar city is roughly the shape of a diamond, its honeycomb of densely packed dwellings rendered in darker hues than the gentler, desert palette of Afghanistan’s southern plains. The city, so often defined by its role as the former seat of the Taliban theocracy, is not altogether unpleasant. The light is different here, sharper yet softer than in Kabul, and the air clear. Driving through the centre, the car window frames unexpected moments of beauty: the turquoise cupola of a mosque glimpsed through an alleyway; a policeman earnestly directing a honking stream of Corollas and tuk-tuks; a flint-faced motorcyclist in billowing robes. In a bulbous symbol of civic pride, a plinth outside the governor’s office bears a monster-sized model of a pomegranate. There is no equivalent monument to the province’s prolific poppy.

Highway One—the ring road that links Afghanistan’s major cities—connects Kabul and Kandahar, but a days-long drive through territory contested by a firmament of trigger-happy factions would have been unsettling, at best. I took one of the fleet of geriatric jetliners plying the route to the airport on the outskirts of the city. A Kandahari friend met me and we drove into town, passing a convoy of U.S. trucks and armoured vehicles, their headlights blazing at midday, gun turrets twitching.

On the second day in Kandahar, three less fortunate police were killed by a smaller bombing on the other side of town.

Kandahar felt safer and busier than it did when I first visited in 2010, when U.S. forces deployed in the Obama administration’s troop surge were launching operations to overrun Taliban strongholds in the surrounding districts of Arghandab, Zhari and Panjwai. The thinking back then was that the U.S. had to break the Taliban’s grip in Kandahar to turn the direction of the wider war. The Americans had succeeded in capturing plenty of villages where the white Taliban flag had once fluttered, but the movement’s operatives were still active on the city streets.

A few months before I arrived, a remote controlled truck bomb had very nearly killed the police chief, General Abdul Razziq—a youthful tribal leader with a boyish grin and a reputation as one of the Taliban’s most ardent antagonists. U.S. officials suspected Razziq had been a major beneficiary of the heroin trade during his previous post as chief of Kandahar’s border police (Razziq denies this), but his demonic pursuit of the insurgents had prompted NATO to turn a blind eye to his suspected sideline, and he was now one of the most powerful men in the province. He had survived the assassination attempt—the latest of many—by pure chance: an American official told me that an SUV had happened to overtake his convoy and absorb the brunt of the blast. Razziq suffered nasty burns, but his latest near-death experience burnished his mystique. On the second day of my visit, three less fortunate police were killed by a smaller bombing on the other side of town.

The U.N. website placed Khairullah’s counter at Shop 25, on the fifth floor in Kandahar’s currency market, a seven-storey emporium in the city centre. A policeman lounging in a plastic chair provided a token guard; no stick-up artist would be foolish enough to invoke the ire of the Hawaladars and their unforgiving clients—whichever side of the war they happened to be fighting.

Inside, Kandahar’s unofficial banking system was held together by a limitless supply of rubber bands put to work disciplining bulging stacks of notes. Hawaladars arranged brick-sized wads of Afghanis into towers teetering atop glass cabinets engorged with more notes, or fanned their currency like poker hands. Apprentice boys scurried back and forth bearing steaming glasses of green tea poured from oversized kettles. Pairs of sandals placed outside the doors of currency shops attested to the don’t-blink-first bargaining wars being waged inside by their owners, but the strongest energy radiated from an informal trading floor, where dealers gathered in a scruffy atrium craned their necks to haggle with counterparts leaning from a gallery above. Both sides barked rates, brandished trilling mobiles or swapped obscure hand signals. Khairullah’s shop was located several levels higher, but the glass doors were locked and nobody seemed to be home.

Another man was easier to meet: Haji Qandi Agha, the president of the bazaar. A kindlylooking gent with a regal grey beard and a turban that glowed with an ivory sheen, the Hawaladar perched cross-legged on a cushion with the demeanour of a meditative gnome. As we talked, a client, a sullen man with a skull cap swept back on his mop of hair, slouched up to the counter and fished a grubby sheaf of notes from his waistcoat. Qandi Agha glanced at him. “For example, this man is sending money,” he said. “What if the government or America captures him and says he’s Taliban? Is it my crime?”

As for the U.S. accusations against Khairullah, Qandi Agha said he was baffled. “When we went to his office, we only saw people changing money or drinking tea or eating sweets,” he said. “There was no talk of the Taliban or heroin.”

Clear-cut answers on Khairullah would always be elusive, but the mystery seemed to deepen when I met Haji Agha Jan, another Hawaladar with a hard luck story. A man with a wispy beard and lively dark eyes who seemed practised at greeting Kandahar’s capricious fates with a shoulder-shrugging grin, Agha Jan punctuated his tale by spitting gobs of green tobacco into a silver spittoon.

One night in October, 2011, Agha Jan heard something outside his house in District Nine, a maze of lanes in the north of Kandahar renowned as a hideout for Taliban infiltrators. I remembered driving through the area in the summer of 2010 in a U.S. Army armoured vehicle. Kids hiding in shopfronts threw stones that clattered off the carapace. It was not a place to linger. So when Agha Jan heard a commotion outside his home, he had instinctively grabbed his handgun and started pushing bullets into the magazine.

As it turned out, it wasn’t the Taliban who had come knocking, but American and Afghan troops. They blindfolded Agha Jan and his son and took them to the nearby Kandahar Airfield, a military base squatting in the desert south of the city. Confined to a one-man cell, Agha Jan could only tell the time when guards called out the Muslim prayer hours or by glancing at his captors’ watches. His interrogators were obsessed by the contents of his books—hand-written ledgers recorded in spidery biro dating back 18 years.

“I told them, ‘Yes, I am sending money through Hawala, but not Taliban money’,” Agha Jan told me. “It doesn’t have ‘Taliban’ written on the money’.”

He was released 25 days later—minus 2.3 million Pakistani rupees ($24,000) and four gold necklaces seized during his arrest. Agha Jan spread out documents on his carpet detailing his claims for his lost items. One of them, a letter signed by a U.S. Army Captain, showed they had been rejected.

Had Agha Jan’s captors made a mistake? Or had they simply not found enough evidence? How could they hope to decipher the riddles of the scribbled digits and inky thumbprints peppering his account books? If the interrogators had been wrong about Agha Jan, could they have also been wrong about Khairullah? It would not be the first time that Afghans had suffered as a result of a case of mistaken identity by American forces. I emailed an inquiry about Agha Jan’s case to ISAF, the international force in Afghanistan, but they said they had no information available.

Another Hawaladar, Haji Qasim Mohammed, had not been so fortunate. A familiar face in the market, Qasim had been taken from his home by U.S. and Afghan forces a couple of months before my visit. Nobody knew where he was being held. I would later learn that he had also been sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department on suspicions of channelling millions of dollars to the Taliban. Khairullah was wise to be lying low.

There was little love for the U.S. military among Kandahar’s Hawaladars, and certainly no shortage of character witnesses for Khairullah. Known for his Islamic piety, the patrician dealer had, his peers said, earned their respect by organising disaster relief for poor villages struck by floods or earthquakes, or more quotidian assistance like helping to fund wedding feasts and pilgrimages to Mecca.

Keep in mind, Kandahar is a place where U.S. troops set up checkpoints made from concrete T-Walls on all the main roads into the city, in a scheme reminiscent of medieval castle gating. If you’re a man of fighting age, coming into Kabul means at the very least having a U.S. soldier point an Iris-scanner into your eyes. It just makes it all the more brazen if —as the U.S. Treasury asserted— Khairullah had been running the equivalent of a Taliban ATM from the fifth floor of Qandi Agha’s currency market, unnoticed and unimpeded.

In the Ayno Mina luxury housing development, unbuilt houses remained figments of an architect’s imagination.

A few days later, we drove out to Ayno Mina, a prestige housing development on the edge of Kandahar built by relatives of President Karzai, the like of which had never been seen in Afghanistan. Several people believed that Khairullah had invested heavily in the scheme and suffered when a war-inflated real estate bubble had burst, plunging him into crisis even before he was sanctioned. Though prices had indeed fallen, the estate had lost none of its nouveaux riche lustre. Avenues of imposing tile-roofed houses, guard posts and fountains presented a dizzyingly different vision of Kandahar than the mud-brick labyrinth of District Nine.

Undaunted by the rollercoaster prices, developers were planning a second phase dubbed New Ayno Mina. Unlit lampposts marched alongside deserted roads laid out in the style of an American suburb; the unbuilt houses remained figments of an architect’s imagination. As the sun dipped towards serrated hills beyond the city, a gang of teenagers played cricket on a deserted stretch of tarmac.

As we drove back to Kandahar proper, my friend spotted an estate agent acquaintance. We stopped and shared a flask of green tea. The broker said Khairullah had visited his shop a few months earlier to try to sell 24 plots in New Ayno Mina for $360,000. Judging by the tarmac wasteland we had just traversed, this seemed like an optimistic sum. “His face told me he was very worried,” the estate agent said. “He wanted to sell very quickly.”

I pictured Khairullah pacing the shop, cradling prayer beads, his mind churning with thoughts of dollars, Afghanis and rupees.

My source said he had seen Khairullah visit Mullah Omar’s compound on perhaps 20 occasions.

On my last day in Kandahar, I met a man who was in a position to fill in some of the blanks. For multiple reasons, he cannot be identified, yet I would come to believe his version, which corroborated other, more fragmentary testimony I had gathered.

Khairullah, the contact said, had first shown his entrepreneurial streak as a teenager, when he started selling sweets from a handcart in a village in his native Helmand Province. He soon graduated to the Hawala business, but would only hit the big time when the Taliban came to power in the mid-1990s, and Mullah Mohammed Omar, the movement’s spectral founder, ruled his Emirate from Kandahar. Khairullah, according to this contact, was a member of a coterie of opium dealers who revolved in a lucrative orbit around the Taliban leader. My source said he had seen Khairullah visit Mullah Omar’s compound on perhaps 20 occasions. “He became close to the Taliban,” the source said. “He bought drugs and sold them and made lots of money.”

Another source, a member of Kandahar’s provincial council, explained that Khairullah owed his wealth to one of the great con tricks of modern diplomacy. In 2000, Mullah Omar banned poppy cultivation, ostensibly to crack down on the heroin trade. Desperate to earn a grain of international respectability, the Taliban could present the move as an act of responsible global citizenship. Farmers, terrified of Taliban reprisals, rapidly complied. The sudden dearth of opium supply caused a predictable spike in prices. Mullah Omar’s clique of traffickers, who had prudently amassed significant stockpiles, made overnight fortunes.

When the Taliban fled to exile in Pakistan under a cyclone of U.S. bombs in 2001, it would have been only natural for their usual Hawaladars to continue working with them. After all, the Taliban command remained largely intact as a “shadow” government in exile. If a slew of media reports and the testimony of former Afghan counter-narcotics officials were to be believed, then influential figures within Karzai’s administration, not just the insurgency, were also major players in the heroin trade. After all, opium trafficking was not necessarily regarded as a crime in Kandahar. Mahmood Karzai, one of the president’s most controversial brothers and a developer of Ayno Mina, summed up a widespread feeling: “During the Taliban, 80 to 90 per cent of the businessmen, they were doing drug trafficking,” he once told me. “That was a legitimate business. I think it’s extremely unfair to attack people for something that everybody was doing.”

As I joined the queue to board the plane to Kabul, I sensed somebody trying to catch my eye. I turned to see Asmatullah Helmand, the heavy-set manager of Shop 237, standing behind me. He smiled. The family had known I was in Kandahar asking questions about Khairullah. He again promised to try to fix a meeting with his boss.

A haunted, closed-off city that the rest of Pakistan prefers not to talk about , Quetta has long played an enigmatic but pivotal role in the games of espionage, influence and insurgency playing out across the Afghan frontier. It was in Quetta, to the frustration of American commanders, that the Taliban leadership found sanctuary in 2001, patiently regrouped and then launched its comeback bid. And it was to Quetta that Khairullah fled soon after news of the sanctions broke.

Pakistan’s security establishment, long accused of supporting the Taliban, is understandably averse to the idea of outsiders poking around in Quetta, and obtaining official permission to make an independent visit to the city as a foreign journalist is virtually impossible. Even if I could have bluffed my way through the small airport, venturing into the neighbourhood housing Khairullah’s office would have been too dangerous. The U.N. website helpfully provided an address. I would later learn that his premises occupied the first-floor of a nondescript building opposite a motorbike repair shop, around the corner from a market known as the Kandahari Bazaar. The office was even more nondescript than Shop 237 in Kabul. In Quetta there was not even a sign, just a white metal door.

It was only when I had more or less given up hope of speaking to Khairullah that the call came. Three months after I had first visited Shop 237, he had decided to grant Reuters an interview. Working with a Pashtu-speaking go-between in Islamabad, I would speak to Khairullah by telephone.

Pakistanis who are not conversant in Pashto have been heard to say that the language sounds like rattling a metal box full of stones. This is unfair: the voice coming down the line was clear and precise. And it was also hot with righteous anger.

“I am a businessman, and a businessman is like a ram. Anyone in authority can come and grab it by its neck and slaughter it,” Khairullah said, with rustic Pashto lyricism. “My life has become hell. I have lost my credibility and reputation. I have been declared guilty without any verdict from a judge.”

Khairullah stoutly rejected that he had any link to the Taliban or the heroin trade. And he demanded that the U.S. pay damages for the trouble his business had suffered as a result of the sanctions. “The Americans and the United Nations have persecuted me,” he said. “They will have to compensate me for my losses.”

Khairullah’s outrage was sincere. After all, even if had knowingly served the Taliban at his counters—which he denied—it must have seemed more than a little unfair to him that he had been targeted. However much money Khairullah was moving, it was an open secret that President Obama’s troop surge had provided a huge boost to the Taliban’s war chest. Insurgents had extorted millions of dollars of American taxpayers’ money through protection rackets run on contractors implementing U.S.-funded aid projects or running the haulage companies the Pentagon needed to prevent its troops running out of food, water and fuel. It wasn’t just the Taliban that was minting money; vast profits had been made by U.S. private sector contractors as well. Afghanistan was proof once again of the eternal truth that war is a business. Canny players on all sides were taking their cut.

I had heard that the U.S. dossier on the Hawaladar’s activities as a suspected Taliban financier was one of the thickest of its kind. Yet the file was kept secret. Khairullah was quite correct—he had been declared guilty by faceless accusers on the other side of the world, on the basis of evidence he would never see.

In some respects though, Khairullah was lucky. Only his accounts had been frozen. The classified process that had placed him on the sanctions list was reminiscent of the opaque system that allowed Barack Obama, the US President, to personally order the killings of suspected militants in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Yemen by CIA drones.

Khairullah was undoubtedly a man with many friends.

Whatever the U.S. government might say about Khairullah, he was undoubtedly a man with many friends. The currency bazaars in Kabul and Kandahar and other cities are the lungs that keep Afghanistan’s cash-in-hand economy alive and the men who run them are not to be trifled with lightly. I was left wondering whether any gains the U.S. might have made in disrupting Taliban finances by imposing the sanctions might have been outweighed by the anger they sparked among a cohort of Afghan businessmen who sympathised with Khairullah’s plight.

Indeed, singling him out might have been construed as a particularly perverse move given that the man who would theoretically be in charge of any attempt to arrest him, General Razziq, the Kandahar police chief, had himself been identified by U.S. officials as a suspected significant participant in the heroin trade—despite his protestations of innocence. The difference, of course, was that Razziq had sided with the West, and the Taliban clients Khairullah was accused of serving had not.

This convoluted mismatch in perceptions would recur in different forms throughout the war. A Kandahari acquaintance told me over dinner in Kabul one evening that most people in his province were certain the U.S. was backing the Taliban as part of some inscrutable, regional power game. How else to explain a superpower’s failure to extinguish an insurgency waged by young men armed with AK-47s and roadside bombs made from fertiliser? When President Karzai outraged Washington by accusing the U.S. of colluding with the Taliban earlier this year, he was not telling Afghans what to think: he was desperately trying to prove he thinks the same way as many of his fellow Kandaharis.

‘It’s like a three-dimensional game of chess,’ said one U.S. Army captain.

This gulf was one of the reasons why predicting what might happen next was so difficult, whether it be in an individual village, a province or the country as a whole. I had a conversation once with a captain from the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division holed up in a base in Arghandab, a valley north of Kandahar, as he described the complexities his battalion faced in figuring out how best to influence rival camps of elders. “It’s like a three-dimensional game of chess,” he said. Understanding the rules would be hard enough—winning harder still.

Ultimately, the future of Afghanistan won’t be determined on the battlefield, where the Taliban and Afghan troops will be locked in a drawn-out stalemate. Rather, it will be shaped in the deals done by the country’s power-brokers as they jockey for advantage in the new political landscape that will emerge next year, when President Karzai steps down and the security handover to Afghan forces reaches its conclusion. As a man with ready access to funds, there is little doubt that Khairullah’s services will remain in demand, whether his clients are seeking to fund election campaigns, or buy guns.

And so, Khairullah seems far from finished. While he may be fuming at the U.S. and U.N. from his Quetta headquarters, I was told by a Western official that he still has little trouble raising six figure dollar sums—in cash. And his reputation, though damaged, is by no means destroyed. “He is not a thief, he is not a bad man, he is not a trickster,” said one of the Hawaladars in Kandahar. “If he starts working again, he would be the first man I would trust to transfer my money.”

[Top image ©Thomas Dworzak/Magnum Photos]