Fighting tradition: the life of Yim Phala, 17, a female Pradal Serey kickboxer in Cambodia.

Yim Phala’s training routine begins with crunches, each rep completed by a shirtless young man walloping her stomach with a concrete pole, followed by 30 punches to the face from her trainer wearing with a jab pad. By 6 a.m., as the Cambodian sun begins baking the capital, Yim is halfway into a 10-kilometer run through Phnom Penh’s outlying slums and roadways. Later, she practices endless combinations of punches and kicks and spars with her fellow students, many of them male—all to master the brutal martial art known as Pradal Serey, or Khmer Kickboxing.

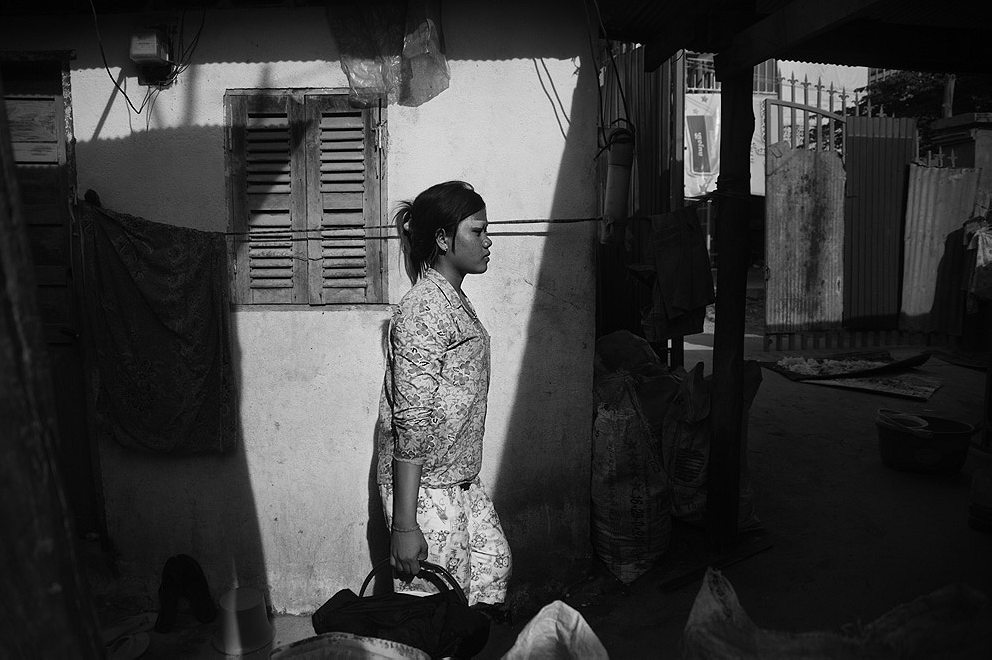

Yim, an eighteen-year-old girl from a village in Kratie Province, about 60 miles northeast of Phnom Penh, is one of the sport’s few female competitors. She moved to the city last year to live and train at Pho Chey boxing club, which is little more than a covered area between two single-story dwellings on the outskirts of the city. This morning, a ragged hen followed by a brood of chicks runs under two punching bags, and boxing gloves and jab pads hang from nails on the wall.

Pradal Serey, which combines kicks and punches with elbow and knee strikes, dates as far back as the 9th century and is one of the most popular sports in Cambodia. In the Phnom Penh region, there are some fifty Pradal Serey matches each week. The sport remains heavily male-dominated; in a country with a dismal score on the United Nation’s Gender Inequality Index, and where women are expected to marry young and stay at home, female fighters like Yim are rare. But with the Cambodian government pledging to combat gender inequality, coupled with Prime Minister Hun Sen’s vocal support for women’s inclusion in the national boxing championships has led to the ranks of female kickboxers swelling with rural girls keen to train and take a shot at the big prize money.

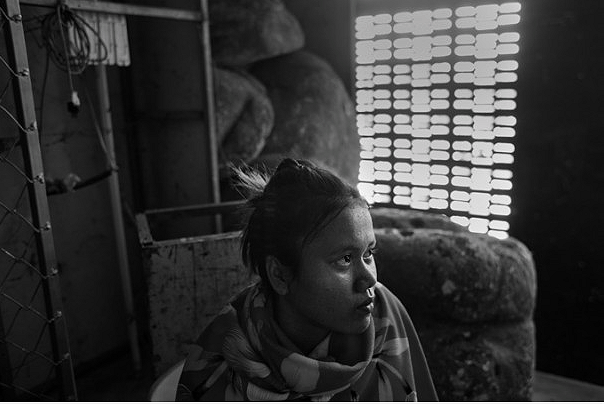

Yim looks older than her years, with wide shoulders, thick limbs, and a reserved manner. She is the youngest of six children and has three years left of schooling, but her parents are supportive of her decision to pursue boxing. “My family supports me 100 percent. They worry about me getting injured, but give me the freedom to do what I’m interested in,” she says. “I have always been interested in boxing. I like to learn self-defense and I can have a good standard of living doing this.”

Yim lives with her trainer and his family and gives her wages to the trainer’s wife, whom she calls “aunt” although they are of no relation, a common custom in Cambodia. (Women usually control finances in Khmer households and it is not unusual for cohabiting guests to hand over their wages and receive an allowance.) For each fight, Yim receives and 350,000 Cambodian riel ($87) if she wins and 300,000 riel (about $75) if she loses. Last year, Yim won 13 of the 18 bouts, earning above the average wage in Cambodia of roughly $3 a day. Yim’s family is poor and she pays for her education and rent with her winnings, although she’s not yet making enough to send home to her family.

While women’s kickboxing still has a low profile in Cambodia—only one of the six television networks that broadcast weekly fights features female bouts—fans are beginning to take interest. Sambo Nung, a boxing fan from Takeo Province, says women have a long history in Pradal Serey. He brings up a story—likely apocryphal—of how female troops successfully fought back Thai soldiers during the 1120 invasion using Khmer Kickboxing. “There have always been girls boxing,” he says. Sambo’s friend, Supon, holds a more conservative opinion on the sport: “I don’t like women in boxing. Cambodian women should be modest.”

Despite her passion for the sport—and her potential—Yim says she would be happy with a more traditional life for a Cambodian woman. “I don’t mind if a man is a boxer or not, as long as he has money. I like boxing but I don’t know if I’d continue after I’m married.”

He begins smacking the boy in the face, quickly and repeatedly.

Soy So Kom, Yim’s trainer, a short, solid man in his 40s wearing a tight-fitting Dwayne Wade jersey, has been involved with kickboxing for twenty years, first as a prize-winning fighter and now coach and gym owner. “I have a trophy inside,” he says, darting into his house and returning with a bronze figurine in hand, awarded for one of the bouts of his youth. “The prime minister gave me this himself.” Soy currently trains thirty fighters and says he can have a new student ready for her first match in three months. To demonstrate how he toughens up his fighters, Soy instructs a sinewy young man sit on a stack of tires. The trainer puts a jab pad on his hand while the student winces in anticipation, and he begins smacking the boy in the face, quickly and repeatedly.

Soy has been training women for three years and he has seven female students. At the gym, camaraderie is tight between the male and female students. “The male fighters treat me like a sister,” Yim says.

But her male peers show Yim little mercy because of her gender. Today, she spars with a male boxer who kicks her in the face and unleashes a storm of body blows. (When the match is over, Yim will require stiches for a split eyebrow.) Yim steels herself, eyes focused on her opponent, and lands a punch to the jaw that sends him reeling, his mouth flapping like a marionette.

Trainer Soy says life is not always easy for his female students. “Some of their parents are not happy. They think it is not good for their daughters to do this.” But he is clearly proud of his female fighters; in fact, the only of his students to win a title was a woman named Soy Sothea, who captured the 2012 female featherweight championship.

When asked if Yim thinks she’ll ever win a championship, she flashes a rare smile. “One day,” she says, “I will win.”