Columnist Howard Chua-Eoan drinks tea in lovely, malfunctioning Buenos Aires with Jorge Luis Borges’ widow.

Cocktails & Carnage is a weekly interview column from former TIME News Director Howard Chua-Eoan. Every Thursday! Read previous columns here.

I had to get on a half-hour commuter train ride to San Isidro, a suburb of Buenos Aires, but couldn’t figure out how to get a ticket. The automated teller was kaput and I had crossed the tracks twice to get to the human teller only to find a handwritten sign saying, “I’ve gone to the bathroom.” When tickets finally started moving out of that window, I couldn’t quite see the clerk through the murky glass and stood in front of it until he yelled at me, then charged me double because I didn’t buy my tickets at the computerized stand. It didn’t matter that the machine wasn’t working. Finally, when I got on the train, no one came by to collect my ticket. Or anyone else’s ticket for that matter. I wasn’t sure where to vent my frustration. No wonder Buenos Aires has so many psychiatrists.

The ticket fiasco probably contributed to the breakdown of my language skills. I had gone out to San Isidro to conduct an interview. My Spanish had been getting better by the day and on Tuesday, my fourth day, I thought it was better than ever. But this was Wednesday and it collapsed as the interview got underway, the conjugations short-circuiting my brain as the syllables reeled backwards and forwards at the speed of, well, sound. I didn’t know that brain cells were like muscle cells, they fatigue and they fail on you. Fortunately, my colleague Hilary Burke was with me to translate. It was all very embarrassing.

We had one more interview the next day in order to chase down a lead involving Jorge Luis Borges. I didn’t know if I had any more Spanish left in me. It had taken a bit of time to get used to fact that the Argentine variation involved recognizing vos as the alternative to usted; and that most Porteños, as the residents of the capital are called, tend to pronounce the ll and y sounds as “sh.” So Castellano—what gringos and the gringo-oriented like me recognize as Spanish—is Casteshano. And villa is visha and it often doesn’t mean part of a plutocratic estate but a slum. Fascinating but confusing. And of course, not everyone in Buenos Aires pronounces ll and y that way. The upper class certainly don’t. I met very few representatives of that group but when I did, I got even more anxious about my ability to communicate and understand the language.

But back to Borges. To check out a fact about the late great pioneer of hyperlink fantasy fiction (among the other things he did), Hilary contacted his widow Maria Kodama. She agreed to meet us. Still, I didn’t quite expect our encounter with la viuda (the widow) Borges to take place at an outlet of a chain of tea shops, albeit in the fashionable Recoleta district of the Argentine capital. But somehow, it all worked out—sort of. With Borgesian intuition, Kodama sensed the debilitation of my brain cells and, without prompting, spoke in English.

She met Borges when she was 16. By that time, he was blind and never saw her face.

The Tea Connection at 1642 Juncal Street is elegant in a very pastel way but it also reflects the inefficiencies of Argentina’s economy—which are, unfortunately, not of labyrinthine wonders in the Borgesian vein. Maybe Monty Pythonesque. Hilary ordered a tea only to be told that the shop was out of that kind of tea because the restrictions on the circulation of the U.S. dollar made it impossible to import it. When Maria tried to order an espresso, she was informed that there was not water to express the coffee. She ordered toast and the waitress brought out whole wheat rather than the white that Maria wanted. I was luckier. The shop had the Pu-erh tea that I picked out from the menu. It was served in a lovely little pot and infuser into which hot water was poured. I was given a little 1-1/2 minute sand timer and told not to start on my tea till it had been flipped over twice. Except that on the second flip the sand sort of got stuck for much longer than two minutes. All of this felt somehow like trying to buy a train ticket.

Maria Kodama is a beautiful Argentine woman of Japanese and German descent. Her hair is white on the outside but a shade of russet brown beneath. It is very chic. She refuses to give us any clue to her age and parries questions from Hilary that would have given us a way to calculate it (though, if you want to be tedious about it, her age is surely available on Wikipedia). She met Borges when she was 16 and he was teaching English. By that time, he was blind and never saw her face. But they shared a love of northern European languages like Norse, Anglo-Saxon and Icelandic. Borges, she says, insisted that she learn Icelandic because it was the Latin of the north. She would be his companion for the last decade or so of his life, marrying him towards the end. After he died in 1986, he left everything to her—including his immense literary legacy. She runs the Fundación Internacional Jorge Luis Borges, based in Buenos Aires but which keeps her constantly traveling as fresh generations discover the Argentine master.

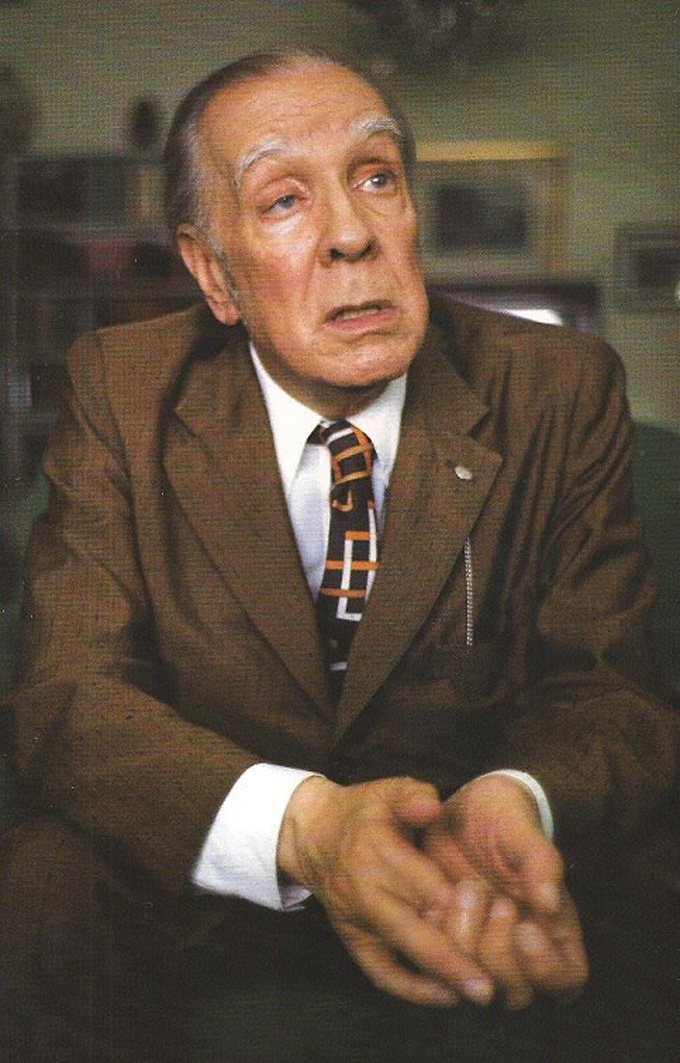

Borges, portrait by Sara Facio

Borges, portrait by Sara Facio

Perhaps again sensing my anxieties, she brings up Borges’ opinion of psychoanalysis, which was not high. She remembers the time when the blind Borges accepted an invitation to speak at a conference, unaware that it was an organization of Freudians. It was only when he was introduced that he sensed who his audience was. The first question was: And so, Mr. Borges, what do you think of psychoanalysis? His response: “I am very fond of fantasy literature.” The crowd roared. (Ironically, a section of the Palermo district of Buenos Aires, where Borges spent part of his youth and where his family had a home, is informally called Villa Freud, even though it is not a slum but rather a rather well-to-do area that has a very high proportion of the city’s psychoanalysts.)

Borges was not going to let polite language limit his visions.

He was not so good humored about his blindness, especially when it came to the language used about it. She related one incident in which a well-meaning person referred to his condition using the politically-correct Spanish words “no vidente”—without sight. Borges was taken aback. He quite forcefully told the man that the proper word for him, as harsh as it sounded, was ciego and not no vidente. A poet and artist of Borges’ prowess would of course take offense, Kodama explained, because the word vidente also means “seer” or someone who can look into the future. Borges was not going to let polite language limit his visions. It was a good lesson in Spanish for me.

But what was it that I wanted to ask Kodama about Borges? The subject of my reportorial trip to Buenos Aires once said that the writer, famously agnostic recited the Lord’s Prayer every night because he had promised his mother he would do so. Could Kodama confirm this? She smiled and said, not quite every night. He would recite it every now and then, but not in Spanish, in Anglo-Saxon. At that, my mind was blown and the rest of my language cells went kaput.