Travelling to the heart of the Holy See for libations and for the more Catholic sense of ‘spirit.’

[Vittorio Emmanuel bridge, linking the historic center of Rome with the Vatican]

For all the wonders of Rome, the Eternal City doesn’t have much to show in terms of mixology. Except for Barnum Café on Via del Pellegrino where the bartenders—ehem—the mixologists like Federico are constantly trying to impress you with their elaborations on classic formulas and wholly new cocktails. I found Barnum by way of Elizabeth Minchilli, an American ex-pat and now indispensable guide to all things good to eat and drink in Rome. On a Friday night in early October, over Federico’s lovely take on a Manhattan and several other delicious curiosities (including a tea-infused marvel that was sent over to Elizabeth’s husband Domenico), we talked about the new spirit (of the religious kind) that was sweeping up Rome, and, indeed, much of the world.

Elizabeth was astonished that tourism was still up in October, when the number of visitors usually come down because the weather cools, the days grow dark early and the air grows damp and cold. Her conclusion: it’s the new Pope. Though Jewish, she was a fan of the new Pontiff.

Other journalists in Rome have said as much. A few hours before I met Elizabeth and Domenico I had beers in the old Jewish Ghetto with Alessandro Speciale at Libreria Caffe just off Via Beatrice Cenci (a street named for an infamous 16th century parricide executed on orders of a Pope). Alessandro, who used to freelance for TIME but is now headed to work for Bloomberg in Frankfurt, says that there was very little excitement among his family and friends over the Papacy for much of the seven years he covered it for a bunch of media outlets. Now, suddenly, everyone has been asking him for a chance to be at an audience or a mass or close-up with Francis, who has been in office since his election on March 13.

Even earlier that Friday, over rich and peppery cacio e pepe and a nice bottle of the inexpensive Roman white, Frascati, at Felice in the Testaccio district of Rome, Alberto Vourvoulias—a former colleague at TIME and a year or so transplant in the Italian capital—remarked on the new Pope’s humility and broad embrace of almost all the various divisions of the Catholic church and Christianity. It made the Vatican seem vibrant and efficient, Alberto said, especially in comparison to the dysfunctional and rancorous Italian government.

The hidebound history of Italian politics was evident when another journalist friend pointed out that the former headquarters of Forza Italia—the party of disgraced former Prime Minister and billionaire Silvio Berlusconi—used to lie across the Via dell’Umiltà from a strip club. Umiltà means humility, which only added to the irony of the placement of Berlusconi’s HQ.

So, being filled with the spirit of several wines and cocktails, I decided I had to see this new Pope at work, particularly because I’d written cover stories on him for TIME and an insta-book soon after his election. His legend was growing with tales of his refusal to live in the Papal palace; his embrace of the sick and destitute in St. Peter’s Square; his sudden phone calls to those in need of comfort; his spontaneity; his diminution of the Catholic Church’s battle against abortion and homosexuality; his insistence that the work of the Church be focused on the poor and the repressed, with the unfortunate, like the immigrants drowning in their desperate journeys to the Italian island of Lampedusa. I had managed to get a ticket to the usual spectacle of Sunday mass in Saint Peter’s Square. But I was in luck. There was another big event on Saturday. Our Lady of Fatima was in town.

Oct. 13 is the date of the last appearance of the Virgin Mary to the three young Portuguese shepherds in Fatima in 1917. To commemorate that day, the statue from the pilgrimage site was itself making a pilgrimage to Rome to be venerated and blessed by the new Pope. The Virgin of Fatima is a powerfully influential icon because of the secrets she handed down to the Portuguese children. The Third Secret appears to predict the killing of a Pope and a number of high-ranking prelates by soldiers who attack with weapons, including arrows. Several years ago, when the Church finally made public what it said was the text of the Third Secret, the official line was that the prophecy involved the failed attempt to kill Pope John Paul II on May 13, 1981—and that it had been fulfilled. Indeed, John Paul II attributed his survival to a medal of Our Lady of Fatima that he was wearing on that day, believing it had deflected the bullet fired by the Turkish anarchist Mohamed Ali Agca that would have killed him.

That is fine for everyone but the conspiracy theorists who say the real secret has yet to be released and, besides, the attempt on John Paul’s life sounded nothing like the scene described even in the official secret. In any case, at least the way I look at it, it is always good for any new Pontiff to be on the good side of Fatima—just in case the prophecy is pending.

So I found myself in Saint Peter’s Square on Oct. 12 watching the statue make its rounds along paths cleared by wooden barricades, hoisted on the shoulders of various sodalities dedicated to the Virgin and her divine son. I managed to make my way to an area where seats were available and which had a good sightline to the still-distant area in front of the Basilica where the Pope would appear. Suddenly, the people around me rose. There was no cue; nothing was announced. But about a second after we all were on our feet, the massive crimson curtains over the main portal of Saint Peter’s Basilica divided and a man in white walked out.

Pope Francis is not photogenic. He walked with a limp, dragging his foot along like a burden.

His image was projected on the jumbo-trons. Francis is not particularly photogenic. He walked with a clear limp, almost dragging his right foot along like a burden. Francis has a pronounced paunch that makes it look like he stashed a thurible under the midsection of his papal whites. Even his predecessor, the cerebral and much-too-coolly academic Benedict XVI, had a better silhouette (and red shoes). Francis was wearing sensible black loafers. But his initial demeanor was vacant, his lower lip drooped. He looked tired. When he began to read from an Italian text, the first thing I noticed was his very sibilant, almost imperceptible final S’s at the end of certain syllables.

Then something astonishing happened. He dropped one hand from his text, lowered it below the lectern, in an oratorical manner. Looking up from his script, he eyes brightened and it was as if he was looking at every single member of the audience individually. As he went on, he would move his head one way or the other, raise his other hand, smile, provide a humorous aside. It was as if he was trying to engage each member of the audience in a dialogue. My Italian comes through my bad Spanish but I hung on to every syllable from the man’s mouth.

He would repeat the performance the next day at what is usually a gigantic Sunday gathering in the square. The crowds did not disappoint. And neither did Francis. To his “come let us reason together” oratory, he added homely but winning advice. The three words, he said, to help ensure a happy and successful family are: permesso (“May I?”); scusa (Pardon me); and grazie (thank you). It is the kind of loving counsel that a smart parish priest would give: except his congregation at that moment, in the square alone, was about 150,000 people. They applauded.

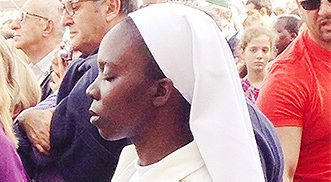

The crowd was as polyglot as they come. I was standing (no seats this time) next to a contingent of Germans and trying not to fall into a bunch of Italian pilgrims who had improvised their own chairs (umbrellas and boxes). There were Filipinos and Sri Lankans and Chinese and Poles and Czechs and Brazilians and innumerable other nationalities. But when the great prayers of the Church were intoned—the Lord’s Prayer and the Ave Maria—almost all of them started reciting them in one language: Latin. And when the time came for the sharing of the Peace, the Germans shook hands with the Italians, the Italians with the Chinese, the Chinese with the Filipinos and each with the other. And then you realize the power that Francis may be tapping into if he is successful in unifying and revitalizing a Roman Catholic Church so long caught up in crisis. Because it is then that you remember the meaning of the word “Catholic.” It means, “Universal.”