Writer Nemonie Craven is a tourist in the land of drinking, debt and desire that is her hometown

I was struck the other day when a colleague of mine, describing someone I was anticipating meeting, said, “He’s nice but… well—he’s Welsh.” As I am also cut of that cloth, so to speak, I wondered what on earth she was getting at. How could anyone in this age of identity crisis be so sure of a particular, italicized cultural copyright? “Oh you know: he’s got the black side; he’s extreme. How many Welshmen do you know who are either teetotal or alcoholic?”

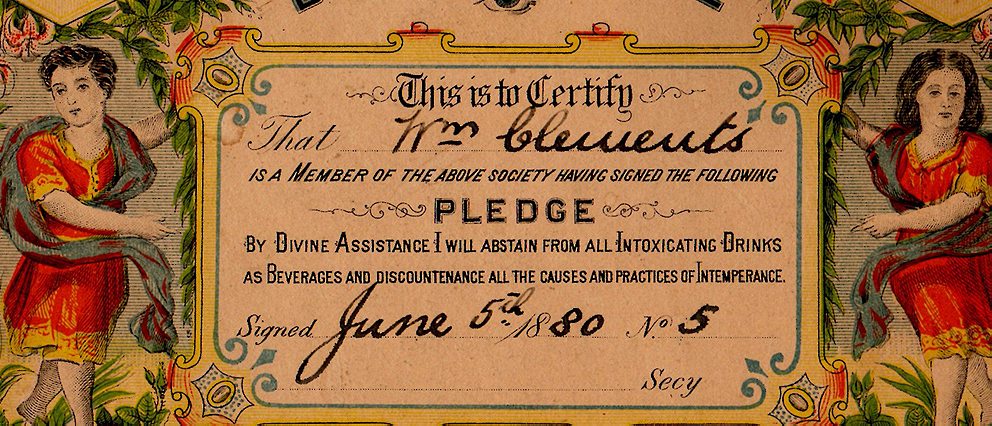

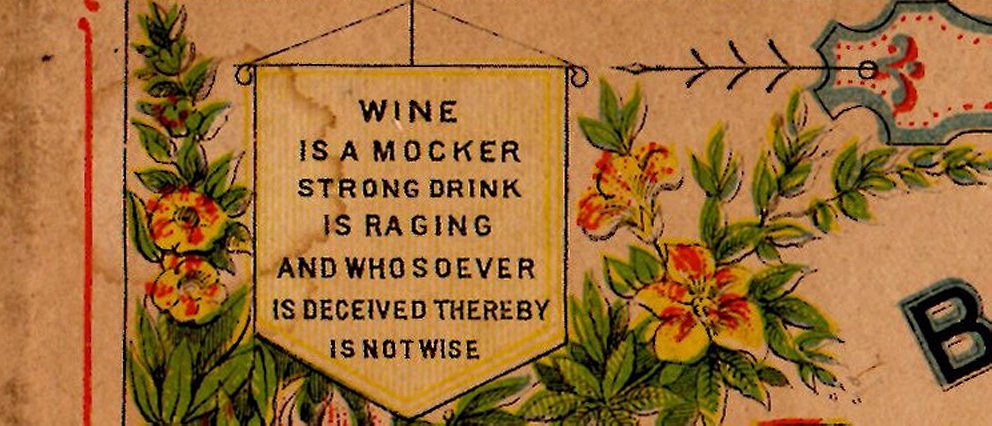

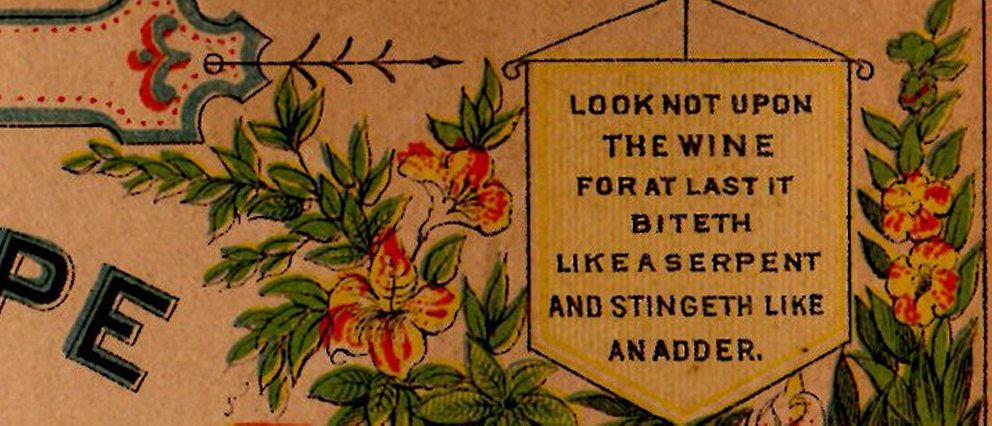

Fair point. I know lots who are both. I’ve still got my great-grandfather’s certificate proving he was teetotal from The Band of Hope Union of the Methodist Chapel: “By divine assistance I will abstain from all intoxicating drinks as beverages and discountenance all the causes and practices of intemperance.” Signed June 5th 1880.

He swore by a whisky before bed. But surely non-Welshmen can display this elaborate hypocrisy? Kingsley Amis veered significantly—lurched, perhaps – towards the latter half of the binary of teetotalism and utter drunkdom. Though, to be fair, he bypassed the first term of the binary, and therefore also bypassed hypocrisy, only narrowly bypassing a triple-bypass. Despite this, however, he probably counts as an honorary Welshman. A Welshman in spirit, we might say. Positively doused in the stuff.

In his Booker-winning The Old Devils Amis explores the alchemical properties of booze in conjuring up a misplaced sense of Welshness when Alun Weaver (formerly Alan), poet and telly pundit down on his luck, returns ‘home’ to the land of his fathers. To go In Search of Wales… presents itself to his mind as a soundbite, an opportunity to go on an extended pub-crawl and to revive a few old flames. His band of Old Devils veritably rattle through the jarring Modern Wales, ill at ease in their baggy skins, their self-loathing encapsulated by their disgust for Welsh-language signs where “Tacsi” helpfully denotes “Taxi” for ‘the benefit of Welsh people who had never seen a letter x before.’

This self-loathing rings true. The area covered by the South Wales police force may only represent 10% of the geographical area of Wales, but they are responsible for policing 42% of the local Welsh population. And, boyo, you should see them. The National Assembly for Wales has, and in 2007 assembled over £87,000 to combat the binge drinkers who befoul the land of their fathers every weekend. Let’s leave aside more recent statistics regarding the spate of suicides, amongst young people in the Bridgend area, noting only the title of Gary Owen’s play on the subject, Love Steals Us From Loneliness—a production by the increasingly innovative National Theatre of Wales performed in the Bridgend bar Hobo’s.

In 2005, of the 16 – 24 age group in Wales, 36% of men and 27% of women indulged in ‘binge’ at least once a week, according to the Office for National Statistics. According to the jargon of the Assembly/BBC Wales campaign, they got RSOD – an unfortunate acronym for Risky Single Occasion Drinking. Single occasion? Now that’s hopeful. Especially when you consider that drinking in Wales, especially in my hometown of Bridgend, is almost a vocation. It was a positive ambition for us as fifteen, fourteen-year old girls. With military precision we would enter formation out of the bouncer’s line-of-sight opposite The Welcome to Town, one-by-one dashing through the door whenever he went to pee, or nipped over to the Olympic Kebab.

We worked as a team, but have no doubts that sacrifices had to be made: one of us might get clobbered at any moment, brought down by a dodgy fake i.d., or an influx of seventeen-year olds (they could completely blow your cover). Once taken out, you would gracefully accept defeat (only after trying to get a leg-up over the back wall) and slope home for an early bath, slightly cheered by the thought of that really good film on Channel 4. Oh, how many times I rued S4C (Sianel Pedwar Cymru, Channel 4 Wales): the television station invented to compound humiliation and despair by supplanting Four Weddings and a Funeral with Sgorio or Pobol y Cwm.

But I’m getting carried away… Back to the issue. Being Welsh-in-italics. What does it mean? In search of Wales… In Search of Wales. It’s time for a pub-crawl.

And how obliging my friends are. We got completely RSOD, just like at school. The limo arrived at six, and we were amazed to find that you can actually see out. Why would you want to? But this became a very useful metaphor, as throughout the night I was an increasingly invisible observer. Eventually people couldn’t see me at all, and kept treading on me, dashing me underfoot like a well-sucked Lambert & Butler. “How can people afford this?” I asked the Oracle of Chapel Street, Bridgend. “Credit cards,” she replied. And I realised that one could become trapped like an invisible hamster on this wheel of recklessness: swiping, forgetting, remembering, regretting, swiping the memory, and starting again. A bit like sex.

I had to escape to the loo. I was out of the loop; I was a hamster spun off the wheel. You really have to care to binge drink. And I no longer did. In fact, I felt like getting mean. A befeathered girl took a step too far when she pushed in to the queue for the ladies’. “It’s alright,” she explained, still attractive, but lined, creased from binge. “I work here: I’m allowed to push in.” I contemplated a wild cat-scratch, a punch, a grabbing of hair and feather and a pluck, but I have moved on from those days and simply said, as I thought: “That’s OK. You’ll probably never have love in life.” It proved to be the meanest thing I have ever said or, indeed, done. Hush descended as The Feathered Girl (so called as my friends hid me from her in my conviction that she would slit my throat) tottered out, shell-shocked.

“That was a bit harsh,” I heard as I gently closed the cubicle door.

And I suddenly understood. Epiphany came, as I’m sure it always does, half-soaked, remorseful in a public-toilet cubicle: the binge is all about love.

You have to care to binge, to throw your body three sheets to the wind, to drain your bank account and your brain. You have to want something in return. And that something is love. Even in the state of pure sexual desire, next day no-strings-attached, it’s about love.

Acceptance into The Welcome to Town was all we could hope for at fourteen. Amis seemed to understand this, how booze and need and sex all tangle up into this horrible mess that is life. As did his friend, Larkin: ‘Beneath it all, desire of oblivion runs.’ And beneath that?

Solitude.

As towns like Bridgend grow outwards, their enormous, labyrinthine housing-estates impinging on the green, green grass of home, they lose their centre, forming a map of our selves, the old tabernacles now gutted and filled with drink. But let’s not hark back to the halcyon, hypocritical days of the Chapel and the unfulfilled Pledge; let’s try to understand this new attempt at community. Let’s try to understand what runs beneath this search for love that is Binge. C’mon, mun: let’s go on a bloody pub-crawl.

[Republished with updates from the author’s late, lamented How to Live Blog. All images from her great-grandfather’s teetotaler’s certificate. For another view of bladdered Britain, see Dougie Wallace’s bracing photoessay on the drinkers of Blackpool]