A ludicrous search for answers about Penn State, in the Sicilian city of Paternò

Heading west from the Sicilian port city of Catania, I see two things: the volcano that has destroyed Catania seven times since the age of the Greeks and, a little farther down the road, a exit sign for a city whose name would remind any American of calamity: Paternò.

My mind, slowed by the previous night’s great quantity of Moretti beer and grilled horsemeat (a Catania specialty), is not working rationally. I think of the fallen empire of Happy Valley, and I see the wisp of steam coming from the top of Mt. Etna, and suddenly I’m seized by the idea that the Sicilian city of Paternò must also be a smoldering ruin. A city of toppled statues, of lax bros cursing the gods, of old men sobbing as they mourn their good name.

Maybe one of those old men will be JoePa himself—among the many delightful ideas the Internet has about the scandal is the idea that maybe the coach is not dead, but merely living out his days under a false name in Sicily.

[More on Roads & Kingdoms: Catania, All Dressed Up and Nowhere to Go]

If that is true, moving to a town called Paternò would be quite stupid, not least because of curious Americans in rented Fiats, people like me.

I take the exit and head for the city center.

Paternò may or may not be the ancestral home of Joe Paterno. His children are likely too busy investigating Louis Freeh and the Trustees to send me an Ancestry.com report. But Sicily has given so many of its people to the United States—there are just five million Sicilians living in Sicily, compared to an estimated 18 million Sicilian-Americans. Al Pacino, Jon Bon Jovi, Joe Montana, Sicilian blood in them all.

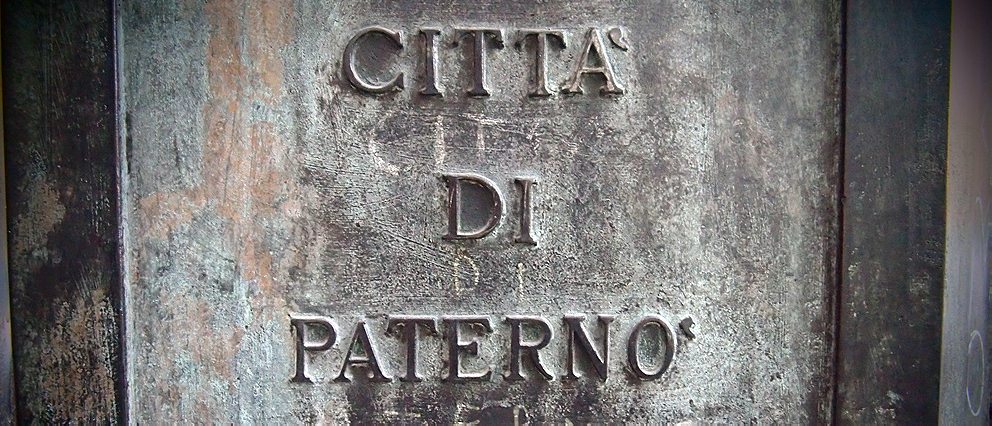

Paternò is like many smallish Italian cities, a drab ring of residential neighborhoods built around a historic center. With my friend Sabrina di Caro acting as translator, I head to the heart of this center, the plaza in the shadow of the Monastery of the Holy Annunciation.

There are nothing but men. Old men. I’ve seen this before. In Sicily, as the heat of the day eases, people emerge from their homes. Old men always take the prime real estate. Milling around the piazza now, look at Sabrina, cast a glance or three at the fit of her jean shorts, and inform her that there is another plaza for the women, not far away.

[More on Roads & Kingdoms: Denmark: Happiness, the Video]

Sabrina is undaunted. Her family is Sicilian, but she was raised in the north of Italy. She loves this island, but she has no patience for its clannishness. She takes a microphone and points it at a clutch of men sitting at the base of a statue. One of them gets up and leaves. The others stay.

First question: Have they heard of Joe Paterno, the famous American football coach?

“Ah, American football,” says one of the old men. “I have heard of one person. He’s black.”

“No, no,” says Sabrina. “Bianco. Joe Paterno is white. He’s famous, very famous, and his name is Paterno. Like this town.”

Nobody has heard of Joe Paterno.

“I don’t know anything about American football,” says one. “I am sorry. But if you wanted to talk about labor issues, I would be happy to talk.”

Now the men don’t want Sabrina to leave. They crowd around her. One, holding his car keys, invites us to drive with him to a special spot on the nearby slope of Mt. Etna. “It’s beautiful there, I’ll show you.”

[More on Roads & Kingdoms: Red Gold, the Tomato that Fuels Sicily]

We decline and go back to asking questions. Do they know of any famous paternisi living abroad? In their response, which is not even Italian but Sicilian, a thicker dialect, I hear the words La Russa. Aha! Maybe instead of willful ignorance of child buggery, we can talk about willful ignorance of the size of Mark McGwire’s.

But no, the old men are talking about Ignazio La Russa, native of Paternò and former Italian Defense Minister under Berlusconi. This La Russa only lives abroad if you consider the Italian mainland a foreign country, which these men clearly do.

And then, from behind me, a voice says quietly in Italian: I am Joe Paterno.

I turn around and see a man who, to my sluggish mind (beer, horsemeat), looks just like JoePa as a younger man. Slight build, slightly hooked nose, polo shirt. The frames of his glasses are different. He is a bit taller. But the rest seems the same.

He speaks quietly, in a gravelly voice. He has also never heard of Penn State’s Joe Paterno. His name is Biagio Paterno—he pulls out his identification card to prove it—and everyone calls him Joe. He says he has a story to tell us, also about sports, and he would like to buy us sodas and sit and talk.

[More on Roads & Kingdoms: Abkhazia, Paradise Lost]

Sabrina and I walk north out of the plaza with Joe Paterno. The old men are now sad that we are leaving. “You are wonderful people,” says one. The man with the car keys and the invitation to Mt. Etna looks crestfallen.

Paterno, 46, takes us to an empty, brightly lit café nearby. He buys us all mandarinetto, a kind of limonata but made of orange soda, with extra seltzer added to it. We are here in Sicily, home to powerful grappa and the sweetest wines, and we are drinking a reverse-engineered Fanta. I sit outside with him on Via Monastero and he tells his story.

The problem with Paternò, he says, is that the kids have nowhere to play sports.

He’s not a rich man—he’s a woodworker who specializes in the wood of orange and olive trees—but his dream of two decades has been to build a sports center for the poor youth of Paternò. The rich kids, the ones whose families have summer homes in Ragalna on the slopes of Mt. Etna and beach homes along the Ionian Sea, have plenty of private clubs, he says. But the poor, a number that is growing in the economic crisis, have nowhere. “They should be able to play football, tennis, bocce,” he says. “They should have a swimming pool.”

[More from Roads & Kingdoms: Photoessay on the Beautiful Game of Ballarò]

He says the basic equation for Paternò youth is grim. There are no jobs, and so people get involved in crime, they join the mafia. Of his childhood friends, he says, he was the only one “smart enough” to stay clear of crime. “They had family problems, or parents who didn’t pay attention.” They started small, stealing sausages from the butcher. The crimes grew, and now most of them “are not here”, he says, either in jail or dead.

“Mafia is a reality,” he says. “It’s daily life here.”

He bought the land for this sports facility—20,000 sq meters—almost twenty years ago. But in all that time, he hasn’t been able to find investors. The city hasn’t helped them. It’s the “mafia mentality” that doesn’t want to help the people, particularly the poor people, of Paternò. All he would need is a few thousand euros of private or city investment to start building his sports center. He says all this in his way: quiet, dignified, a little sad.

I want to tell him that the Penn State’s athletic department brought in more than $32 million in profit in 2010-2011, the same year that Joe Paterno’s salary—the one he forced the Board of Trustees to approve even as the Sandusky scandal was brewing—was $3 million.

That part of me that I can’t help, the part that likes to cause trouble in conversations just like this, wants to explain that his dream of sports for troubled youth sounds a lot like the dream of Jerry Sandusky’s Second Mile Foundation. I want to explain that a sort of mafia mentality of its own—protecting the powerful at all costs—led to a coverup of crimes that would make even Bunga Bunga Berlusconi, aficionado of teenage whores, red with anger. I want to make Sabrina translate and tell this Joe Paterno exactly what those crimes were, just to see the look on his face.

But I stop myself before I do any of that. It occurs to me that I am just a stupid American, full of horsemeat and beer, with a disgusting story from across the ocean. I should hold my tongue. So I just nod and listen, and when we are done with our sodas, I shake Joe Paterno’s hand, and we part ways in peace.