On the hunt through Saigon, in search of the past, present, and future of the banh mi.

“Chili!” says the elderly Vietnamese lady, ushering me closer. She seems eager to help and apparently already knows what I want. Taking one of the pre-made sandwiches from the counter, she slips off its paper wrapping to reveal the short, golden bun inside. Its crackled crust is splayed to demonstrate its contents. After two years in Vietnam, and countless banh mi breakfasts like this one, it seems I still look like a tourist.

“Chili,” she repeats. “Chili okay?”

Several slices of fire smile up at me from between the folds of meat, paté, pickled vegetables, and cilantro.

“Ớt được,” I reply in my mangled Vietnamese. “Chili okay.”

I’m at Như Lan, a restaurant, bakery, delicatessen and Ho Chi Minh City institution, having served homemade banh mi, among other local specialties, from its busy downtown kitchen since 1968, when the city was still officially known as Saigon (a name still used today) and the war with the North was raging. Almost 50 years later, helped by the West’s growing infatuation with the Vietnamese sandwich, Như Lan remains one of the most popular spots in the city for foreigners and locals alike seeking that authentic banh mi taste.

I’d never tried a banh mi before visiting Saigon two years ago. But I fell in love with the city and the sandwich and never left. When a local magazine asked me to find the best in town, my bond with the ubiquitous street staple was forever sealed. For an entire week in 2015, it was pretty much all I ate, breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The floor of our apartment was covered in breadcrumbs, my notebook filled with flecks of coriander and errant tasting notes, the greasy smears of paté and mayonnaise still visible on its pages today.

Afterwards, I was contacted by a local food and beverage company to write the full history of the banh mi. Three months later, after contacting food historians in America and national libraries in France, after dragging Vietnamese friends to banh mi shops on the other side of Saigon with the promise of a free breakfast and the hope that their translation skills may solve one more piece of the puzzle, I filed a 10,000-word treatise on Vietnam’s sandwich of record. In the time since the manifesto, my appetite for banh mi shows no signs of waning.

I take a seat in Như Lan’s large dining area. The breakfast crowd has dispersed but the unmistakable early-morning aromas of phở linger, another of Như Lan’s offerings. A group of Western tourists crashes in, each clutching a banh mi. Their tattered copy of Lonely Planet gets splayed on the table. I know that book well, though it offers no more insight into the banh mi’s story than the obvious comparison to a French baguette.

France brought all manner of new and exotic items to Vietnam during its colonization of the region, from beer to bread, carrots to coffee, but didn’t hand them over willingly. The story of how the modern banh mi came together, the sort of banh mi you can pick up today at a farmers’ market in London, or from a food truck in Los Angeles, recounts 160 years of Vietnam’s history in one single, fiery package.

In unison, the visitors bite down into the bread’s fragile outer shell. A few fire off selfies as the customary explosion of crumbs covers the table. This is how all banh mi experiences begin. The bread gives way to the paté, then homemade mayonnaise, tender ham and cold cuts of pork. Pickled carrot and daikon add sweetness, cucumber brings a cool crunch. Cilantro. Unmistakable. A dash of Maggi Sauce for depth. Every taste bud gets hit. Then comes the chili, like a short, sharp slap in the face. “Wake up sunshine,” it says. “You’re in Vietnam now.”

Recognized by the Oxford English Dictionary in 2011, and the American Heritage Dictionary in 2014, the term ‘banh mi’ has officially entered the lexicon of the English-speaking world. But in Vietnam, it refers only to ‘bread’, or ‘wheat cake’, when translated literally. The pork, paté, and pickles combination now familiar to the West is known as a bánh mì thịt ngoui, ‘bread, meat and cold cuts’, often referred to as the bánh mì đặc biệt, ‘the special’, the one with everything. This is what every meat-eating traveler comes to Vietnam craving.

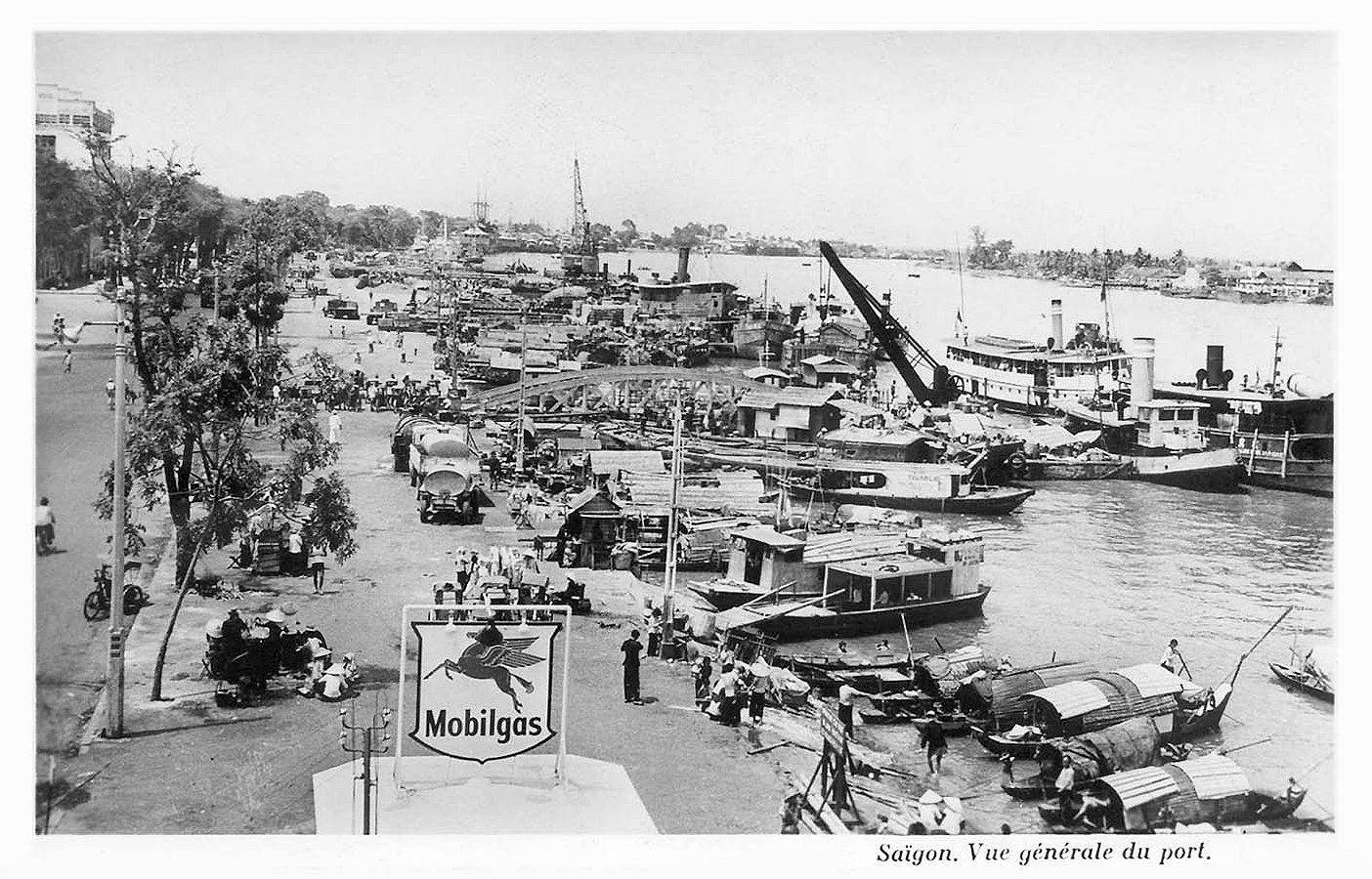

Như Lan may be an institution in Saigon, but the banh mi’s tale neither starts nor ends here. Its journey to international fame began 250 yards down the street, on the banks of the Saigon River in 1859, when the first French gunships and troops arrived to storm the city and begin the 30-year conquest of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, eventually forming the federation of Indochina in 1887. From here it would take another 70 years, two world wars, a long and bloody war with the French, the civil war that followed, and a young family fleeing the communist takeover in Hanoi to create the sandwich we know today.

When war broke out in Europe, the culinary boundaries separating French food from Vietnamese were shattered

By the early 1900s, Saigon’s grand, tree-lined avenues carried all the hallmarks of a fledgling European city, boasting ostentatious, neo-classical architecture, Parisian-esque cafes, and luxurious restaurants and hotels to serve the expanding population of colonial elites.

Not only did France use its wealth and technology to reaffirm and justify the colonial hierarchy and its assumed superiority over the Vietnamese, food formed another important line between ‘us’ and ‘them’. “Bread and meat make us strong, rice and fish keep them weak,” was a common adage at the time, backed by centuries of absurd pseudo-science which suggested that the rice-centric diets of Southeast Asia made its people somehow predisposed to imperial subjugation. And for a time the colonists stuck to it, rigidly, maintaining a European diet while disapproving of any French who ate Vietnamese food, and any Vietnamese who ate French food.

As an almost sacred component of French cuisine, bread became the foundation on which this notion could stand. The Vietnamese called it bánh tày, ‘Western cake’, an expensive foodstuff reserved solely for the foreigners. Wheat simply won’t grow in Vietnam’s climate, and the cost of importing flour made bread prices far higher than the average citizen could afford.

Baked long and thin, like the French baguette we know today, bánh tày were served in the classic French style, alongside a plate of ham, cold cuts, paté, cheese, and butter—a ‘casse croute’, as they called it, meaning to break the crust.

When war broke out in Europe, however, the culinary boundaries separating French food from Vietnamese would be shattered forever.

An elderly bread seller rolls slowly past on his bicycle, a basket of fresh rolls stacked high on the back and a crackly cassette recording looping out his call. “Bánh mì nóng giòn! Bánh mì nóng giòn đây!” ‘Hot crispy bread! Hot crispy bread here!’

Bread doesn’t last long in Saigon’s heat and humidity. For the banh mi shops that don’t bake their own, it’s not uncommon to see two or three deliveries like this arrive in the space of a morning.

The basket wobbles as he rounds the corner and his recording tails off behind the roar of Saigon’s seven million motorbike engines now tearing up the street. I check the address again. 511, Nguyễn Đình Chiểu Street, District 3, Ho Chi Minh City. Now a modern residential block, it was on this plot, in 1958, that a small family-owned snack bar known as Hoà Mã first appeared. The family left the premises in 1960, moving to another location just a few blocks away—my next stop—but it was here that the modern banh mi was born.

A few bridges had to be crossed before Hoà Mã’s owners could dish up the first truly Vietnamese sandwich. At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the two largest import companies in Indochina, being German-owned, were seized by the French colonial authorities—along with their warehouses piled high with European perishables. As thousands of French officials and soldiers stationed in Indochina set off to France to assist with the war effort, the Vietnamese market was suddenly flooded with a surplus of European products, all at discounted prices. The working classes were suddenly able to afford French beer, cheeses, meats, and bread, along with the now ubiquitous Southeast Asian staples of Maggi Sauce (a Swiss invention used as a savory flavor enhancer) and tinned condensed milk (destined to be a staple in Vietnam’s famously ferocious coffee).

For the 100,000 Vietnamese men sent to Europe to fight alongside the French, they too would get their first tastes of European food, much to the concern of some. Colonial authorities feared that having experienced ‘the good life’ in Europe, the repatriated Vietnamese would no longer respect the imperial machine. To some extent, they were right, and many returned to Vietnam with a newly acquired disdain for their French masters and a thirst for nationalism.

The First World War also ended the culinary xenophobia established by the first-generation colonists. As the global conflict disrupted shipping routes, a Vietnamese diet became unavoidable. Bread, however, was a hard habit to break.

With European wheat production in chaos, and the colony effectively cut off from the motherland, scientists Abel Lahille and Edouard Maurel convinced French authorities to approve the use of rice flour in the bread-making industry at home and abroad. Pain de riz was born. Rice bread didn’t last long—once the war was over, the substitution laws were quickly revoked—yet a modern-day banh mi myth survived: that its light and fluffy texture is a result of rice flour. Many 21st-century recipes outside of Vietnam continue to insist upon its inclusion to produce authentic banh mi bread.

“There are recipes that call for 50 percent rice flour, and they produce nunchucks that you could hurt someone with,” says Andrea Nguyen, a Vietnam-born food writer and chef, from her California home. “Rice flour does not rise due to a lack of gluten. Also, it will not brown beautifully. I have tried a couple of such recipes and they are terrible.”

In very small quantities, it is sometimes used to combat the effects of Vietnam’s humidity, but that trademark fluffiness comes from dough enhancers, commonly ascorbic acid, otherwise known as vitamin C, or pre-mixed industrial additives. Humidity and fluctuating temperatures are no allies when proofing bread. Enhancers have allowed Vietnam’s bakers to get consistent results from the very beginning while allowing for a little of that precious wheat flour to go a long way.

In the years between the First and Second World Wars, bread became more common in the Vietnamese diet. The French casse croute became the Vietnamese cát-cụt, as other food items associated with the meal adopted the Viet-Franco names still used today. Beurre became bơ (butter), fromage—phô mai (cheese), and jambon—giăm bông (ham).

Upon the invasion and occupation of Indochina by Japan during the Second World War, the Vietnamese were suddenly exposed to an efficient, modern, and emerging Asian empire that had, so far, defeated the major Western powers in the Pacific. The French military looked antiquated by comparison, fueling calls for independence as nationalist groups amassed throughout the country. In 1941, having returned from his sojourns in Europe, the Soviet Union, and China, the revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh established the League for the Independence of Vietnam, the ‘Viet Minh’, an anti-imperialist movement aimed at unifying Vietnam’s various nationalist factions and expelling the French and Japanese.

With the wartime revival of pain de riz, the French-inspired ‘cát-cụt’ of baguettes and cold cuts continued to be sold on Saigon’s streets to an increasingly Vietnamese crowd. As anti-French sentiment increased, though, the sobriquet bánh tày was dropped in favor of bánh mì, and butter was replaced with mayonnaise, a cheaper and more stable ingredient in Vietnam’s searing heat.

After Japan’s surrender in 1945 came the renewal of French control in Indochina. Nationalism surged, and in August of that year Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s independence, sparking a general uprising. By the end of 1946, the Viet Minh were at war with France.

Days begin early in Vietnam. The sun isn’t up yet, but already the alley is buzzing. When Hoà Mã’s owners left the shop at 511, Nguyễn Đình Chiểu Street in 1960, they came here, to 53 Cao Thắng Street, also in District 3. Little has changed since then, it seems. A group of workmen in gumboots and hard hats arrive on scooters loaded three men deep, taking seats at the line of knee-high tables stretched out in the open air along the side of the passageway. Even at five-thirty in the morning it’s a busy spot. Red-eyed taxi drivers clocking off, red-eyed taxi drivers clocking on, street sweepers, a few keen office workers. Through the pools of light from the overhead lamps runs a back-and-forth relay of staff to serve them.

There’s a simple menu and everyone is here for the same two things: a glass of cà phê sữa đá—Vietnam’s famous iced coffee rocket fuel—and a sizzling skillet of ham, eggs, paté, fried tofu, and a few crescents of onion. Then, on side plates, comes a parade of freshly-baked banh mi rolls, still warm from the oven.

This is Hoà Mã, in its second home, in operation here since 1960 when the owners Mr. and Mrs. Le moved their family and their business from Nguyễn Đình Chiểu Street. This is the family that invented the modern banh mi.

While the classic ‘special’ is still available, their focus now is on these aromatic breakfast platters, served, ironically, back in the traditional open French style, with fried meats, vegetables and tofu arriving on a sizzling skillet, the bread, homemade paté, mayonnaise and pickles then served separately on individual saucers. I head inside and on a chair in the corner sits an 80-something Mrs. Le. She’s watching her daughter, the current manager, as she whips up a batch of ten sandwiches to-go for a soccer team that just rolled up. Clearly age has done little to slow Mrs. Le; from her perch in the corner, she calls out instructions to her staff. “More paté. Less mayonnaise. Clean that table. Bring me coffee.”

The Le family came from Hoà Mã, a village now swallowed up in the sprawl of Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital and Saigon’s northern counterpart. As Ho Chi Minh’s war with France continued in the countryside, Mrs. Le had worked for a French-owned company in Hanoi, supplying European-style hams and processed meats to French restaurants. In 1954, when France agreed to end hostilities and divide Vietnam in two, with Ho Chi Minh’s communist government taking power in North Vietnam and a US-backed capitalist Republic in the south, the Le family fled Hanoi and traveled to Saigon.

They called them the Bắc 54, ‘the Northerners of 1954’, the estimated one million Vietnamese who escaped the communist stronghold before the border was closed. Behind them, as communism took root, private enterprise was banned, French businesses seized, and ration cards distributed. Restaurants, cafes, even mobile street vendors, all disappeared, and the evolution of the banh mi was passed to Saigon.

Using the skills and recipes she’d learnt from the French, Mrs. Le began producing her own processed meats, eventually opening a cát-cụt shop in Saigon’s District 3, naming it, of course, after their village. The most popular banh mi shop in Saigon at the time was called Vinh Loi, located on present-day Le Loi Street, a tree-lined boulevard in the city center. But, like the street on which it sat, Vinh Loi was only for the wealthy.

Taking a brief moment to chat between orders, with Mrs. Le now resting upstairs, her daughter Hanh tells me how her father made the banh mi affordable to everyone. “He reduced the size of the traditional baguette to around 20 centimeters,” she says, through an interpreter. “He also reduced the amount of meat, adding vegetables instead.”

With a steady stream of students, laborers, and office workers visiting their new shop, Mr. Le noticed that many did not have time to sit down and eat. “So he began placing the cát-cụt ingredients inside the bread,” says Hanh, “so people could take it with them and eat on-the-go.”

Hoà Mã’s bread rolls sit in huge trays waiting to be cut and stuffed, and I put the rice flour theory to her as she begins preparing a fresh order.

“Duck eggs,” she says. “That’s what my parents used as their dough enhancer, although we use chicken eggs now.”

So do they use any rice flour at all?

“She won’t say,” says my interpreter. “Secret recipe.”

When the second Indochina War began in 1955—known to the West as the Vietnam War—life in Saigon continued more or less uninterrupted. Hoà Mã moved to its present home in 1960 and news of its sandwiches spread. Of course, it would be unfair to say that the Le family was solely responsible for the banh mi we know today. But Saigon’s oldest vendors, Như Lan’s owner included, still point in their direction when asked where ‘the special’ came from.

With Hoà Mã at the epicenter of the banh mi revolution, vendors all over Saigon began copying, borrowing, stealing, and improving on each other’s recipes. “In the south, they lived large,” says Andrea Nguyen, “so a lot of stuff was added, like fresh herbs, vegetables, and pickles.”

When Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese Army in 1975, a reunified, wholly communist Vietnam entered a decade of austerity, poverty, hunger, and hardship. Private businesses like Hoà Mã were temporarily closed and the banh mi torch handed to those who had fled Vietnam’s shores. Many, like Nguyen’s family, arrived in California.

From the West Coast, the banh mi—along with its cousin, phở—began a crusade across the States, and, with a little help from Western food writers, travel journalists, and a growing number of tourists returning from Vietnam with tales of its culinary delights, the banh mi became one of the world’s favorite sandwiches. These days, you can find banh mi on sale in strip malls and food trucks from Memphis to Munich.

In Ho Chi Minh City today, following the large-scale economic reforms of the late 1980s, the Đổi Mới, which brought a freshly modernized Vietnam out of the darkness of the post-war period, the banh mi has re-established itself as a centerpiece of the city’s culinary lineup.

Helped, in part, by the banh mi’s success abroad, the old-school curbside vendors are still thriving, especially those around the tourist hotspots of District 1. Bánh Mì Huỳnh Hoa is regularly touted as the best in the city by foreign guidebooks and food bloggers. It’s good, no doubt about that, but its reputation is built more on the sheer volume of meat piled into its rolls than the quality of the sandwich’s overall construction. A far more refined, far more ‘Vietnamese’ banh mi can be found nearby at Bánh Mì Hồng Hoa. Their bánh mì thịt nguội remains my favorite sandwich in Saigon.

Despite a large local following, tucked down an otherwise unassuming side street, the English menu pinned to the front of Hồng Hoa’s counter proves they know what the tourists want, offering the classic fillings alongside more modern creations such as the bánh mì chà bông, filled with pork floss (a dried pork ‘cotton candy’), or the bánh mì xiu mai—essentially a Vietnamese meatball sub. If the latter sounds like your kind of sandwich, try Bánh Mì 37 close by (forming a triangle of three of the city’s best banh mi sellers, all no more than five minutes on foot from each other). This simple food cart, wheeled out each day at 5 pm onto busy Nguyễn Trãi Street, serves a superlative banh mi filled with freshly barbecued pork patties smothered in a sticky barbecue-style sauce.

The banh mi is already considered one of the best sandwiches in the world. Why mess with that?

Vietnam’s street food is a cultural commodity that attracts thousands of hungry tourists each year, and it’s no surprise that the long lines of bodies forming at vendors like Bánh Mì 37 and Huỳnh Hoa are more frequently punctuated with foreign faces. But as Vietnam’s middle-class grows, as its increasingly cosmopolitan society looks to get off of the sidewalk and into clean, ‘Western-looking’ establishments, a new generation of banh mi outlets are beginning to emerge.

Having arrived in early 2016, Bánh Năm—năm meaning five for the number of different sandwiches on offer—is one example of the new guard. By retaining the best of what an authentic banh mi should look and taste like, while giving its preparation and presentation a 21st-century makeover, this clean and stylish concept looks set to become the start of the next generation of banh mi outlets in Vietnam.

With low prices, clean white walls, colorful signage, backlit menus and an open kitchen, Bánh Năm’s outlets have been a hit with the locals, a small but important taste of New Saigon, but there’s only one twist: it is by a European.

“Our idea is simple,” says Dutch co-founder Timen Swijtink. “Do not change what people love. The banh mi is already considered one of the best sandwiches in the world. Why mess with that? What we want to work on is bringing a hint of modernity, through cleanliness, convenience, and consistency.”

Like the Bangkok of the 1990s, Saigon is transforming into a connected, round-the-clock, ultra-modern metropolis. Bánh Năm’s social media presence, local delivery service, and 24/7 opening stand in stark contrast to the ‘mom and pop’ vendors like Hoà Mã, those that appear for just a few hours each morning or afternoon.

“We are the next, albeit small, headline in the story of the banh mi,” adds Swijtink. “We want to make it available cheaply, to the masses, in a clean way, so nobody has to worry about getting sick.”

Swijtink is referring to the frequent lack of refrigeration at the more traditional street outlets in Saigon, with cooked and uncooked meats often left in the open, or, at best, sealed away yet still exposed to the country’s tropical temperatures. While getting “sick” is rare, given the quick turnaround time and sheer freshness of the ingredients, the ever-present threat of food poisoning is something the Vietnamese authorities have been making attempts to address recently. They have banned street vendors in some areas altogether, while in others, they provide dedicated locations with refuse facilities, running water and waste, alongside a program of food hygiene training.

For the camera-wielding tourists, shops like Bánh Năm may represent too large a leap from the authentic street food experience, void of the motorbikes buzzing past an inch from your back, void of the toothy grin from the octogenarian owner as she makes your dinner in her pajamas, or the old men and their coffees shooting the breeze. But for the new generation of educated, middle-class Vietnamese, with the latest iPhone in their pockets and their eyes set on making a name for themselves, they offer something far more paramount: they offer the future. The future they’ve been watching on American TV for the past 20 years, the future they’ve heard about from their cousins overseas, and the future where buying your banh mi from this shop instead of that one can give you a small measure of status, and maybe even an edge over your competitors.

It’s early afternoon and I’m riding towards Bánh Năm’s outlet in Binh Thanh District, a short hop over the canal from District 1. The rainy season is here and the grey fists of storm clouds are tightening overhead, threatening a deluge that will turn this road into a river in seconds. There’s a tremble of energy that resonates through Saigon’s already frenetic two-wheeled traffic at times like these, everyone thinking, can I make it there before it starts? Can I make it there and back? And we all unconsciously pick up the pace.

The shop’s glowing yellow sign appears like a beacon in the falling light, the sky about to drop. You can already smell the rain.

“Một bánh mì thịt,” I say, ordering their faithful rendition of ‘the special’. Homemade paté, a smear of mayo, a long ribbon of cucumber, then ham, pork roll, carrot and daikon. Despite the modern trappings, Bánh Năm offers a faithful rendition of the type of sandwiches Hoà Mã have been serving for 60 years. But there’s still room for the new, of course, with grilled chicken, grilled pork and even a vegan-friendly grilled tofu option (made with vegan paté, no less), finding equal space on their menu. After drawing a generous line of cilantro from one end to the other, the young girl stops, looks up, clocks the foreigner.

“Chili okay?” she asks.

Follow Simon’s Banh Mi Trail:

Như Lan, 50 Hàm Nghi, District 1

Hoà Mã, 53 Cao Thắng, District 3

Huỳnh Hoa, 26 Lê Thị Riêng, District 1

Hồng Hoa, 62 Nguyễn Văn Tráng, District 1

Bánh Mì 37, 37 Nguyễn Trãi (at the entrance to alleyway 39), District 1

Bánh Năm has 3 locations across HCMC. Visit banhnam.vn for details.