What happened when a photographer ask an entire battalion in Western Sahara to collaborate on a conceptual art project.

So many photographers and journalists have embedded with combat units in Afghanistan since 2003 that the country has earned the nickname “Embedistan.” A controversial (albeit not new) practice, some believe that embedding serves the military above all, giving them an extra tool in their war for information and opinion. But what happens when a photographer truly collaborates with an army? Simon Brann Thorpe worked hand-in-hand with a military commander in Western Sahara and his troops to develop his conceptual photography project, “Toy Soldiers.” The relationship depended on trust and a willingness to invest oneself in the artist’s vision. The result is an exceptional body of work, which will be presented to the public this week for the first time during Photo London. The book “Toy Soldiers” will be published in June and is available for pre-orders now. Simon Brann Thorpe joined R&K from London.

Roads & Kingdoms: Why set this project in Western Sahara?

Simon Brann Thorpe: In 2004, I did a project about landmine victims there. It was my first project to try to bring awareness to the issue of landmines, which are as invisible in the area as the conflict itself–both physically and metaphorically. That was what introduced me to the bizarre, absurd nature of the conflict and how and why it’s remained invisible for so long. Fairly soon after that, I knew I wanted to go back. But I didn’t want to cover the conflict with traditional reportage, I just didn’t think it would do it justice. Something that has been so invisible isn’t going to become suddenly visible with the regular means of communicating those issues. So it took me a while to come up with the way I really wanted to express the situation and my own narrative on war. The concept was born in the shower one evening.

R&K: Did you play with these toys when you were young?

Thorpe: I had Action Man but I didn’t have toy soldiers. But like any boy who grows up in the West, I found war games fun and exciting.

R&K: These particular plastic army men are American toys I believe.

Thorpe: I think probably. Certainly in America artists have been playing with the narrative of toy soldiers for a while now, using the actual toys in projects. The commercialization of war and its glorification is a pan-Western thing, but perhaps it’s a little more obvious in the States through Hollywood and the merchandizing of war. It’s interesting because it’s also very much part of what I’m calling the meta-narrative of the project, the whole aspect of war gaming and desensitization to war that begins as children. The project is surprisingly multi-layered, and I’m finding that out as more and more people see it.

R&K: What about the soldiers you worked with, had they ever seen these toys before?

Thorpe: Probably not. I took toy soldiers out with me on the first few meetings that I had with the military commander so he would have a visual reference to what I was trying to achieve and the narrative that we were playing with. I actually didn’t ask whether they’d ever seen them before, but no one picked them up as some sort of bizarre curiosities. I’m guessing they were probably somewhat familiar.

R&K: So this commander, he was the person who made all of this possible on the ground, right?

Thorpe: Yes. He’s a refugee like all the other Sahrawis divided by the conflict, and the commander of a particular region of the area they call Liberated Western Sahara. I think the most important thing for him was my credibility as an artist and in what the project was trying to achieve, and then on a secondary note, that he completely related to the concept through his own experience. As custodians of this little stretch of land, their existence within this conflict without end and at the mercy of other people’s decision-making is something that resonated through the concept. That sort of powerless position.

R&K: Can you talk about your process? It seems like this took a huge amount of planning, how did it take place on the ground?

Thorpe: In terms of the production of the images, what we had to do first was produce the bases to stand on. I wanted to have the soldiers physically act out that stance on the base rather than to add it in post-production because that enactment is an important part of the credibility of the project. So we made them out of old oil drums, which we covered in paint and in sand until they were ready to basically be carted around to each location. The soldiers would carry them in the heat and cut their fingers on them and all that kind of stuff. It was a real process for them and for me to getting it all right. But it was an interesting experience and that one that I’ll never forget in terms of the willing participation of the soldiers in this project. It was amazing and very humbling.

R&K: The entire project depended on that participation. If they hadn’t understood the project or been interested, you couldn’t have gone through with it.

Thorpe: Yes, totally. I would have the military commander stand next to the camera and I would say what I needed and where I needed them to go. He would shout the orders over the top of the camera and these guys would go into whichever position they needed to be in. It took time and it took patience and it took proper planning. All the major landscape shots were scouted and storyboarded a long time before we went out to produce the images. It had to be that way.

R&K: You spent some nights out in the desert between shoots with the soldiers.

Thorpe: Yes, most nights actually. We were shooting for about five weeks, so we probably spent three and a half to four weeks sleeping out in the desert. I would spend most of these nights listening; I was just a fly on the wall. They have an incredible sense of humor and I’d just pick up the vibe of the conversations and would make a few comments that were translated. It was just a little bit of life around the fire really. They would make bread in underground ovens and cook lamb for a couple of hours and we’d all eat and go to sleep. It was an extraordinary experience. The range of soldiers was quite wide, from 18 to 80 almost, so I got a cross-section of very human responses and comments and humorous gestures and everything in between.

R&K: The idea of this army in the middle nowhere taking the time to complete a conceptual art project with you seems almost absurd, is that the right way to describe it?

Thorpe: I think that for me, the situation there is what’s absurd. I’m not sure I would describe soldiers taking part in an art project like this as absurd myself. But I’ve never seen anything quite like it before, this collaboration and trust between a military commander and an artist. I struggled at times internally with what I was asking them to do, how that would make them look, how that would make them feel and all of those struggles you have as an artist, justifying the credibility of your work. But I had to believe in what I was doing, and ultimately they did as well.

R&K: The trust is very apparent throughout the project, they really invested a lot of themselves in it.

Thorpe: Totally. I came with a budget to assist in the manufacture of the bases and to go towards some food and fuel and that kind of thing, but apart from that, it was totally voluntary. Everything was given to the project on the basis of trust, and a belief, quite a maverick belief from the commander, in the narrative of what we were doing through the realms of contemporary art.

R&K: Does his belief in the project stem from the fact that the world forgot about this conflict?

Thorpe: That’s the meta-narrative of the project, war games in general and how images of war are digested and consumed. Especially now in the digital realm, which is ravenous for content but short on attention span. What are the consequences of ubiquitous images of suffering? Do they desensitize an audience? How do you communicate an invisible issue, an invisible conflict that nobody cares about? I think it speaks from any conflict nowadays in how you’re getting that message across, because I think traditional reportage portrayals of war just fall on deaf ears. The reality for these soldiers is that they ended fighting in 1991 and there’s been a UN-monitored ceasefire ever since, which was agreed to on the promise of a referendum that simply never happened. I can only imagine how the commander feels, trapped in the reality of that situation where tens of thousands of people have been waiting on a promise. I can only imagine. I think it was just a sort of instinctual belief, as much for him as it was for me, that this approach has a lot to say about war.

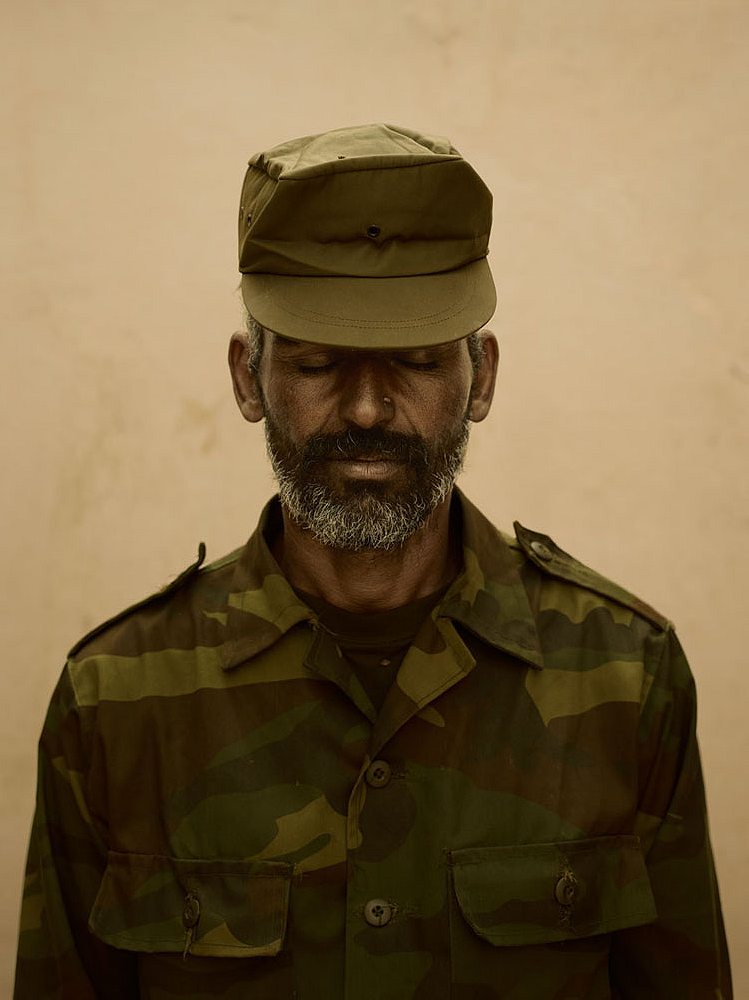

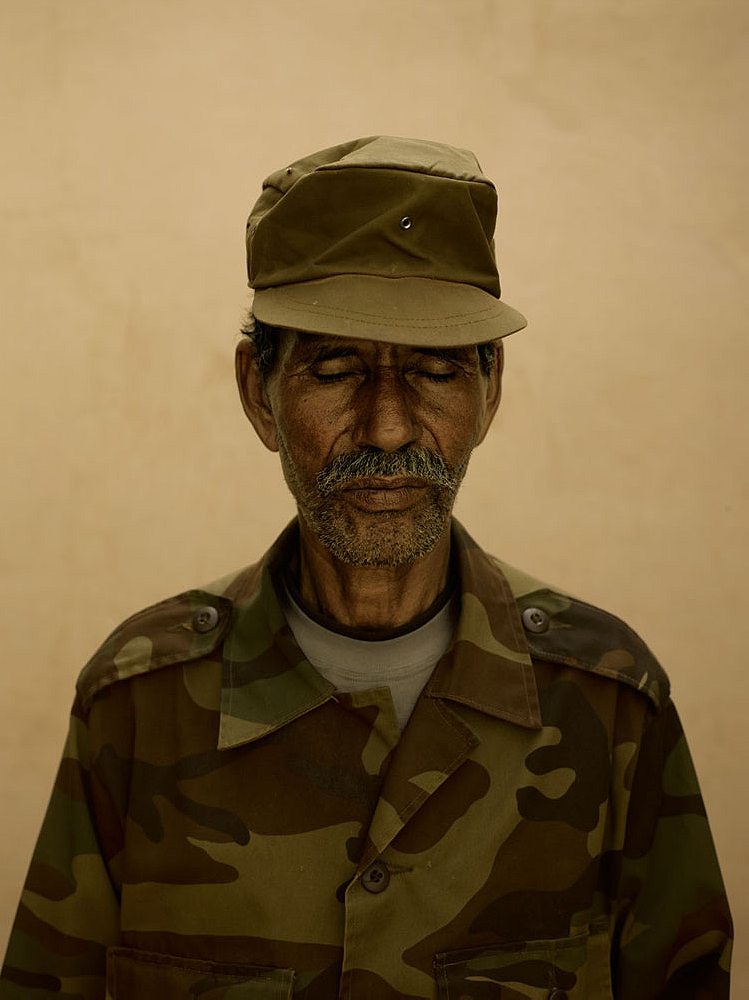

R&K: Can you talk about the portraits included at the end of the book, where the soldiers have their eyes closed?

Thorpe: The project on the whole is based in three chapters. First you have landscapes, and then each consecutive part zooms in. But really at the heart of this project are individual human beings and the fragility of human flesh within war. So I wanted to end on the humanity trapped within this invisible conflict and so the portraits were a narrative on that. The eyes closed were further narrative on their invisibility, on their impotence really not just as soldiers but also as refugees, and what a powerless position that is to be in.

“Toy Soldiers” will be shown during Photo London this week and Simon Brann Thorpe will be signing books at Somerset House on May 23rd. You can purchase advance copies of the book online.