A photographer documents the lives of a lesbian couple in Putin’s Russia, in all its brutal intimacy.

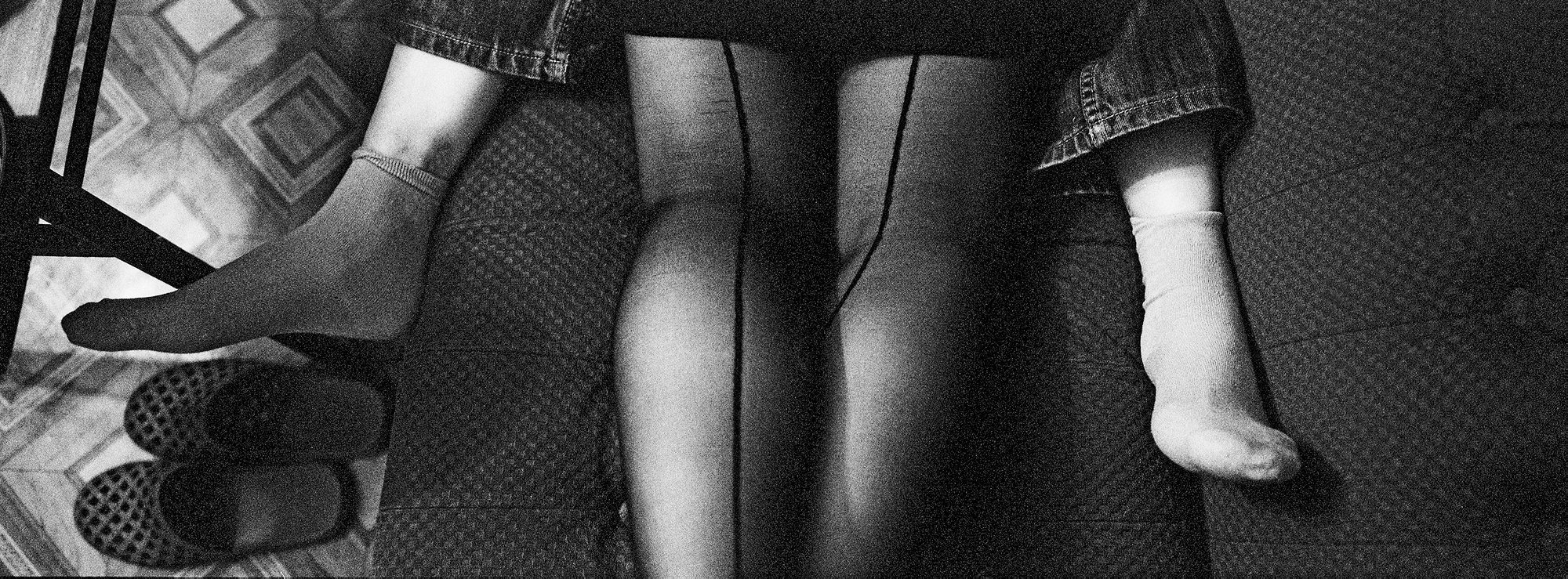

Last month, Misha Friedman flew to Russia. He bought a bottle of champagne from the duty free shop at the airport and asked his friends Lyudmila and Natasha to meet him in Saint Petersburg. It was a big occasion. After three years of photographing the couple, he was finally showing them the book he had made about their lives. The two women had not seen a single photograph until now. Flipping through the pages, they relived the blissful and painful moments, some forgotten and others still raw, that shaped their relationship throughout the years. “Russian Lives” is part of a series launched by The New Press that will look at LGBT lives across the world through photography. An intimate and brutal look at love, Friedman’s book also includes a powerful introduction by Jeff Sharlet, who received a National Magazine Award last week for his reporting on the LGBTQ community in Russia. R&K met up with Friedman shortly after he returned to New York.

Roads & Kingdoms: How did Lyudmila and Natasha react to the book?

Misha Friedman: It was an emotional moment. They were happy, obviously. Imagine someone photographing your life for years and you not seeing a single image from it. So it was just special and nice, but we also talked about what this book can mean to them. Who knows what people’s reactions will be? It’s also about me and the publisher taking some responsibility for them if something does happen.

R&K: Will “Russian Lives” be sold in St. Petersburg?

Friedman: Well, it’s released worldwide. I doubt the publisher has specific plans to market it in Russia given the current political climate, but it will be on Amazon. Theoretically, it’s not against the law to sell this book in Russia. I think as long as it’s not within, I don’t know, 100 feet of a school. But I have no idea if that will happen.

R&K: Could the book’s release have an impact on you working there?

Friedman: Probably. It depends on what I want to do. It may have an impact if I chose to photograph, I don’t know, the World Cup or Kremlin stuff. Basically, if I need official authorizations. But who knows? All of this was huge before Ukraine became the story, and now they have a new villain. It’s like, gays were the Jews for a year, and now there are new Jews and new scapegoats. There are so many religious fanatics who feel empowered to act on their own because of what the government is saying or not saying.

R&K: When did you meet Lyudmila and Natasha for the first time?

Friedman: I met them in November 2011. I was doing a story about something else. The art director for this book had given me an idea for a project in Russia and he asked me to be on the lookout for an interesting gay couple. The larger idea behind this project was thought of when gay marriage was legalized in New York. The idea was to do something for the gay community here, and as a point of reference, we thought about The Family of Man, a photography exhibition that was organized by the MoMA 60 years ago. In that exhibition, it was shown that the arc of life is a heterosexual relationship. So we thought about a collection of stories from around the world that showed that life is different. As the project grew, we decided that each country would become a separate chapter. So, “Russian Lives” is a chapter.

R&K: How much time did you spend with Lyudmila and Natasha?

Friedman: Honestly, I don’t remember anymore. But altogether, it was probably about a dozen different trips. Some were for a day, others for a week. Overall, I’d say about a month of shooting days. And it was shot on film, digital, panoramic, everything. That’s why you have all these different formats, because I really didn’t have funds to go to Russia and be with them for days or weeks at a time. So it was always like, I’m shooting a project about this and that’s the equipment I happen to have in Russia at the moment.

R&K: The book documents a tumultuous relationship – are Lyudmila and Natasha still together today?

Friedman: Yes. I mean, they have their ups and downs. A year into the making of this project, I arrived and they had split up. They hadn’t told me ahead of time. But by then I already had a good thing with them, so as you see in the book, they let me photograph them with their new partners.

R&K: You didn’t think of ending the project at that time?

Friedman: I just thought, that’s life. Just because these photos will be published into a book format, it doesn’t mean that my relationship with these people has to end. So in a sense, it’s not that important. What is important to me is my relationship with them as friends. And that’s going to continue regardless of how the book is received or not received.

R&K: It’s really powerful to read the short interviews at the beginning of the book, because you conducted them when they had split up…

Friedman: This was by chance. The art director and I wanted to do interviews and we came up with questions ahead of time. It just so happened that on this particular trip, Lyudmila and Natasha were separated. It was weird to be the only one hearing both sides, and of course, they were both curious about what the other one said, but I couldn’t tell them.

R&K: Was it a difficult story to tell, as a man?

Friedman: Actually while I was doing this I had a few assignments to photograph gay men. As a heterosexual man, the “Russian Lives” project was much easier. [Lyudmila and Natasha] felt comfortable. Even when I was very close to them, it was never ambiguous, like, where is this going? I had a conversation with an editor at TIME, who, when he saw my work on gay men in Russia, said he didn’t feel the closeness that he’d seen in the “Russian Lives” project. And I said, well, it’s because when I’m with them, no one is massaging my back.

R&K: There is only one political protest included in the book, and it’s in color…

Friedman: Yes, I happened to have a digital camera that day. It was a summer day in St. Petersburg, the event was symbolic: they were throwing balloons in the air in solidarity with the LGBT community. And then religious people… activists, that’s the word… religious activists showed up and neo-Nazis showed up. It got very ugly. At that event, what was interesting was that the balloon-throwing ceremony was sanctioned and the police probably had intel that neo-Nazis would come, so the police were guarding the protestors. If this had been a non-sanctioned event, the same riot police would have beaten up these protestors.

R&K: Is St. Petersburg a bit safer that the rest of Russia when it comes to the LGBT community though?

Friedman: If you’re from a small town and you have questions about your sexual orientation, Moscow and St. Petersburg are the places you escape to because they are larger cities and there’s more going on. There are larger online communities there and parties. But at the same time, this whole anti-gay thing was started by a politician who is from St. Petersburg. It’s always been a hotbed for Russian fascism, even during Soviet times. The most organized, most violent soccer hooligans are from St. Petersburg. So it’s more of a mix.

R&K: You say that it was a rare decision by Natasha to go and protest. The two women aren’t really activists.

Friedman: No. Not everyone is Harvey Milk and not everyone wants to be. It’s just dangerous. You don’t want to get beat up when you’re in your thirties and you have a job, a life, kids… You weigh everything: what are you going to achieve by releasing balloons versus getting your face smashed?

R&K: It’s even more impactful, I think, that the focus is on two women trying to live regular lives.

Friedman: Yes. That’s why you don’t see 50 pictures form the protest. They were happy when they went out and they had money to spend. They were not happy and were fighting when they had to move because they were broke.

R&K: Just like everyone else.

Friedman: Exactly.

R&K: You photograph them in very intimate moments. What is it like being in the room for that?

Friedman: I think they didn’t know what to make of it at first, because it’s not common to have your picture taken and never see it. And if it happens again and again, I think you go through this process where you’re first not sure what to make of it, then you’re a little bit mad that you don’t get to see it, and then you just give up and accept. It comes to a point where you just get bored, and that’s when photography really begins: when they get bored and they don’t see me anymore.

R&K: Natasha is a photographer. What role did this play in the project?

Friedman: That’s how we met. Someone told me about her because she was interested in photography. It actually made it easier to photograph Lyudmila, because as a photographer’s girlfriend, she was comfortable with her picture being taken.

R&K: How did the situation change in the three years you were documenting their lives?

Friedman: When I started, this Vitaly Milonov was a local [anti-gay] councilman who was trying to get something done on a local level. He was not taken very seriously. So this went from him being the local clown to “Holy shit, no way this is becoming a law in St. Petersburg!” to “Are they really going to make this into a federal law?” to “Are they going to prosecute?” to “OK, the Kremlin moved on to other stuff with Ukraine.” The law still exists on paper and from time to time you hear of a teacher being fired here, an activist losing his eye there. People suffer, people get attacked. These laws can be used against anyone at any given moment. If someone discovered this book in St. Petersburg tomorrow, there is no reason they could not alert the authorities about it.

R&K: Are you a little bit hopeful that things will get better?

Friedman: No. I’m not hopeful. It’s hard to cover Russia and know this region as well as I do and be optimistic about anything. I’m hopeful that this book will mean something for Lyudmila and Natasha, but Russia overall is not giving a lot of reasons to be optimistic these days.

R&K: Did you have a particular connection to the LGBT community?

Friedman: Not when I started. But this helped me do a better job since. When I started spending time with Lyudmila and Natasha, that got me thinking about what life was like in provinces, so I did that. And then I did a story in Crimea. This project helped me become a better photographer because most of my other work is misanthropic, and from tuberculosis to corruption, it’s this-is-not-going-to-end-well work. This helped me stay sane.

You can buy “Lyudmila and Natasha: Russian Lives” here.