Meet the people keeping the Lone Star State safe from cattle rustlers.

A red Ford pickup eases down a narrow, dusty road in the heart of Texas Hill Country, about two hours west of Austin. As he drives, an aging rancher named Buddy Wells gestures toward the grove of cedar elms lining the road. That was the last place anyone saw his cattle.

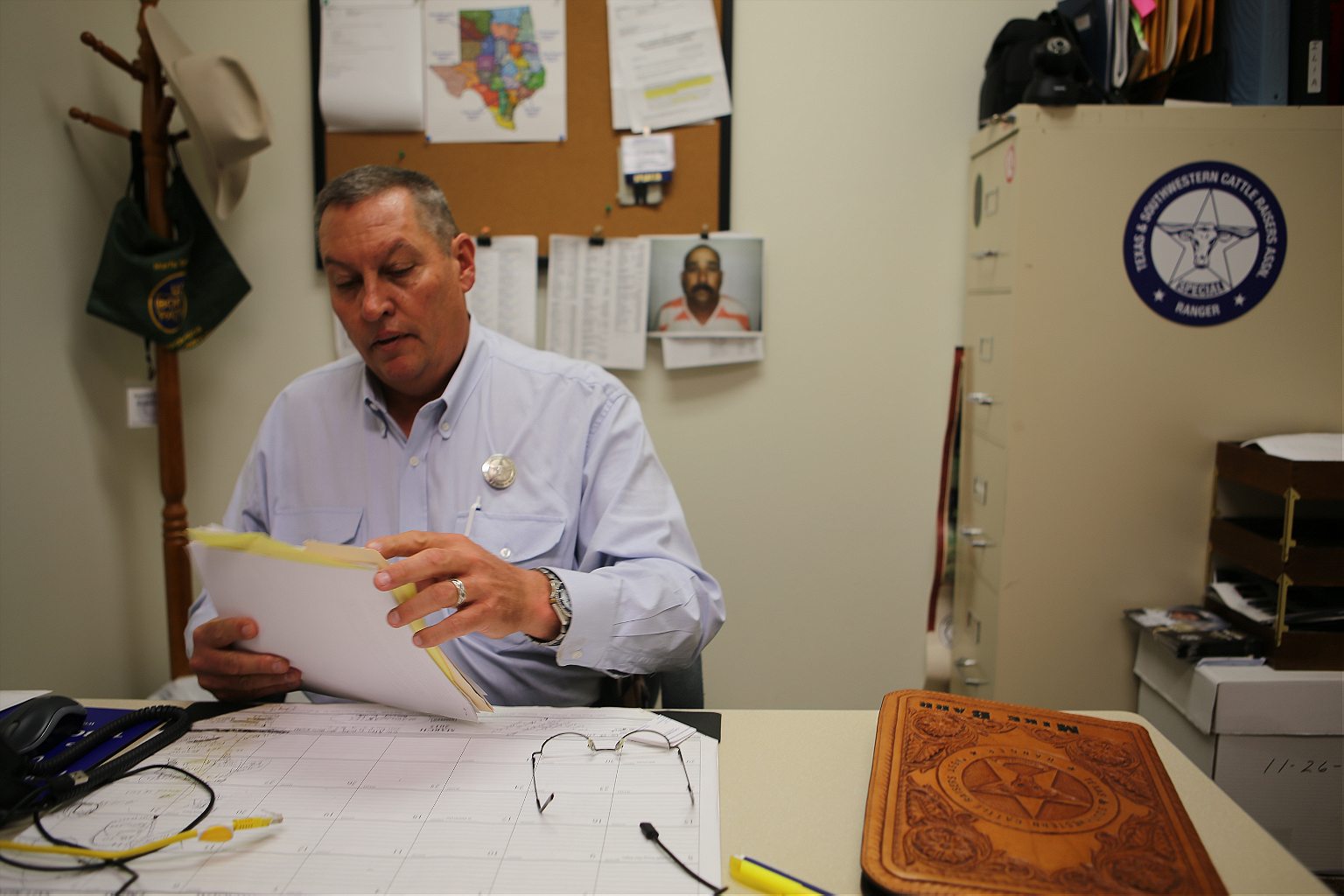

It’s mid-morning on the outskirts of Medina, Texas, a small, unincorporated community in Bandera County. Wells has enlisted the help of Mike Barr, one of the 30 special rangers working for the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association. They are commissioned peace officers who investigate agricultural crimes, primarily cattle theft, or “cattle rustling.”

It’s been more than a century since gun-slinging outlaws roamed the badlands of Texas. However, even though frontier bandits—from the likes of the Sam Bass Gang to John Wesley Hardin—no longer plunder stagecoaches or make their getaways by horseback, some things haven’t changed.

In a place where beef is the economic lifeblood of many families, the rustler remains the bane of ranchers. In 2014, the special rangers recovered or accounted for nearly 4,000 head of cattle, worth about $4 million. They also recouped millions of dollars worth of other livestock and ranch-related property. This year alone, the rangers have recovered close to 5,000 head of livestock.

Texas is steeped in both the myth and the reality of cowboys and cattle rustlers. Some of these stories are fueled by over-the-top Hollywood Westerns, but others are grounded in historical accounts. It might seem like a strange link to the past, but cattle rustling is just as real in the digital age as it was during Reconstruction.

In late June 1870, in the humid, coastal marshlands of southeast Texas, a posse of vengeance-seeking ranchers surrounded a house belonging to a freed slave named Joe Grimes. They suspected a gang of horse and cattle thieves, Grimes among them, had holed up inside.

The gang, led by a group of brothers named Lunn, had been slaughtering stolen cattle and selling their hides to unscrupulous buyers, according to Flake’s Bulletin, a weekly newspaper out of Galveston. Locals along the Tres Palacios River reported finding piles containing as many as 800 of the butchered animals. In some cases, these death heaps consisted of only the charred remains of bovine skeletons.

Despite having warrants out for their arrest, the Lunn brothers had managed to evade the Matagorda County Sheriff, so the ranchers took matters into their own hands. Just a few days prior, the citizen posse caught four of the gang members and hung three of them on the spot.

Now the posse closed in on Grimes’ house, where they expected to find at least one of the Lunn brothers. A posse member by the name of Edward Anderson stepped closer, demanding the door be opened. A voice from inside answered: I’m just getting out of bed. I’ll open the door when I get some clothes on. Suddenly, the end of a double-barreled shotgun emerged from the window and blasted Anderson straight to his grave. The posse unloaded a barrage of gunfire. Inside, they found only the body of Joe Grimes, perforated by 14 bullet holes.

Cattle ranching is in the marrow of Texas identity. The practice stretches back to the early 1700s, when herds of livestock were used to feed Spanish soldiers and missions. By the latter half of the 19th century, cattle ranchers could be found in almost every corner of the state and on either side of the Rio Grande. Today, Texas is the top cattle-producer in the United States, with cash receiptsreaching $10.5 billion in 2012.

Today’s cattle thieves and the men who pursue them no longer inhabit the anarchic Wild West of vigilante justice, but the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association and its special rangers trace their roots back to that time. In 1877, just 32 years after the Republic of Texas was annexed by the United States, a group of cattlemen in North Texas founded the TSCRA with the primary mission of preventing cattle theft.

Special rangers are the law enforcement wing of the TSCRA. They operate throughout Texas and in some parts of Oklahoma, and are commissioned as peace officers by those states. While they have the full power of the law, they are not paid for by taxpayers but by the TSCRA member base of more than 17,000 ranchers and businesses.

Over the past several years, their work has been increasingly defined by changing weather and climate patterns: severe drought in Texas has cut down the size of cattle herds, and that reduced supply has given rise to record high beef prices. Under such circumstances, cattle theft has become an ever more lucrative calling for modern-day outlaws.

In many cases, those cattle are recovered when they go up for sale, says Barr. Rustlers often take the cattle to a livestock auction in a different county or state and sell them for full market price, which is currently somewhere between $1,500 and $3,000 for a single beef cow. If they don’t sell their haul, the thieves can always butcher the stolen cows.

Cattle theft is a felony, and thieves in Texas face serious jail time. No one is hung for cattle rustling anymore, but some have been sentenced to 100 years behind bars.

Today, Wells and Barr wind around the country roads, looking for any indication of what might have happened to the missing cattle. They turn off one back road and into a Christian summer camp, wondering if the rustlers made their escape through the campgrounds.

Barr ponders the puzzle before him. He was recently transferred to the area and is still getting the lay of the land. Most of this morning’s drive involves the men pointing out landmarks to each other. (There’s the creek along the tree line. That’s a new bit of barbed wire fence. A newcomer just bought that property. There’s the dirt road we traveled down earlier in the morning.)

TEXAS CATTLE RANCHERS FEEL THAT THEIR LONG-LIVED TRADITIONS ARE THREATENED

For this investigation into Wells’ eight missing head of cattle, all of the work is done from inside the truck. There are no posses or double-barreled shotguns; it’s much like any other plodding police work. It involves driving, making phone calls, more driving, then observing, and maybe stopping to knock on a door or two to look for witnesses.

After a few hours, the men drive back to town, and Wells and Barr reminisce about the cattle-ranching days of their youth, when one or two big ranches stretched for thousands of acres and cowboys were living on the land.

“I grew up on a farm, a ranch, so I’ve been around livestock all my life,” Barr says. “Raised in it. Lived it. Loved it. It’s just a good way of living. And doing this, as far as law enforcement, you’re dealing with the best people.”

Those people—Texas cattle ranchers—feel that their long-lived traditions are threatened by a multitude of forces, from “big government” to lowly cattle rustlers. Barr sees himself and the other special rangers as defenders of the ranchers and their way of life.

Cattle rustlers aren’t your run-of-the-mill criminals. They often have some cattle ranching in their blood, says Larry Gray, TSCRA executive director of law enforcement.

“They’ve had some exposure to the cattle industry some time in their lifetime. They were raised on a farm or ranch, their grandfather had a farm or ranch where they learned how to handle cattle, how to load cattle, burn a mark in ‘em,” says Gray. “So it’s not a crime that a novice really commits. You couldn’t just wake up one day and decide ‘I want to be a cattle thief,’ and go out and steal cattle. You just wouldn’t know how to do it.”

Armed with the requisite industry know-how, cattle thieves are able to look for patterns and habits that make some ranchers easier prey than others. If a rancher feeds his cattle at the same time every day, for example, then a watchful thief will make note and load up the cattle when he knows the rancher won’t be around.

And legends of the cold-blooded rustler behavior persist outside of old Western novels. “I hate to say this, but I’ve heard some people have cut the tongues out of dogs so they don’t bark, so they’re not heard,” Barr says. He adds that, with only the moonlight to guide them, the rustlers will use their silenced canines to round up the cattle into a trailer, before fading into the darkness of the Texas night.

Back on the case of Buddy Wells’ missing cattle, Barr stops by the constable’s office in Medina.

The front desk clerk says the constable is out. Barr hops back in his truck and drives off toward the sheriff’s office just outside the nearby town of Bandera.

His white Ford F-150 curves alongside the tree-speckled hills carved out by the highway. He stops and pulls a U-turn. He just passed the constable on the side of the road.

Constable Don Walters is dealing with what appear to be some foreign tourists and their tattooed, city-slicker guide. As soon as Barr rolls up, Walters sends the out-of-towners on their way.

The men chat unhurriedly in the heat of the sun. They are clad in the perennial garb of Texas lawmen: straw cowboy hats casting a constant shadow on their faces, button-down shirts, shiny belt buckles, blue jeans, and boots. They each carry a handgun in a leather holster on their belts and sport silver-star pins, indicating their law enforcement status.

Barr asks Walters if he knows anything about Wells’ missing cattle, if he’s heard any reports. Nope, but he’ll stay on the lookout.

Barr continues to the sheriff’s office down the road. He asks the same question of the county sheriff and his deputy: Have you heard any reports of stray cattle?

He gets the same taciturn response: Nope.

After they’re done talking business, they shoot the shit. They chat about famed Texas Ranger Joaquin Jackson and the time his wife tried to shoot him while he sat on the toilet. They lament the Texas town of Marfa’s changing identity from small West Texas ranching outpost to liberal, artsy oasis. They joke about older women flashing their bare breasts at the Chilifest country music festival.

This rural social interaction is rare for a special ranger. Often, they are roaming their far-flung territories, chasing down leads, trying to catch the rustlers as an integral component in the TSCRA’s fight to protect the big business of cattle ranching, “America’s most enduring and iconic way of life,” as the TSCRA writes in its literature. They fear ranch life as it exists today could vanish. The cattle industry is under siege, according to the group, “by forces as far ranging as economic uncertainty, government regulations, crippling drought and more.”

With that kind of concern swirling in the background, the rangers are held in high regard. Special rangers serve as an added layer of insurance for ranchers, whose livelihood depends on every head of cattle they own.

Despite ranchers’ unease about the future of their industry, there are no signs that cattle ranching will disappear anytime soon. As such, cattle theft isn’t going anywhere either.

“Just as long as there’s property, there’s gonna be people out there that are gonna steal it for one reason or the other,” Gray says.