Inside the fight to save a convict’s life.

SINGAPORE—

I was sitting in a hotel room in Kuala Lumpur when I received the message on Monday afternoon. It was from Jumai, a short but heart-breaking note, sent over WhatsApp: “My brother this Friday die.”

Jumai’s brother is a 31-year-old Malaysian man named Jabing. For the past week myself and and other anti-death penalty activists have been in constant contact with Jumai, booking her and her mother flights to Singapore, picking them up at the airport, meeting in the evenings for updates and thinking of ways to get her brother off death row. I was in the Malaysian capital in the hopes of lobbying local human rights groups and politicians to act for their fellow countryman; an endeavor that yielded limited success.

It had been a long and arduous seven years for Jumai and her mother. Her brother, Jabing, was arrested in 2008 when he was 24 years old for his involvement in a robbery that led to a man’s death. Jumai’s father died of a stroke a few months later, which she attributed to health problems triggered by anxiety and worry for his son. Two years later, Jabing was convicted of murder and sentenced to death under Singapore’s mandatory death penalty regime. Under the law, anyone convicted of murder must be sentenced to death, with no chance for mitigating factors to be taken into account.

But that wasn’t the end of the family’s emotional rollercoaster. The Singapore government amended the mandatory death penalty law in 2013, allowing judges the discretion to choose between death and life imprisonment with caning—a vicious punishment in which the inmate is strapped down and whipped with a long rattan cane—for all but the most serious category of murder, as well as certain cases of drug trafficking. Jabing was eligible for re-sentencing, and a High Court judge ruled that there was “no clear evidence” he had snuck up behind his victim and hit him over the head with a piece of wood. The death sentence was set aside, replaced with a life sentence and 24 strokes of the cane.

Any relief was short-lived. The prosecution appealed the sentence, and in January 2015 the Court of Appeal—Singapore’s highest court—returned Jabing to death row in a in a 3-2 ruling. Although the two dissenting judges felt that there was insufficient evidence to determine how many times Jabing had struck his victim with the piece of wood or caused the skull fractures that led to the man’s death, the three judges in the majority believed that Jabing had showed a “blatant disregard for human life” in a way that “outraged the feelings of the community” and therefore deserved to die.

The rich Southeast Asian city-state of Singapore has long been committed to capital punishment. The death penalty was brought into law while Singapore was still a British colony, and has remained even though the United Kingdom itself abolished executions in all circumstances in 1998. Capital crimes aren’t limited to murder, but also include unlawful use of firearms and engaging in drug trafficking, with the latter making up the bulk of cases. Fifteen grams of heroin or 500 grams of cannabis can earn the offender a one-way trip to the gallows—the method of execution that Singapore has always used.

It’s a harsh position, deliberately adopted to signal Singapore’s uncompromising stance on crime. The lack of evidence that the death penalty works as a deterrent is no barrier to the government claiming that it is the threat of the noose that maintains the city’s safe, low-crime reputation.

Addressing a session of the United Nations General Assembly in September 2014, Law Minister K Shanmugam vigorously defended the use of the death penalty for drugs. “Singapore is probably either the only country, or one of the few countries in the world, which has successfully fought this drug problem,” he declared. “For those who ask for whom the death penalty can be a deterrent, I say to them, come and see for yourself in Singapore, and compare the region and the rest of the world.”

Due to the relatively low number of murder cases, discussion about the death penalty for murder is less common than the debate surrounding Singapore’s war on drugs. But the pro-death penalty rhetoric will be familiar to anyone who has ever encountered the issue: Since this person took someone else’s life, why does he deserve to live? In other words, an eye for an eye.

This narrative of retribution and punishment can also be found in the courthouse. “Although a number of jurisdictions followed the ‘rarest of the rare’ principle in deciding whether or not to impose the death penalty, this was not appropriate for Singapore,” wrote the Court of Appeal in the 2015 judgement that sent Jabing back to death row. “A more appropriate principle to adopt would be whether the actions of the offender would outrage the feelings of the community.”

All of this makes the struggle for abolition an uphill battle. Beyond a small circle of supporters there is little sympathy for people like Jabing or his family. Mercy is also in short supply; Jabing’s appeal for a presidential pardon was rejected in mid-October. It was distressing for the family, but not a surprise. The last time an inmate was granted a reprieve was in 1998.

The rejection of Jabing’s clemency appeal sparked off a flurry of activity. The most cruel of silent countdown clocks had begun to tick.

Matters have been made more complicated by the family’s limited means. Jabing comes from a poor, rural part of Sarawak in east Malaysia. His family speaks no English; his sister speaks Malay, while his mother is most comfortable in her native Iban. They flew to Singapore in 2010 to see Jabing; it took them two years to save up enough to visit him. In May we flew them back to Singapore to submit their appeal to the president for mercy, giving them another chance to see him. We flew them here again once we’d heard that the pardon had been denied.

My brother says he wants his body to be flown back to Miri

Every day, from Monday to Saturday, Jumai and her mother Lenduk would make the journey from their hostel to the imposing Changi Prison Complex in eastern Singapore to spend precious time with Jabing. They had about an hour and a half each time—treasured minutes and seconds in which they could sit and talk to him. A glass pane separated them; it’d been a long time since they’d been able to touch one another.

The night after their first visit with Jabing we sat down to dinner together in a quiet hawker center. “My brother says he wants his body to be flown back to Miri,” Jumai said. Jabing had been clear with his instructions. He’d converted from Christianity to Islam in prison, and wanted to be buried in the proper Muslim way. Fulfilling his last wish would involve the ordeal—not to mention expense—of getting a casket shipped from Singapore to Miri, then transported to the family’s rural village. He told his sister to ensure that the whole process be taken care of by the Malaysian embassy; he was worried that we Singaporean activists had done too much for him already. It was a refrain we’d heard before from inmates and their families; despite their personal anguish, they would sometimes feel embarrassed or guilty about having put activists—seen as kind-hearted strangers—to too much trouble.

It was a surreal conversation to have around a plastic table on a hazy evening—a discussion of tentative funeral plans for a young man who was not only still alive, but physically in his prime. Part of me wanted to shut down such talk; it felt too much like giving up, like accepting the execution as inevitable. Yet this was what was on Jabing’s mind, and what he had asked his sister to do.

A week passed before three police officers asked to speak to Jumai and her mother after they were done with their visitation in Singapore. The dreaded day had come. It was Monday; the officers told the family that Jabing would hang on Friday Nov. 6.

Executions in Singapore usually take place at 6 a.m. every Friday morning. Just as early-risers stir from their beds and children get ready for school, the inmate is taken from his or her cell to the execution chamber. A noose—measured out according to the individual’s weight—is placed over the prisoner’s head, the knot behind the right ear to ensure the spinal cord is snapped upon the impact of the long drop through the trapdoor. No one, apart from prison officers and doctors, is allowed to be present. From what we can gather, the process is quick, methodical, and by the book. The family is expected to claim the body by a certain stipulated time, or the state will cremate the remains.

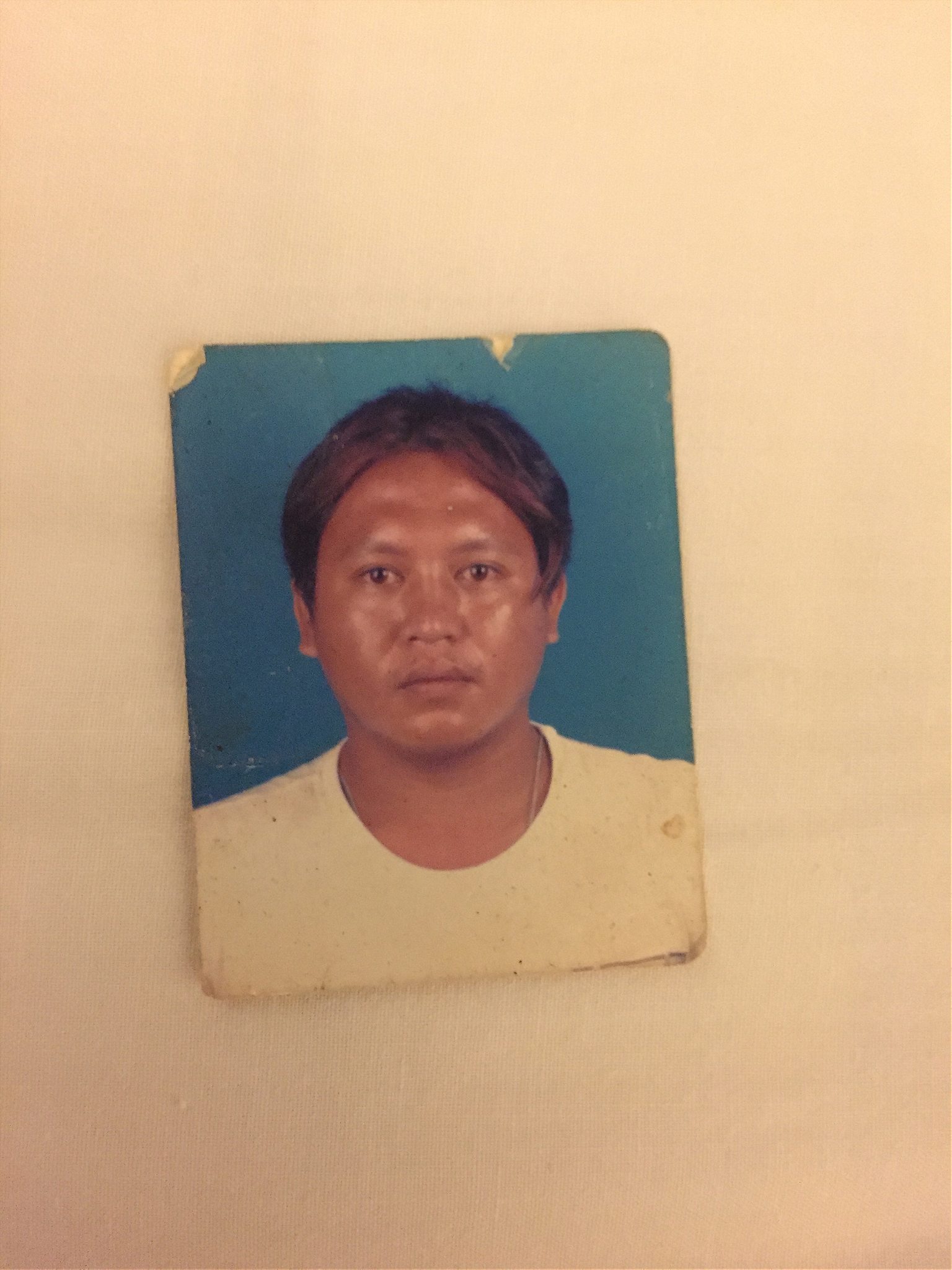

Before the execution there is a bizarre and somewhat disturbing charade. About a day or so before execution the inmate is allowed to change out of his prison uniform into regular clothes, and is made to pose for a photo shoot. The photos are then provided to the family as mementoes of their lost loved one.

It was for this shoot that Jumai and Lenduk found themselves, late on Monday night, in a sprawling 24-hour mall in Little India, looking for clothes Jabing would be able to wear. While Jumai tried to make sure that her brother would get everything he needed, Lenduk looked listlesssly at all the choices. How was she to choose, knowing that it would likely be the last set of clothes her only son would ever wear?

Both women were still reeling from the news. “If you could see my breath, you’d see it slowly disappearing,” said Jumai through a Malay translator. “I still cannot accept the fact.”

No one is willing to give up while Jabing is still alive. Yet the knowledge that time is running out and chances of a last-minute reprieve are slim is constantly at the back of all our minds, family and activists alike.

“If there is an opportunity for us to keep him alive, then at least we will have the chance to come and visit him,” Jumai said. “But sometimes I feel like all hope is lost.”

UPDATE: Kho Jabing was granted a stay of execution on Thursday, 5 November, less than 24 hours before his execution was to take place. Dressed in a purple prison jumpsuit and surrounded by prison officers, he sat in the dock as the Court of Appeal judges granted his lawyer more time to prepare the case for the criminal motion that had been filed. It is as yet unclear how long the stay of execution will last, although the court registry will soon contact all parties about setting a date for the hearing.