Photographing Afghanistan’s new middle class and the impossible reconstruction of a city.

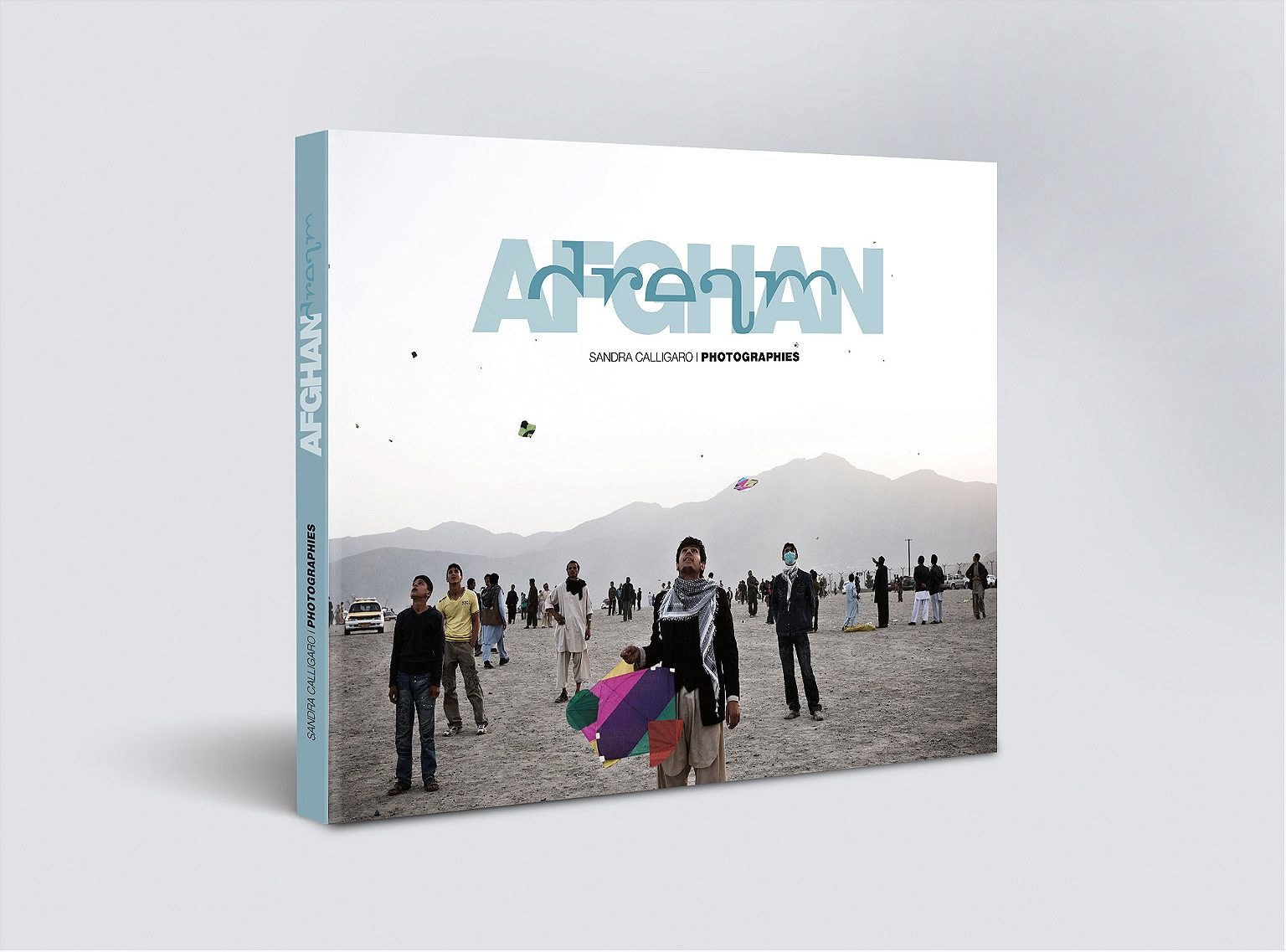

It was an ordinary day in Kabul and Sandra Calligaro, who had called the city home since 2007, decided to go shopping. She got in her car and drove to the supermarket, which is mostly frequented by expats, international workers and Afghans from the diaspora. As she walked up and down the aisles with her cart, she noticed something unusual: for the first time, there were ordinary Afghans shopping alongside her. “I asked myself, who are these people?” she explains. “This was a social class that had appeared in front of my eyes. It was the reflection of the city’s evolution.” For Calligaro, that day marked the beginning of a longterm photography project about Kabul’s middle class, a product of Western presence in Afghanistan that grew from basically zero in 2001 to about 10-15% of the country’s population today. Her upcoming book, Afghan Dream, shows her adopted city the way she talks about it with her family back home, not how it’s portrayed in much of the Western media. It shows her neighbors, her coworkers, her friends—all part of a new group of Afghans who are also part of the story of the impossible reconstruction of a city torn by a decade of conflict. She joined R&K from Paris.

R&K: When did you first visit Afghanistan?

Calligaro: It was a bit randomly actually. I studied art and photography, not journalism, but when I discovered photography I decided to become a reporter. At the end of my studies, I had a journalist friend who was supposed to return to Afghanistan to finish a documentary. I asked him to take me with him and he said no, but that I should go on my own. I didn’t know much about Afghanistan, but I left on a whim with all my preconceived ideas and my prejudices. I hadn’t planned to stay that long, just a month, and then I was hoping to go somewhere else after. But once I got there, the country amazed me. I didn’t expect to like it really, because from here we always see such a horrible image of Afghanistan. I ended up staying two months. I went back to France and quickly found an excuse to go again. After that second time, I got an assignment to go back a third time, which is when I moved there. It might sound strange, but I liked the fact that everything worked the opposite way of what I was used to and at the same time, I didn’t feel disoriented. I fit in pretty quickly and it all seemed quite natural actually.

R&K: When did you first meet the Afghans that you photographed for this book?

Calligaro: I had to go through a kind of cycle first, before meeting these people and allowing myself to think they were interesting. When I got to Afghanistan, I wanted to be a war photographer. I had to go through this quest where I put aside my artistic background and really went into news journalism. After a while, I got tired of it. I felt like I was never going deeply enough, I was always working too fast. Outside of Kabul, it’s complicated to stay long periods of time in one place. You take risks, it’s adventurous, but at the end, all the photos look alike because you can only photograph inside houses, which all start looking alike and all the stories start sounding alike too. I was frustrated on the photographic level, and even though journalistically it was interesting, I started feeling like it wasn’t working for me anymore. I had always been more interested in meeting people and taking the time to understand them, rather than doing hard news assignments. Photographing the Taliban, going to far out provinces, I did it, and then after a while I thought: OK, what do I do now?

When I started showing the project in 2012 some people laughed at me

R&K: So you turned your focus to Kabul.

Calligaro: Kabul was my city. I had my marks, my house, my two dogs, my cat, my horse, my car. In 2011, I started to photograph my city. It started with exterior shots, I showed a certain distance as opposed to the sometimes pornographic character of news photography. There was such a disconnect between the images I sent to newspapers and what I told my friends and family about Afghanistan. I wanted to show the city the way I saw it and the way I loved it. So I started with all these exterior shots, paintings almost, and after that went inside people’s homes.

R&K: Did working on this project feel more satisfying than doing hard news?

Calligaro: It’s another satisfaction. I had to own up to the fact that I was showing this image of Afghanistan. I had to feel like I knew the subject and the country well enough, that I had my own opinions and that I took responsibility for wanting to show this part of society. I am not saying that people in Afghanistan all look like this. Not at all. But they exist too and they reflect today’s country. Still, it was really difficult to communicate to editors that this wasn’t just a nice project about the rich kids of Kabul. It wasn’t a reportage that tried to say everything was going well in Afghanistan and the country was having a rebirth. No, it was more like the opposite: this is happening, these people believe in a better future, they don’t know it yet but they’re going to get a big slap in the face. That’s how I saw things when I worked on this project. And it wasn’t easy to spread that message. Some editors who saw the work even told me this wasn’t Afghanistan or they weren’t real Afghans.

R&K: Do editors still feel that way about the work today?

Calligaro: Some of them. It isn’t easy to go to something like the Prix Bayeux Calvados and show these photos. People look at me like I’m completely off-topic. I don’t think that I am. These aren’t images that you would expect from Afghanistan. In this work, I wanted to show color, restaurants, televisions, but also make a strong statement to show that people are isolated. The sky is always very low and I try to show a certain distress, a certain sadness in an other way than showing blood. Once the work became a longterm project, though, it was understood better. There isn’t any room in the press for something this big and this sociological. But I was able to get grants and exhibitions. When I started showing the project in 2012 some people laughed at me. But after a little while, I wasn’t the only one doing this anymore and people started believing that I didn’t make everything up. More and more pictures like these have started popping up from Iran, Iraq, etc. But still, I never managed to get this into a festival like Visa Pour l’Image.

R&K: Why do you think that is?

Calligaro: The photojournalism there is heavy, it’s war, it’s tears, and that’s it. Well, the world is so full of nuances and that doesn’t make any sense to me. I have a gentle relationship with Afghanistan and that’s what I’m showing. There is a Nan Goldin quote that I always think of that goes: “taking a picture is a way of touching somebody—it’s a caress.” My photography is very far from what she was doing, but this quote is what I have in mind when I work. It’s not brutal. At Visa, I think there is a more brutal vision of looking things, especially when looking at conflict zones. But I would be very proud to show my work there one day, because it can bring something different to the way we see things. Maybe next year.

R&K: How much do you think your background in fine arts and photography as opposed to journalism influenced this book?

Calligaro: It influenced the way I chose the people I photographed. I was never looking for the perfect character. It’s like the difference between reportage and documentary. In a reportage, you look for the perfect character and in documentary you look for everything else. You look for an ordinary person that represents universality, you try to focus on people who aren’t exceptional. And it’s your vision that can do that. I really worked in that direction. You won’t find photographs of Kabul’s only female rapper or of the only bicycle team in Afghanistan in this book. No, these are people that are completely ordinary.

R&K: What was your process to delve deep into this subject for such a long time?

Calligaro: The way I work is that as long as I want to go back to one story, I’m not done. It means that I don’t have all the photos I need yet. There are some young people that appear throughout the book. They are the ones who guided me. They had different ways of seeing things at different times, and that’s how I knew what I didn’t photograph enough, or didn’t make clear enough. Also, my personal point of view has changed. At first, I made a lot of photographs that were anchored in reportage, in demonstration. I’d photograph someone shopping, someone doing their homework, it was too narrative. I had to go back again and again to be able to make photographs that elevated themselves from that. So in the final selection for the book, I keep very few photos that show situations. You don’t really know what people are doing in the photos. They are a little lost. It was much more difficult to make these kinds of timeless photographs, ones that communicate feelings more than situations.

R&K: How has your view of them changed over the course of the project?

Calligaro: I thought the project was almost finished at the end of 2014. I showed some of the work at the French Institute in Kabul, but realized that what people were saying to me then was so different than when I took most of my pictures. 2013 had been a really shitty year, the elections were chaotic, and people were much less sure of the future at this point. They had grown up, too. I went back to France and a few weeks later there was an attack at the French Institute. Two people died. I didn’t know them but so many of the young people I had photographed went there regularly because it was a peaceful and cultural place. I thought, wow, if even this place is a target, what kind of youth can you really have there? I felt so guilty for not being in Kabul. It was very painful for me, this attack. And I felt the need to continue this project. I wasn’t done. It’s exactly at that point that the photographs started taking on a true heaviness. What I had feared was actually happening. People around me had changed their points of view, from wanting to go study abroad and come back, many had decided to stay abroad. I don’t blame them. Less and less of them were seeing a future in their own country.

R&K: Were you more optimistic about the future at the beginning of the project?

Calligaro: I wasn’t really optimistic, but all these people I had met had almost convinced me. Before starting the work I didn’t think that young people there had such opinions about the future. It surprised me, it made me want to believe it. I knew it wouldn’t be easy, but I just saw them being so motivated and I thought, why not? And then that was it.

R&K: What do your subjects think about the final work?

Calligaro: They like the fact that I’m not showing them like wild animals. That was also really important to me. I wanted to photograph Afghans just how I’d photograph French people or Americans if I was American. A mom who’s helping her daughter with her homework is still a mom no matter what her nationality is. I wanted the Western audience to feel close to my subjects. And this group of people resembles us. But when you really look closely, you can tell that not everything is completely normal. I’m showing normality in a country that is anything but normal. Eight years ago, I had gone to Afghanistan to photograph the extreme opposite of what I knew, but after all these years I’m coming back with work that shows all the things that bring us closer.

Sandra Calligaro’s book “Afghan Dream,” published by Pendant Ce Temps, is available here for pre-orders at a preferential price.